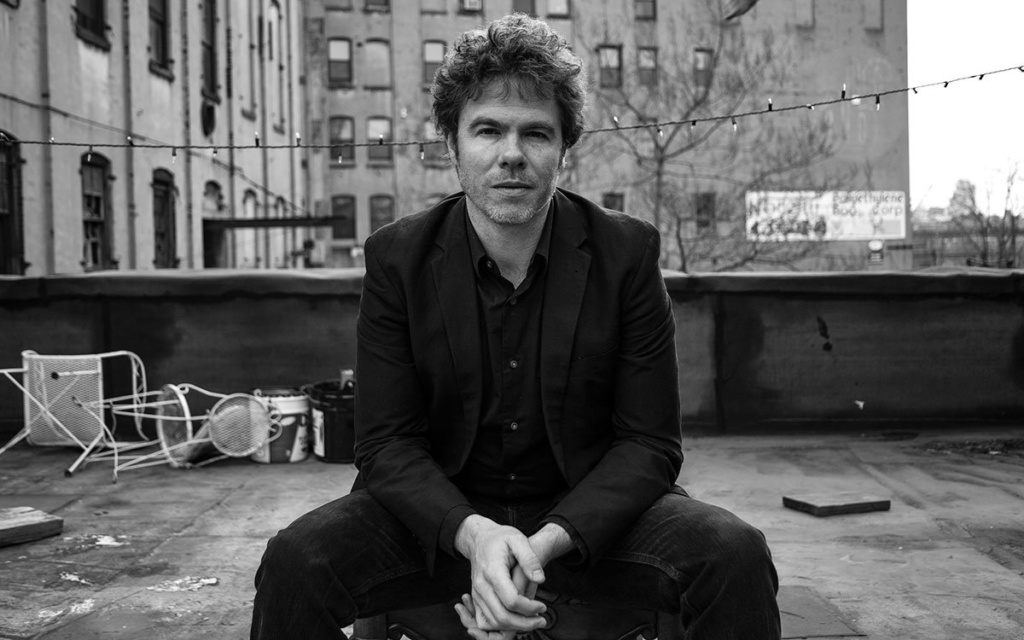

Following in the footsteps of songwriter-storytellers like Bob Dylan or Johnny Cash, Josh Ritter doesn’t just sing songs of clichés or wandering words. He tells stories through the characters in his tunes, weaving tales both real and imagined to teach lessons and connect listeners.

He’ll bring his tuneful show to Ithaca’s Hangar Theatre, 801 Taughannock Blvd., on Tuesday, Nov. 7, 8 p.m., where he’ll perform songs from his latest album, Gathering, released in September, with the Royal City Band. Tickets are $40; call (877) 987-6487 for information.

Ritter took a few minutes while on tour to speak with the Syracuse New Times about where he finds the stories for his songs, bringing his family on the road and turning dissatisfaction into an asset.

Tell me about your start in music.

I started around 20 years ago when I was 17. I just picked up a guitar and started writing songs out of the blue. I had played the violin, but couldn’t note read and wasn’t stellar at it. I discovered guitar and writing songs and it’s all I’ve wanted to do ever since. Since that moment, it’s been a journey of trying to make that my life.

You have a distinct storytelling style. Did that come from your early influences?

Early on, I was influenced by the traditional ones: Woody Guthrie or Johnny Cash. But there was also lots of Lucinda Williams, Gillian Welch, all kinds. And it’s so rarely purely musical. Influence comes from the books you read, your childhood. Oftentimes when naming off your list of influences, it’s like giving a recipe.

Where do the characters in your songs come from, such as in “The Curse”?

The characters come out of the blue. You sit down when you’re feeling it: You’ve got a place to write, pen, paper, your guitar, and something like “The Curse” just happens by magic. There is something there; a first line will unlock a whole world. And I didn’t know what was going to happen to the characters until the end.

I think about it like you’re in your own living room in the dark. You’re stumbling, looking for the light switch, you turn it on, and the whole song becomes illuminated. When I perform, the lyrics are muscle memory. The story is what I follow. It’s a mystery at the core.

You have a daughter, Beatrix. How has being a father changed you as an artist?

Big ways! In the very physical sense, having a kid can constrain your time. You’re not allowed to sit around and write for 12 hours anymore. You have things to do. You’re always getting your kid somewhere, changing a diaper, something. You have to take your writing from the desk and into your head. Writing goes weird at that point. You can’t always write it down. You have to carry it around in your mind. Your ideas get more polished.

And you travel with her?

She and my wife are on the road with me right now. Since B was born they’ve been on the road with me. It’s cool in a macro sense. You notice all kinds of things. It’s a special thing to be with someone who sees snow for the first time.

She’ll soon be 5 and we get home the day before her birthday. Since she was 3 months old, she’s been on almost every tour. She’s been all over Europe and the United States. And I keep promising the band we’ll go to Japan.

I’m incredibly lucky. It’s really special. And it’s nice that I’ve got a really great band and a great crew. We’re a real big family.

You’ve been writing songs for a long time. How do you keep going?

Writing: It’s one of the things I realized with this record. I had to make friends with the part of me that’s unsatisfied. The trap of satisfaction is real. I’m never completely satisfied with my work and it’s a blessing and a curse. The dissatisfaction is what makes me what I am. I never get offstage and am like, ‘That sucked. We can do better.’ It’s more like, I want to see what else is out there. I’ve been me for a long time. I want to try and be a different me on stage. It’s evolution, but more of a determination. I think of songs like medicine: They make you feel better in a certain way. I want my music to do that. That’s what it’s all about. Being at peace with the dissatisfaction is important for my own brain and life.

You mention this record being important to that process of understanding the dissatisfaction. How so?

This record was my first time waking up to that part of my own psyche. You’re taught as a writer that an editor is bad. The editor isn’t bad. The editor is the soul, the part that takes the unformed stuff and turns it into something usable. The editor is my best friend, not my worst enemy. If I keep trying to distance myself from that side, things lose their spark. That’s what I really discovered with Gathering. Be friends with that editor.

You wrote a novel in 2011, Bright’s Passage. How does it relate to writing songs?

Every word needs to have a function. That’s the thing. They need to have real stamina. I have such respect for novelists. I wrote 1,000 words a day every day for a couple months and I was done. Then the hard work started, getting the marble together to make the sculpture.

What advice do you have for musicians who want to do what you do?

It’s all a matter of knowing that what you’re doing is profoundly important these days. It’s so important to know that music is out there and it’s a form of connecting with human beings on the most elemental level. What we need right now is connection in our lives. It matters beyond anything that happens in a career. It’s like water to our lives. Be super-proud of doing it. Everything else is on top. Although it allows me to have my lifestyle with my family, all of that is lucky to be there, but making the human connection is the honor.[snt]