With the recent focus on homelessness in Syracuse, some media organizations asked people what they thought of panhandlers. Syracuse New Times reporter Michelle Malia van Dalen asked homeless people about their lives in Syracuse.

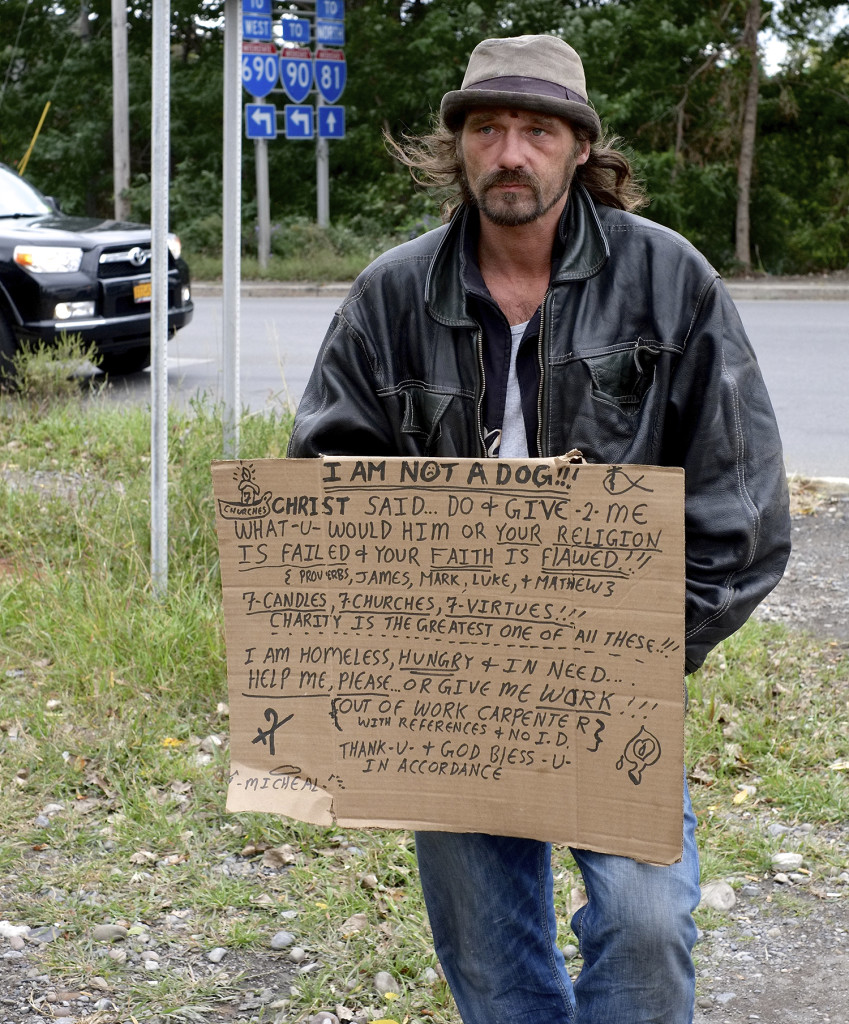

Under the Interstate 690 overpass on Hiawatha Boulevard, Micheal sits with his back to the street in a disintegrating beige wicker chair flanked by two cement pillars. Old newspapers are strewn around his sneaker-clad feet. He wears a leather jacket and faded blue jeans, and his hair creeps past his shoulders, emerging from under a brown fedora. The constant din of passing traffic muffles his words, but he raises his voice over the sound. “Many of us are abandoned out here. We don’t have no parents ’cause they didn’t want us. They wanted a baby, they had a baby, they threw the baby away. It’s not my fault,” says Micheal, who chose to withhold his last name.

Micheal is not alone on the streets. Every day men and women stand on street corners, passing the time under bridges and hang out near intersections until they can sleep or return to whichever homeless shelter they call home.

Organizations across the city seek to help homeless people, offering them company, food, housing and other support. Together, homeless people and organizations create their own community, one of respect and resentment, acceptance and denial, addiction and recovery.

It depends on the person, and it depends on the day.

