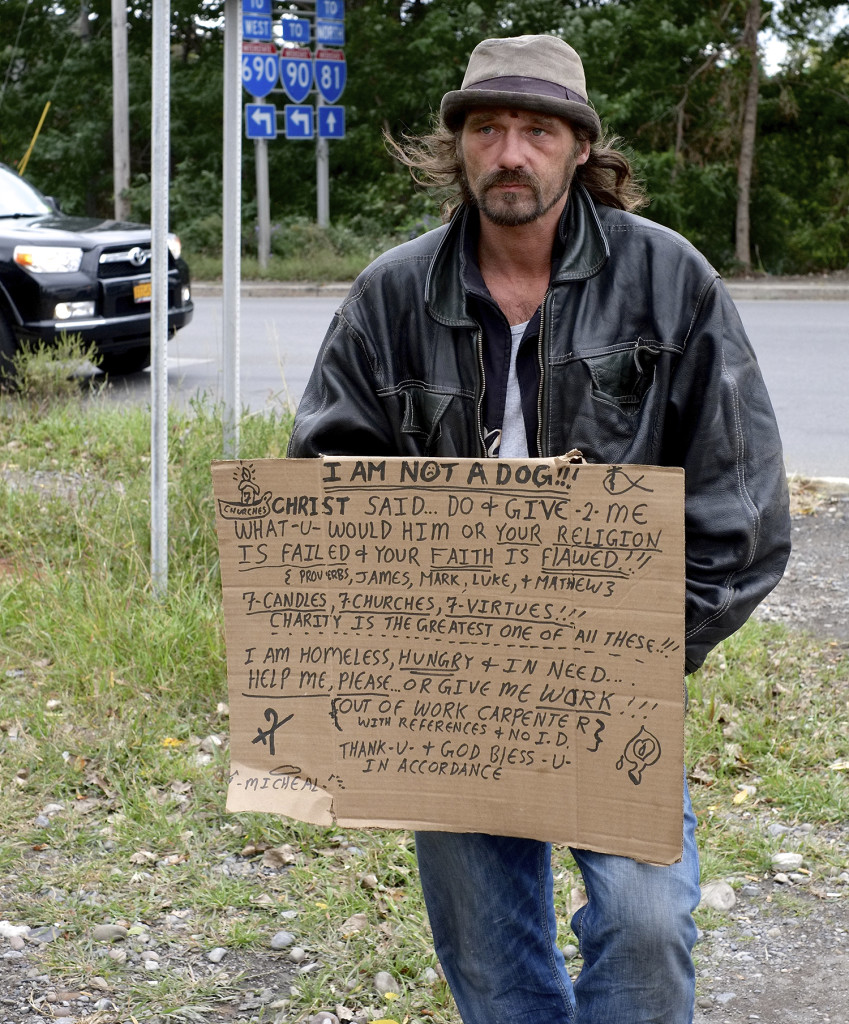

Do You See This Man? What it’s like to be homeless in Syracuse

He’s homeless, and many people pass as if he were invisible

- Michael Davis Photo | Syracuse New Times

- Michael Davis Photo | Syracuse New Times

“They’re not giving us a chance”

Micheal, 49, recalls his last interaction with a local emergency aid program: Seven months ago, he awaited his appointment with a counselor at the Rescue Mission to finish paperwork that would get him an apartment. According to Micheal, the Mission removed his name from the roster two days before the appointment because he had been at the Mission for 45 days, the maximum stay allowed. “If they would set up some housing, take us off the streets for three months, help us get our education and our IDs … Just give us a shot. They’re not giving us a chance,” he says. His voice shakes, his brow furrows. On two nights in January, a total of 851 people slept in transitional housing or emergency shelters in Syracuse and Onondaga County, and that number excludes people like Micheal who avoid shelters and aid organizations. In September, John Kuppermann, owner of Smith Restaurant Supply, sparked local interest in the issue when he complained that a homeless encampment near his store compromised the success of the business.“No one wants to be homeless. It’s circumstances of life that happened to them. Why is that so hard for people to understand?” — John Tumino, founder of In My Father’s Kitchen.Arthur Wine, one of the men who stayed at that encampment, approached Kuppermann once he saw that his few belongings at the encampment had been removed. A few weeks later, Wine lay on a cement bench at that same intersection, at North McBride and East Water streets, under a blue sleeping bag with gingham interior. “I didn’t get nothin’ back. They burnt it,” Wine says. Don Mitchel, professor of geography at Syracuse University whose research focuses on public space as it is transformed to control the behavior of the homeless, attributes the rate of homelessness in the city — and the country — to three factors: the emphasis on profit-making in housing, the dismantling of the mental health care system and the lack of fair-wage jobs for so-called “unskilled” labor. In 2013, New York’s unemployment rate rose more than any other state’s, from 5.1 percent to 8.5 percent. Visible homelessness in Syracuse extends far past one designated area. You might see a man sleeping in Syracuse University’s Walnut Park, another panhandling at South West and West Fayette streets, across from the Redhouse. You might see Micheal reading his Bible in that wicker chair on Hiawatha Boulevard or panhandling at the off-ramp, holding a sign that reads, in part, “I am not a dog!!! I am homeless, hungry + in need … help me, please … or give me work!!!”

