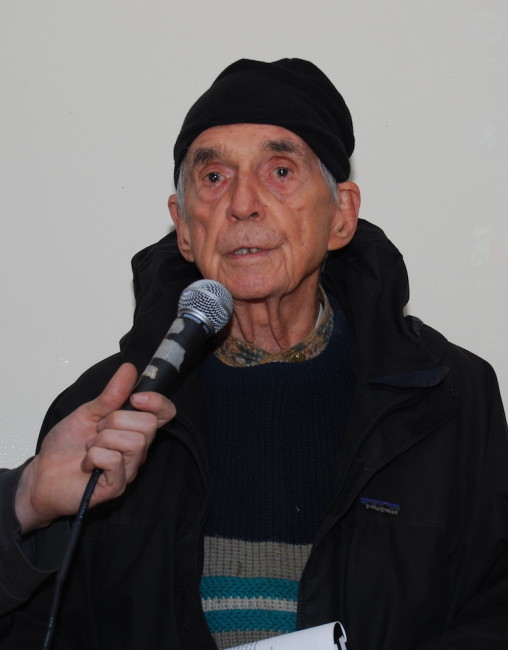

Since infamous Jesuit activist Daniel Berrigan died April 30, tributes have exploded, praising the influence the “holy outlaw” had on the peace movement and the Catholic Church. He’s been lauded as one of the most influential modern Catholic thinkers. Although the priest died just nine days short of his 95th birthday, many have mourned the end of a certain kind of activism, unyielding in its commitment to seeking a peaceful world based on principles of faith.

My brush with Berrigan fame came in 1984. He had just spoken to about 120 people at Le Moyne College, where he taught for six years before his anti-war activism brought him international fame.

I was a college sophomore. David Bowie’s “Let’s Dance” was a big hit, and Prince had yet to release his film Purple Rain. Ronald Reagan was in the White House, and when people mentioned Star Wars, they were often talking about the escalating nuclear arms race with Russia.

Berrigan, the priest and poet known for the 1968 Catonsville, Md., protest in which he and eight others set draft records afire with homemade napalm, was on campus to deliver the provocatively titled lecture “The Disarmed Christ and the Deterring Church.” Berrigan, ever austere with spirituality leaning to self-righteousness, blasted Reagan’s warmongering and criticized Catholic bishops for not strongly enough opposing Reagan’s policies. Disarmament, he said, is “a powerful statement of piety.”

It was the kind of blunt statement that made Berrigan a hero, an inspiration and role model to some and a traitor with questionable Christian credentials to others. It was, without question, heady stuff for impressionable students at a small Catholic college in upstate New York.

The existence of nuclear weapons, he continued, raises the question: “What does our God look like?”

God “looks like … what we look like to one another,” he answered. God is in “how we see women, and blacks, and Native Americans, and children and the aged, and the expendable of our great cities, and El Salvadorans and Nicaraguans. If the question is truly understood, it opens up every question.”

Boom. In one quote, Berrigan challenged every Catholic — no, every human being — to consider his convictions: Every life has value. You can’t say you love people and destroy them. If you say everyone is made in the image of God, you must love everyone, because everyone is connected.

Berrigan, then 63, joined a handful of students for a beer after that lecture. As I recorded in an earnest article for a Le Moyne College literary magazine, Berrigan asked us about our studies and our plans for the future. (Alas, my story includes no direct quotes from that conversation.) He spent less than an hour with us, but memories of that encounter have stayed with me.

Soon after news of his death became public, family and friends were describing their own encounters with Dan and his activist brothers, Philip, who died in 2002, and Jerry, who died last summer.

Dan attended Jerry’s funeral at Syracuse’s St. Lucy’s Church in July. The sole surviving Berrigan brother — frail, stoic and silent — sat in a wheelchair next to his brother’s coffin. Dan didn’t speak during the funeral — an ironic metaphor that could not have escaped the lifelong poet.

Everyone, it seems, has a Berrigan story. A colleague noted that generations of Onondaga Community College students who took Jerry’s English class read The Trial of the Catonsville Nine, a play Dan wrote based on trial transcripts. A college friend posted on Facebook that Berrigan had befriended and influenced her parents — especially her father, a young poet and playwright — while he taught theology at Le Moyne.

He inspired one friend to think about whether the stores she shops and how she invests her money are ethical. More friends than I can count attribute their careers as chaplains, clergy, health care workers, social workers and the like to Berrigan’s influence.