“They’re not giving us a chance”

Micheal, 49, recalls his last interaction with a local emergency aid program: Seven months ago, he awaited his appointment with a counselor at the Rescue Mission to finish paperwork that would get him an apartment.

According to Micheal, the Mission removed his name from the roster two days before the appointment because he had been at the Mission for 45 days, the maximum stay allowed. “If they would set up some housing, take us off the streets for three months, help us get our education and our IDs … Just give us a shot. They’re not giving us a chance,” he says. His voice shakes, his brow furrows.

On two nights in January, a total of 851 people slept in transitional housing or emergency shelters in Syracuse and Onondaga County, and that number excludes people like Micheal who avoid shelters and aid organizations.

In September, John Kuppermann, owner of Smith Restaurant Supply, sparked local interest in the issue when he complained that a homeless encampment near his store compromised the success of the business.

“No one wants to be homeless. It’s circumstances of life that happened to them. Why is that so hard for people to understand?” — John Tumino, founder of In My Father’s Kitchen.

Arthur Wine, one of the men who stayed at that encampment, approached Kuppermann once he saw that his few belongings at the encampment had been removed. A few weeks later, Wine lay on a cement bench at that same intersection, at North McBride and East Water streets, under a blue sleeping bag with gingham interior. “I didn’t get nothin’ back. They burnt it,” Wine says.

Don Mitchel, professor of geography at Syracuse University whose research focuses on public space as it is transformed to control the behavior of the homeless, attributes the rate of homelessness in the city — and the country — to three factors: the emphasis on profit-making in housing, the dismantling of the mental health care system and the lack of fair-wage jobs for so-called “unskilled” labor.

In 2013, New York’s unemployment rate rose more than any other state’s, from 5.1 percent to 8.5 percent. Visible homelessness in Syracuse extends far past one designated area. You might see a man sleeping in Syracuse University’s Walnut Park, another panhandling at South West and West Fayette streets, across from the Redhouse.

You might see Micheal reading his Bible in that wicker chair on Hiawatha Boulevard or panhandling at the off-ramp, holding a sign that reads, in part, “I am not a dog!!! I am homeless, hungry + in need … help me, please … or give me work!!!”

Mitchel says: “People internalize and say they’ve made bad choices. But think about the world within which those bad choices are made. My world is not constrained like that. The constraints of poverty, bad education and lack of health care limit the kinds of choices you can make.”

People Doing Good Work

Homeless individuals face many constraints, but one of the most limiting is lack of transportation.

Securing a job proves next to impossible when most people can’t afford $4 round-trip bus fare, says Andrew Lunetta, 25.

In March 2011, Lunetta founded Pedal to Possibilities, a program geared toward homeless individuals that offers thrice-weekly bike rides. Once riders complete 10 rides, they earn their own bike, donated to the program by people in the community, bike shops and other organizations.

While working at the Oxford Street Inn, Catholic Charities’ homeless shelter for men, Lunetta realized that the men had nowhere safe to go when they had to leave at 7 a.m.

Lunetta obtained the Brady Faith Center as a meeting area, won a bike race, sold his prize bicycle and bought the program’s first five bikes with the cash. Individuals come to the Brady Faith Center around 7 a.m. — when many have to leave the shelter — to drink coffee, chat and read newspapers before the hour-long bike ride starts around 9 a.m. Five riders in 2011 have grown to 15 to 20 each morning.

Shawn Egnor, who joined the group in the spring, finds peace during the bike rides. “I call it freedom. It’s the freest time on my mind,” he says. Egnor, 45, who has undergone brain surgeries, rides with the group three times a week unless he has a doctor’s appointment. He used to be a car mechanic, but he lost interest in driving, and biking took over as his main form of transportation.

When Lunetta decided to pursue a master’s degree at Syracuse University a year and a half ago, he contacted Roy Durgin, who went through the program himself, to take over as program coordinator. “I’ve seen a lot of them grow. I’ve seen a lot of them get jobs and come to terms with the world, not as angry with the world as they were when I first met them,” says Durgin, who started working at a printing company on Burnet Avenue after earning his bike in 2013.

