If the late 1960s was the dawning of the age of Aquarius, a future where harmony, understanding, sympathy and trust would abound, an even more radical reality — electronic music — loomed on the horizon as well.

In fact, the eponymous theremin, the primitive tone generator that provided the creepy whine heard in many a science-fiction B-movie, had been on the market for some time, and the voltage-controlled analog synthesizer was under development by Robert Moog, a Ph.D. in electronic physics from Cornell University in Ithaca. Primitive as well by today’s standards, Moog’s transistorized synthesizer, a keyboard instrument, first met the public during a demonstration/concert at his Trumansburg facility on Aug. 28, 1965, a harbinger of future shock in the music business.

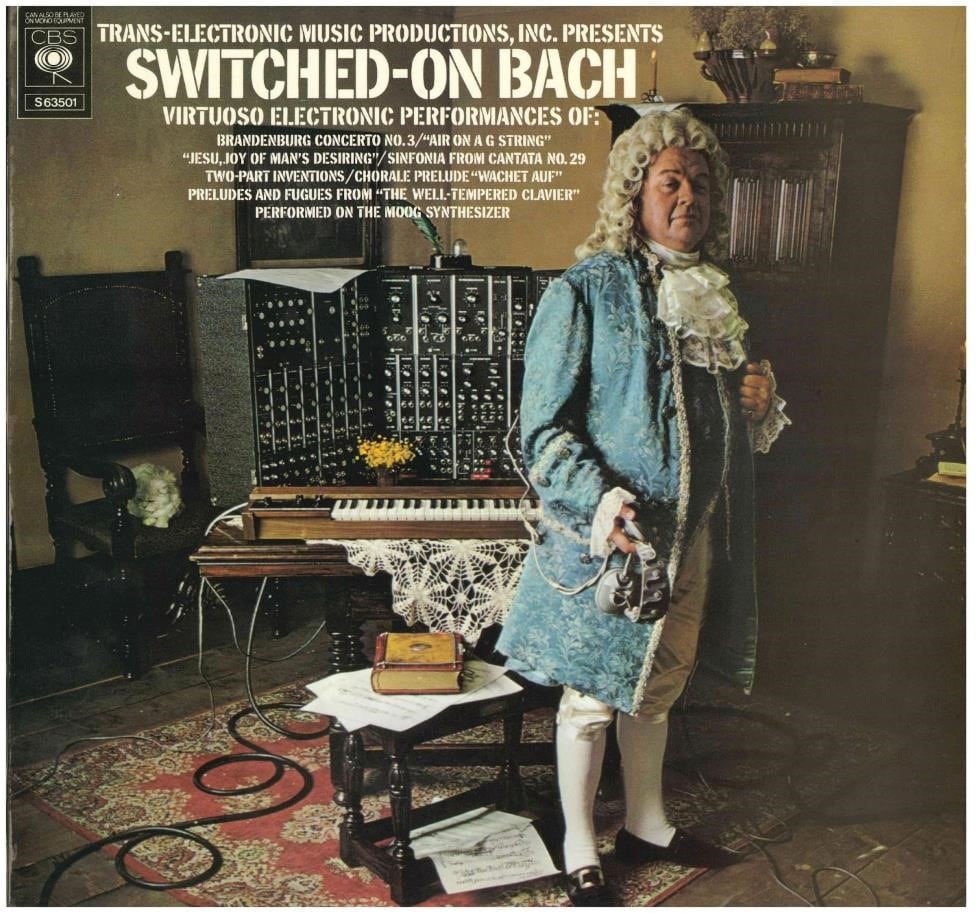

Two years later the Moog synthesizer was shown at the Monterey Pop Music Festival, an introduction that was destined to have long legs. More importantly, Moog met Walter Carlos, a recording engineer, composer and keyboardist, and producer Rachel Elkind that same year, generating a seminal collaboration that would lead to Switched-On Bach, the landmark LP that was unthinkable just a couple years earlier.