Michael Davis | Syracuse New Times

People Doing Good Work

Homeless individuals face many constraints, but one of the most limiting is lack of transportation. Securing a job proves next to impossible when most people can’t afford $4 round-trip bus fare, says Andrew Lunetta, 25. In March 2011, Lunetta founded Pedal to Possibilities, a program geared toward homeless individuals that offers thrice-weekly bike rides. Once riders complete 10 rides, they earn their own bike, donated to the program by people in the community, bike shops and other organizations. While working at the Oxford Street Inn, Catholic Charities’ homeless shelter for men, Lunetta realized that the men had nowhere safe to go when they had to leave at 7 a.m.Lunetta obtained the Brady Faith Center as a meeting area, won a bike race, sold his prize bicycle and bought the program’s first five bikes with the cash. Individuals come to the Brady Faith Center around 7 a.m. — when many have to leave the shelter — to drink coffee, chat and read newspapers before the hour-long bike ride starts around 9 a.m. Five riders in 2011 have grown to 15 to 20 each morning.

Shawn Egnor, who joined the group in the spring, finds peace during the bike rides. “I call it freedom. It’s the freest time on my mind,” he says. Egnor, 45, who has undergone brain surgeries, rides with the group three times a week unless he has a doctor’s appointment. He used to be a car mechanic, but he lost interest in driving, and biking took over as his main form of transportation.

When Lunetta decided to pursue a master’s degree at Syracuse University a year and a half ago, he contacted Roy Durgin, who went through the program himself, to take over as program coordinator. “I’ve seen a lot of them grow. I’ve seen a lot of them get jobs and come to terms with the world, not as angry with the world as they were when I first met them,” says Durgin, who started working at a printing company on Burnet Avenue after earning his bike in 2013.Syracuse has several homeless outreach and emergency aid programs, both government and non-government-funded, for locals in need.

On a Friday in September, the Samaritan Center on Montgomery Street served 241 meals to people who can’t count on three meals a day. A few years ago the Samaritan Center, which operates on a no-questions-asked basis, served mostly homeless people. Today the center serves more families and working poor; homeless people make up one-third of the population served, says Mary Beth Frey, the organization’s executive director.

“Some of the folks we serve are just working as hard as they can and aren’t getting anywhere. People avoid them when they’re walking down the street,” Frey says. “And then there’s this place. Sometimes all it takes for someone to keep plugging is knowing that people see you.” Back on Hiawatha Boulevard, a few days after Micheal shared his story, John Tumino — founder of In My Father’s Kitchen, an organization that provides meals, support and aid to people living under and near the city’s overpasses — brought him lunch just like he has twice a week since they met in 2012. That day Tumino, the former president and operator of Asti Caffe, brought homemade meatball sandwiches. Tumino handed Asti Caffe over to his two brothers in March 2011 to found In My Father’s Kitchen, which he considered a call from God.Driving home one day, he spotted a man flying — another word for panhandling — at the I-81 off-ramp on Bear Street. People in cars all around avoided eye contact with the man. “I felt in my heart, ‘He thinks he’s invisible,’” Tumino says. He drove to Wegmans; bought a sandwich, water bottle and dessert; parked his car near Bear Street; and brought the meal to the man, Tim. And that one lunch, that one guy, resulted in In My Father’s Kitchen.

Since then, Tumino has served thousands of lunches to more than 200 homeless people.

Tumino contends, homelessness is not a choice. Pain, struggle, and challenges put people in that place. “No one wants to be homeless. It’s circumstances of life that happened to them. Why is that so hard for people to understand?” One year ago, Tumino organized a funeral for Mark, a homeless friend of his who died in a fire in an abandoned home on Lynch Street while trying to keep warm. “I got to see the baby pictures, when he was a kid, a beautiful blond-headed boy. And I’m like, ‘What happened? When did it happen? What was the trigger that started the cycle?’ Because I see this boy at 9 riding his bike with his blond head of hair and the sky’s the limit,” he says. Tumino calls In My Father’s Kitchen “the bridge out from under the bridge.” In September 2012, a year after he began making lunches and building relationships with the people at off-ramps and under bridges, Tumino started helping his friends — not clients — like Micheal and Tim “come indoors.” Tumino bridges the gap between the homeless individuals and organizations like the Salvation Army and Catholic Charities that help them obtain identification, Supplemental Security Income and an apartment. Since that September, Tumino has helped 16 of his friends get off the streets. One of these men was Micheal, but within a year of moving in, he broke the rules set in place by his landlord and was evicted. “If you don’t deal with the core addiction, you can get housed, cleaned up, on food stamps, and you’ll lose it all,” Tumino says.