Not everyone is a Berrigan fan, of course. The Rev. Frank Haig, who was president of Le Moyne in the 1980s, called Berrigan “an enfant terrible.” That’s what he told me when I asked him why he hadn’t attended the Le Moyne speech by his brother Jesuit.

Haig, the Jesuit priest, missed Berrigan’s 1984 campus speech because he was in New York City to hear his brother, Alexander Haig, give a speech on his book Caveat: Realism, Reagan Foreign Policy (Scribner, 1984). Rev. Haig’s rebuke was likely a reference to Berrigan’s criticism of the Reagan administration’s role in the nuclear arms race. Alexander Haig, who had served as secretary of state under Reagan, once famously said a “nuclear warning shot” in Europe might deter the Soviets.

Is it any surprise that Berrigan would find Haig’s comment unacceptable — especially from a Catholic?

“In my part of the insular and idiosyncratic Catholic world in the 1960s and 1970s, the Berrigans were considered so far beyond the mainstream as to be freaks, and irrelevant,” another friend explained in an email. “Most of the Catholics in my circle thought Dan Berrigan’s relation to the peace movement was like Abbie Hoffman’s to the peace movement: pretty much over the top, and completely absurd.”

After reading the work of the influential Catholic writers Thomas Merton and Henry Nouwen, he “realized the true meaning of the Berrigans and their devotion to peace and justice.”

More than one person shared my experience as middle- and working-class kids whose families considered Berrigan a criminal and a bad influence. One friend said that her family’s disapproval spurred her interest in connecting with Dan Berrigan when she arrived at Le Moyne.

Another friend, who encountered Berrigan at anti-war protests in the 1960s, contrasted the Jesuit priest bearing witness against the Vietnam War with the activist’s star quality. “I was immediately drawn by his intensity, his focus, his charisma,” my friend wrote. “He was a star, right up there with Gore Vidal and Norman Mailer and Howard Zinn and Benjamin Spock. Even then I recognized his enormous ego: He was, I think, at least 49 percent about himself; certainly he had no room for intimates of either gender. He was very handsome, and no doubt attracted many admirers.”

He called Berrigan “at best a flawed saint. They disappoint me, but they inspire me, too.”

What to make of the influence of this radical priest, who grew up in Syracuse in a modest but devout Catholic home? Why the outsized influence among Central New Yorkers that belies the relatively short time he spent here as an adult?

It may be, in part, the lofty company Berrigan kept. This was a guy who hung out with moral giants like Dorothy Day, Thomas Merton, the Buddhist monk Thích Nhất Hạnh and the leftist historian Howard Zinn.

He crossed into the pop culture world as “the radical priest” in Paul Simon’s 1972 song “Me and Julio Down by the Schoolyard.” He had a brief cameo role in The Mission, the 1986 movie about Jesuit missionary efforts in South America. In one uncharacteristically commercial venture, he posed for a 1994 Ben & Jerry’s ad, holding a bowl of mocha fudge ice cream as if it were a chalice.

With his brother Philip, then also a priest, Dan Berrigan both shocked and mesmerized the Catholic world with the 1968 Catonsville protest. The enduring image of priests in clerical collars burning draft records caused a sort of cognitive dissonance. Where’s the line between clergy and activist, between church and state, between American and Christian? And why are priests who grew up in upstate New York in the middle of these debates?

But Berrigan expressed no doubt. “Know where you stand and stand there,” he once said, in what is reportedly the full text of a commencement speech he gave.

Berrigan maintained his opposition to war by criticizing American intervention in Central America, the Gulf War in 1991, the Kosovo War, the U.S. invasion of Afghanistan, and the 2003 invasion of Iraq. People who met with him at the end of his life said he was concerned about the use of drones in war.

In 2012 he was at New York City’s Zuccotti Park to protest charges against Occupy Wall Street activists. “Our task is not to be popular or to be seen as having an impact, but to speak the deepest truths that we know,” Berrigan told Chris Hedges, a Colgate University graduate and former New York Times correspondent who wrote War Is a Force that Gives Us Meaning (PublicAffairs, 2002). “We need to live our lives in accord with the deepest truths we know, even if doing so does not produce immediate results in the world.”

The day Berrigan died, I posted on social media a picture of the 1971 Time magazine cover featuring a story called “Rebel Priests: The Curious Case of the Berrigans.”

“Then there were none,” I wrote. “Not none,” a friend quickly responded. “Just us.”

Renée K. Gadoua is a freelance writer and editor. Follow her on Twitter @ReneeKGadoua.