By 1967, Carlos — later to become Wendy Carlos — had already written and recorded several pieces for the synthesizer including the “Two-Part Invention in F Major” by Johann Sebastian Bach, the towering icon of the Baroque era. Expanding on that idea, Carlos and Moog envisioned a full-length LP of Bach’s music performed solely on Moog’s revolutionary instrument.

Referencing its electronic genesis, Switched-On Bach was released by Columbia Masterworks in 1968. Consisting of 10 selections, including the “Brandenburg Concerto No. 3,” the familiar “Jesu, Joy of Man’s Desiring,” “Air on a G String” and other inventions, preludes and fugues, Switched-On Bach dropped like a bunker buster on the world of classical music, fostering incredulity and pushback from classical music purists, who considered such treatment to be blasphemous. But those objections were quickly overwhelmed by the enthusiastic reaction of other listeners, including a young audience not otherwise considered to be interested in music written in the first half of the 18th century.

It had not been an easy project. Still in its infancy, the Moog synthesizer of 1968 was monophonic, capable of producing only one note at a time, requiring each voice — and there are many running concurrently in Baroque music — to be taped individually and layered together afterward.

To make matters even more labor-intensive, Moog’s nascent electronic wunderkind was colicky, frequently drifting off pitch and requiring constant readjustment. And then there was the challenge of choosing from the myriad of previously unheard of sonorities and effects The influential Switched-On Bach album celebrates its golden anniversary the machine was capable of generating and using them effectively. The whole project, end to end, took 1,000 hours of work over five months to produce barely 40 minutes of music.

In the end, it was all a smashing success. The public glommed onto the novel approach, a marriage of extremes, the improbable melding of ancient music and modern, experimental technology, vaulting Switched-On Bach quickly to the top of the classical charts where it remained for 49 weeks and as high as No. 10 on the Billboard 200.

In 1970 the daring LP was honored with three Grammy Awards: Classical Album of the Year, Best Classical Performance by an Instrumental Soloist and Best Engineered Classical Album. A rating of gold (500,000 albums sold) from the Recording Industry Association of America was not far behind, and in 1986 Switched-On Bach was certified platinum for selling 1 million copies, the first classical album to achieve that status.

A second collection of electronic Bach, The Well-Tempered Synthesizer, was released in 1969. And a 25th anniversary edition of Switched-On Bach was released on CD in 1992, followed by other reissues.

More significantly, Switched-On Bach immediately cast a long shadow, influencing a legion of composers and performers, especially in popular music, including Keith Emerson (Emerson, Lake and Palmer), Stevie Wonder, The Doors, The Beatles, the Beach Boys, The Who, Diana Ross, Rick Wakeman (Yes), adventurous jazz musicians Sun Ra (the Sun Ra Arkistra), John McLaughlin and Jan Hammer (the Mahavishnu Orchestra), pianist Bob James and many others. In 1971 Carlos went on to use the synthesizer on the soundtrack for director Stanley Kubrick’s quirky film A Clockwork Orange, performing original music and works by Beethoven and Rossini, further expanding the instrument’s footprint.

Fifty years after its release date, Switched-On Bach, an album that shared air space at its inception with Big Brother and the Holding Company’s (Janis Joplin) blues-rock staple Cheap Thrills, Jimi Hendrix’s psychedelic manifesto Electric LadyLand and The Beatles’ soundtrack for Magical Mystery Tour, presents itself as fresh and as innovative as ever.

The first cut, “Sinfonia to Cantata No. 29,” serves as a template for the album’s concept and character. Originally written for solo violin and later transcribed by Bach for a larger ensemble, this dynamic opening statement, especially at volume, is a giddy thrill ride replete with a wealth of alternate tonal colorations and the cavalier use of stereo imaging, where contrapuntal voices bounce playfully from channel to channel. All of this was unimaginable in the composer’s lifetime.

What would Bach have thought of the synthesizer? Would the grand master of the Baroque, the endlessly daring and improvisational innovator, have dismissed this instrument as irrelevant, an ephemeral trifle to be ignored? Or would he have embraced the protean keyboard as a potent, expressive option, and chosen to explore its possibilities and have his way with it? I think I know the answer.