Syracuse has several homeless outreach and emergency aid programs, both government and non-government-funded, for locals in need.

On a Friday in September, the Samaritan Center on Montgomery Street served 241 meals to people who can’t count on three meals a day. A few years ago the Samaritan Center, which operates on a no-questions-asked basis, served mostly homeless people. Today the center serves more families and working poor; homeless people make up one-third of the population served, says Mary Beth Frey, the organization’s executive director.

“Some of the folks we serve are just working as hard as they can and aren’t getting anywhere. People avoid them when they’re walking down the street,” Frey says. “And then there’s this place. Sometimes all it takes for someone to keep plugging is knowing that people see you.”

Back on Hiawatha Boulevard, a few days after Micheal shared his story, John Tumino — founder of In My Father’s Kitchen, an organization that provides meals, support and aid to people living under and near the city’s overpasses — brought him lunch just like he has twice a week since they met in 2012. That day Tumino, the former president and operator of Asti Caffe, brought homemade meatball sandwiches.

Tumino handed Asti Caffe over to his two brothers in March 2011 to found In My Father’s Kitchen, which he considered a call from God.

Driving home one day, he spotted a man flying — another word for panhandling — at the I-81 off-ramp on Bear Street. People in cars all around avoided eye contact with the man. “I felt in my heart, ‘He thinks he’s invisible,’” Tumino says. He drove to Wegmans; bought a sandwich, water bottle and dessert; parked his car near Bear Street; and brought the meal to the man, Tim. And that one lunch, that one guy, resulted in In My Father’s Kitchen.

Since then, Tumino has served thousands of lunches to more than 200 homeless people.

Tumino contends, homelessness is not a choice. Pain, struggle, and challenges put people in that place. “No one wants to be homeless. It’s circumstances of life that happened to them. Why is that so hard for people to understand?”

One year ago, Tumino organized a funeral for Mark, a homeless friend of his who died in a fire in an abandoned home on Lynch Street while trying to keep warm. “I got to see the baby pictures, when he was a kid, a beautiful blond-headed boy. And I’m like, ‘What happened? When did it happen? What was the trigger that started the cycle?’ Because I see this boy at 9 riding his bike with his blond head of hair and the sky’s the limit,” he says.

Tumino calls In My Father’s Kitchen “the bridge out from under the bridge.” In September 2012, a year after he began making lunches and building relationships with the people at off-ramps and under bridges, Tumino started helping his friends — not clients — like Micheal and Tim “come indoors.”

Tumino bridges the gap between the homeless individuals and organizations like the Salvation Army and Catholic Charities that help them obtain identification, Supplemental Security Income and an apartment. Since that September, Tumino has helped 16 of his friends get off the streets. One of these men was Micheal, but within a year of moving in, he broke the rules set in place by his landlord and was evicted. “If you don’t deal with the core addiction, you can get housed, cleaned up, on food stamps, and you’ll lose it all,” Tumino says.

The Struggle of Change

“There are beautiful people out there on the street,” says John Eberle, who worked at the Rescue Mission for 14 years and serves as vice president of grants and community initiatives at the Central New York Community Foundation. “They are amazing, and they all have a story. They’re all someone’s son, daughter, dad, mother, sister, or brother. They’re people, and they’re all beautiful in their own right.”

Eberle stresses that the homeless individual must want to get off the streets for a successful transition into an apartment.

“People want to make their own choices, and that’s understandable. It’s really sad to see people who seem stuck in a bad or angered situation who don’t want the help,” Eberle says. “But if people are making their own decisions, it’s out of the control of community organizations and service providers.”

After Kuppermann made his complaints public, Tumino and Catholic Charities arranged an apartment for the four men sleeping at the intersection. And Wine, whose belongings were taken from the encampment by the Syracuse Department of Public Works, exemplifies exactly this: an independent man who goes it alone. Of the four men, Wine was the only one to turn down the apartment.

He still sleeps in that blue sleeping bag on the cement bench where East Water Street meets North McBride Street. “They tried to take me to an apartment, but I told John, ‘The dump I just came from is cleaner than this dump. Take me back there.’ They think because you’re homeless you’ll accept anything,” says Wine, who has cancer and coughs up blood regularly but refuses medical help.

