During its 10-year history, the ArtRage gallery has seldom hosted sweeping group exhibits. Thus, its current show, Seen and Heard: Embracing Our Past, Empowering Our Future, is an outlier.

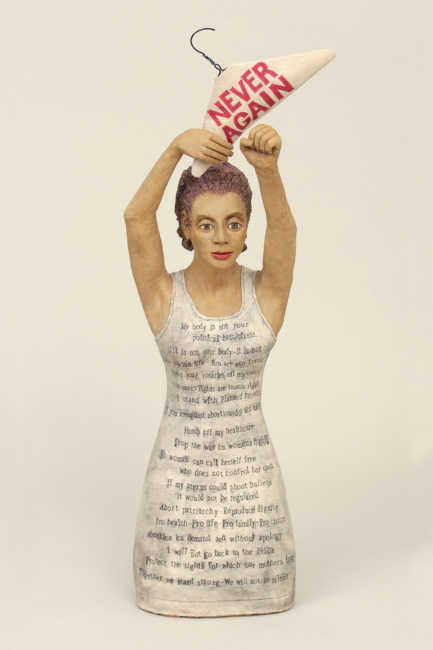

It has a roster of 17 women artists, displays multiple media, and encompasses themes ranging from life stages to reproductive rights, from killings of women by intimate partners to ways of communicating personal experiences. The exhibition both celebrates the gallery’s 10th anniversary and commemorates the 100th anniversary of New York state signing women’s suffrage into law.

There are works delving into topics that are all too familiar. In her ceramic piece, “Paper Trail Hate,” Mary Stanley combines bird-like creatures with representations of books such as Adolf Hitler’s Mein Kampf and Madison Grant’s The Passing of a Great Race, a 1916 text that served as a guide for the eugenics movement.

At the same time, there are references to publications such as The Universal Declaration of Human Rights, which first appeared in 1948. The work contrasts messages of hatred and tolerance and asks viewers to consider what’s going on in the world today.

Across the gallery, Joyce Day Homan’s “This Month” blends images of handguns and other weapons, women weeping, and text noting that each month roughly 46 women are murdered by current or former intimate partners. It’s a powerful work.

Seen and Heard presents a variety of other artworks, including Lisa Brasier’s images depicting two women in different stages of life. “Exit Stage Life” portrays a woman in her 20s attending a wedding reception, while “Beauty and the Lake” shows a silver-haired elder climbing up stairs after a swim in a lake.

Elsewhere, Gail Hoffman’s bronze sculpture again demonstrates her ability to communicate with miniature figures. In “We’re Still Here,” three girls look at a woman’s head positioned on a ladder that’s rising out of an abandoned building. The work is both concrete and out of time.

Mary Giehl’s “Adopt Me,” takes place on a shelf holding dolls without specific facial features. Just below them, children’s clothing hangs on hooks. Here Giehl is interpreting themes she’s incorporated into her art for more than 20 years: children’s vulnerability, their position in our society, the need to deal with abuse and neglect.

Several pieces utilize video. For example, Christine Chin’s “Hunter-Gatherer: Gather and Disperse Quilt” reflects on child rearing in contemporary urban society. She’s made a quilt split up by tiny video portals. There’s video footage of lactation, baby-wearing and other behaviors.

Lorena Molina created “Hit,” part of her Collective Trauma Series. It’s a gut-wrenching piece with video showing a woman being slapped again and again, and audio airing the repetitive sound of the slap’s smack.

Candace Rhea’s “Rilly and Her Doll” presents a young, brown-skinned girl holding a doll with blond hair and long legs. The piece looks at dolls from decades ago as cultural representations of an imagined, narrow ideal and questions stereotypes in general.

Such concerns aren’t merely anecdotal. Back in the 1940s, psychologists Kenneth Clark and Mamie Phipps Clark did research on the effects of stereotyped dolls on African-American children and later testified in a case ultimately merged into Brown v. Board of Education. It was heard by the U.S. Supreme Court and had a profound impact on education in the United States.

Emily Luther created two pieces, “Grief Receipt” and “Losing the Body.” The first work, a long series of intensely personal notes handwritten on paper, blends with the second, a video segment. They both discuss Luther’s own experiences and encourage dialogue on subjects such as childbirth, death, family and the female body.

The exhibition also includes Anne Cofer’s “Pillow,” with its subverting of floral patterns as an exemplar of domestic life; Cherie Spara’s self-portrait; and Vanessa Johnson’s newest work, “What We Carry-the 53%,” constructed from cotton fabric, nails, a mask, burnt log, cowrie shells and gris-gris bags filled with soil from Ghana and the United States. Ít’s part of a series calling for greater inclusion of women of color in the feminist movement.

These, and other artworks, help build a large exhibit with many connections: to the suffragettes, to the Seen and Heard exhibit on view at the Everson Museum of Art this summer, to current social movements.

In order to explore those links, ArtRage has scheduled a series of presentations: “Women Voted in New York Before Columbus,” a talk by Sally Roesch Wagner slated for Oct. 11 at 7 p.m.; a screening of Chisholm ’72: Unbought & Unbossed, a film about Shirley Chisholm’s groundbreaking 1972 presidential candidacy, on Oct. 15 at 7 p.m.; and an artists’ talk on Oct. 19 at 7 p.m.

Seen and Heard: Embracing Our Past, Empowering Our Future will be on display through Oct. 21 at ArtRage, 505 Hawley Ave. The gallery is open Wednesdays through Fridays, 2 to 7 p.m., and Saturdays, noon to 4 p.m. For more information, call (315) 218-5711.