The Walter Gross-Jack Lawrence hit “Tenderly” was released seven years before the youthful Rosemary Clooney recorded it in 1952. Audiences who remember Clooney (1927-2002) might more readily cite as signature tunes the wistful “Hey, There” or the countryish “This Ole House.”

But Janet Yates Vogt and Mark Friedman knew what they were doing when they chose Tenderly as the title for their jukebox biography. Outwardly Clooney might have looked like a less tomboyish Doris Day, but inwardly she was a wounded butterfly, a blond Judy Garland who pulled through. Tenderly continues the 2016 season at Auburn’s Merry-Go-Round Playhouse, running through Oct. 19.

Don’t feel culturally deficient if you did not know there was a musical about Rosemary Clooney or had not heard of its creators Janet Yates Vogt and Mark Friedman. Although they appear to be under 40 years old, Vogt and Friedman have been prolific, with many shows aimed at younger audiences, such as How I Became a Pirate.

Perhaps because they were not around when Clooney’s songs were on TV’s Your Hit Parade, their Tenderly goes light on nostalgia. We never hear a complete rendition of “Come On-A My House,” an Americanized Armenian folk song, because Clooney hated it and often refused requests. (The script also answers the question on the minds of many in the audience: Indeed, she was the aunt of movie star George Clooney.)

Vogt and Friedman developed Tenderly at Dayton’s Human Race Theatre Company. It subsequently enjoyed a sold-out run at Cincinnati’s Playhouse in the Park, across the river from Maysville, Ky., where Clooney was born. National attention has been on the rise more recently; Tenderly is a regional premiere, with director Douglas Hall in charge of the MGR mounting.

Action begins when Clooney (incarnated by Jennifer Swiderski in a period blond wig) was past her prime. She collapses at Harold’s Club in Reno, right after delivering an affecting “Hey There.” A series of gunshots punctuate the gloom. We soon learn that she thought she heard the shots from the assassination of Bobby Kennedy, with whom she had been close. The year is 1968, but she had been nowhere near the crime.

In the next scene Clooney is at Cedars-Sinai Hospital in Beverly Hills, talking to an impassive psychiatrist (Scott Guthrie). She’s not a pretty patient. As a celebrity, she flouts the prohibition on smoking, mocks the interview (“What! No couch?”), and is in denial. She doesn’t think there is any problem and will not open up, despite her being a mess professionally, unable to continue to perform.

Whether or not this is actually what happened is immaterial. Vogt and Friedman recognize that most audiences knew little of her darker side. It has to be dug out.

Clooney achieved success early, had a generally sunny public personality and enjoyed a long career, still pulling in paying crowds in her last years. She suffered a bit of a dip when Elvis Presley appeared, however, and she represented the opposite of what rock’n’roll is, but that was not the problem.

Along with the kind of insecurity that plagues many come-from-nowhere performers, and the early death of her beloved sister Betty, Clooney was knocked off the rails by her failed marriage to a horrible egotist. Jose (“Joe”) Ferrer, the golden-voiced Oscar winner (for Cyrano de Bergerac) was a shameless philanderer and not much fun to be around, even though he fathered five children. Later in life Clooney found happiness with a dancer named Dante DiPaoli, whom Vogt and Friedman link to her hit song, “Mambo Italiano.”

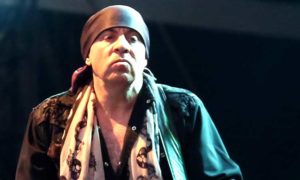

The psychiatrist, Ferrer, DiPaoli and nine other people of different ages and ethnicities are all played by Scott Guthrie, without a costume change. These include some of the top performers of the time, most of whom considered Clooney to be a peer. Guthrie’s take on Frank Sinatra is helped along by a scarf and a hat, but his Bing Crosby is spot-on. Good thing, too, because Crosby not only co-starred in Clooney’s best movie, White Christmas (1954), but also reached out to her when she hit bottom.

A tall, attractive woman with a fairly narrow face, Jennifer Swiderski gracefully evokes Clooney, whose image is less familiar than her sound. She is in command of the idiom and phrasing of Clooney’s delivery, and her handling of nearly 20 numbers should warm the hearts of audiences who came of age in the Eisenhower presidency. The extensive portrayal of her offstage angst never diminishes the beauty of her legacy.