Where will he sleep when the weather turns cold? “Hopefully I won’t have to worry about it,” Wine says. He expects to die before then.

While some people turn down help, others lose their access to it.

During that Friday mealtime at the Samaritan Center in September, a fight broke out between a man and a woman with a baby in her arms. As soon as the open-palm hurling, fist swinging and yelling grabbed everyone’s attention, one frequent volunteer – a man who works in the justice system – instinctively dropped the tray he was drying, rushed to the fight and helped calm the situation.

“They’re kicked out for good,” Frey says.

The volunteer brought up some security measures he hopes the Samaritan Center will implement at its future location in the former St. John the Evangelist Church, on North State Street. One of these measures: swapping out the loose tables and chairs with cafeteria-style seating, where the chairs are attached to the tables; a few weeks earlier, a man swung a chair at Steve during a meal.

The Samaritan Center recently banned another man, Sylvester Vazquez. On the morning after a rainy night in September, Vazquez, 39, sat on a cement bench — the same bench where Wine sleeps — with Leroy Weeks, 34. The sky was overcast and the concrete damp. A thin, twin-sized mattress lay on the ground a few feet in front of the bench, a pillow and sleeping bag scattered across it.

Vazquez’s curly, disheveled, dark gray hair buried much of the red and yellow bandana wrapped around his head. In October 2005, he was charged with first-degree sexual abuse, a felony. He sleeps at the Oxford Street Inn, which they dub “The Ox.” Weeks was kicked out of The Ox and sleeps on that light blue floral mattress that lies on the ground five feet in front of him. Vazquez used to get meals at the Samaritan Center, but he says he was kicked out after he pulled a knife.

“We create a space where people feel respected,” Frey says. “There are real expectations of behavior that we enforce because this needs to be a place where people are safe, a place where people can feel comfortable in an otherwise unstable world.”

Liddy Hintz is director of Emergency & Child Welfare Services at the Salvation Army, a branch that includes a 60-bed family shelter, which over the past two years has primarily served families with children, and a 15-bed women’s shelter, which serves women with mental health issues. Both shelters help people during times of temporary homelessness.

Almost 98 percent of New York’s emergency shelter beds were used in 2013. Since the Salvation Army began providing its clients with housing case managers in spring 2008, the recidivism rate has dropped. It served about 300 families a year; now the shelter serves more than 400 because they can house clients quicker.

Hintz sees the mental and emotional effects, not always violent, of poverty and strain in some of the individuals who pass through there. She recalls one woman who came to the shelter with her four children after suffering a miscarriage. The trauma of the event sent her into an emotionally dark place, and in combination with other factors, sent her and her children into temporary homelessness. At the beginning of the family’s month-long stay, the children ran in and out of Hintz’s office daily, writing on her whiteboard, saying “Hi” to the Cookie Monster she keeps under her desk, craving attention. The mother’s overwhelming emotion closed her off from her kids. Toward the end of the family’s stay, Hintz noticed a lightness in the mother’s step and a calmness in the children. She had opened up and could better give her children attention and affection. “She told me what really helped her to move on was having someone who she could talk to when she was here, someone to support her and help her through the difficult times,” Hintz says.

Others understand the emotional struggle and the need for an outlet during tough times. When Ted Bauer experienced difficulty readjusting after being in the Army from 1982 to 1992, he found that biking helped him with his anger and depression. Bauer, 48, has biked across the country four times and started riding with Pedal to Possibilities in 2011.

A whiteboard at the Brady Faith Center’s entrance shows that he tops the chart with 341 bike rides with the program. “Maybe I’m being mystical about it, but I think there’s more to it than just physical exercise,” Bauer says. “I kind of look at it like a form of meditation.” A new rider shows up to Pedal to Possibilities every week and Tumino, whose ultimate goal is to get his friends like Micheal indoors, sees a new face a few times a year.

“All we can do is just continually encourage them and bring them to the water. We can’t make them drink it, but we just always lovingly encourage them,” Tumino says.