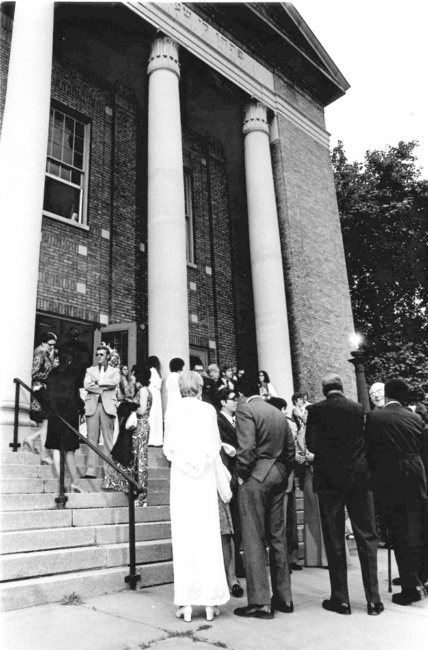

The splendid edifice at 601 S. Crouse Ave., now known as the upscale Hotel Skyler, gives little hint of its storied history. From 1916 until the early 1970s it was the home of Temple Adath Yeshurun, now decamped to Kimber Road, DeWitt.

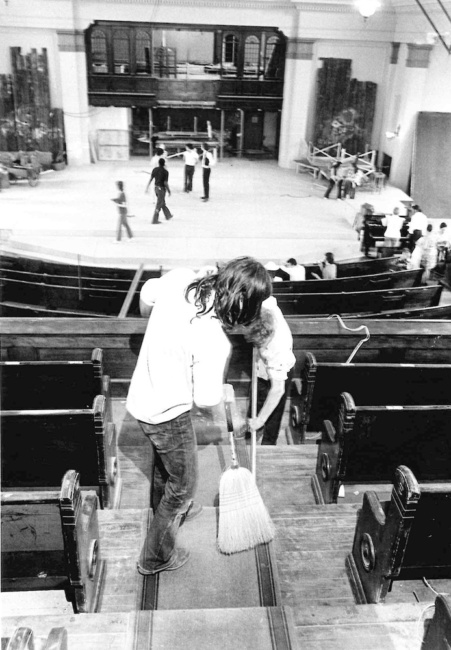

For the 30-plus years between the temple and 2004, however, the imposing columns of architect Gordon Almond Wright’s Greco-Roman façade enclosed a scrappy, short-on-funds artistic company known grandly as the Salt City Center for the Performing Arts, or, more familiarly, Salt City Playhouse.

Drawing on interviews with key players, Russell Fox’s new book, The Salt City Playhouse: An Itinerance, 1978-1981 (Bloomington, Ind.: iUniverse, 2015. 316 pages; softcover. ISBN: 978-1-4917-7965), gives extensive details on limited aspects of the enterprise and settles more than a few scores. His tone is anything but nostalgic.

Fox, now a resident of Amherst, was a paid employee of Salt City from 1978 to 1981. His memoir, parts of which have been circulating online for many years, focuses on those pivotal years. It was when the company launched its most successful and representative production, Andrew Lloyd Webber’s Jesus Christ Superstar, and company music director Pat Lotito premiered Yes!, the first of her memorable original shows.

The book could not be called a history in any sense because the author is careless with names and unreliable on dates, appearing never to have researched anything beyond his memory or informants’ shaky recollections. Most of the greater part of the Salt City story, such as huge hits like La Cage aux Folles or Me and My Girl, or artistic triumphs like Bill Molesky’s Sly Fox, came later and are never mentioned.

The book, which lacks a table of contents or an index, begins with the narrative technique of Citizen Kane, by introducing a character and then relating events from his or her perspective. Among the most important of these is lightboard operator Robert (“Studly”) Studdiford, who is portrayed favorably and to whom the book is dedicated. In such passages everything is seen from the point of view of the lightboard, with rapt attention to technical terms like “ellipsoidals” and “fresnels.”

But we miss most human details. The company enjoyed a hit with the musical Fiorello but we never learn the name of the lead. Sometime in 1978 Salt City Center opened an all-black production of Edward Albee’s Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf?, a landmark if not an artistic success. We never learn the names of the director or any of the cast.

Most of the dozens of people associated with Salt City are similarly absent. The late Christine Lightcap is cited three times. Frank Fiumano, Bob Brown (a baritone described as an “operatic tenor”) and Robert “Tank” Steingraber are barely allowed walk-ons.

Instead, Fox lavishes most attention on staff members, like black-clad ticket-taker Ruth Cope, and two forgotten players, Bill Brown and Cindy Volzing. Brown, the original Judas in Jesus Christ Superstar, was a volatile and explosive persona offstage, and later asserted the African portion of his heritage by changing his name to Mundaka Lee. Volzing sang the role of Mary Magdalene twice, but we closely follow her auditions for other roles, often finding herself in the chorus. Fox suffers from a disconcerting penchant for commenting on the firmness of Volzing’s breasts. She committed suicide in 1986.

The dominant figure in Fox’s book is, of course, Joseph N. (“Joe”) Lotito, the company founder, although we rarely see him in close-up. Through the early pages of the book the author’s approach is to bury a three- or four-line assault of Lotito’s behavior and personality failings while talking about something unrelated, such as Ruth Cope’s Quaker values.

Fox sneers at Lotito’s working-class, North Side origins and his reliance on paisan pals, and what he feels are failures in taste, like serving cheapo Andre Champagne in plastic flutes. Counterproductive to what are clearly the author’s intentions, Lotito becomes more formidable, like the Giant in the Jack and the Beanstalk story.

Fox, in a gesture to be fair and balanced, allows Lotito a few good roles: Tevye from Fiddler on the Roof, Willy Loman from Death of a Salesman, and Sir Thomas More in A Man for All Seasons. Yet he has no comprehension of what a profound personal sacrifice the Lotitos made to keep the place running in the teeth of constant adversity.

Neither can Fox give Salt City any credit for being a first leg up for countless young people, many from disadvantaged homes. Leaving aside Salt City veteran and Tony winner Steve Kazee, five members of the original cast of the blockbuster Phantom of the Opera (1987) proudly cited Salt City in their credits. Fox never saw them.

The Syracuse New Times comes off rather well in Fox’s account. He accurately retells the story of when the paper’s then-reviewer, the acerbic and feared David Feldman, was denied complimentary admission. The paper bought tickets for him.

The Salt City Playhouse is available from Amazon.com.