Ginger Peterman learned a long time ago that a person must create her own opportunities in places that seem impossible to do so, especially if she is limited by society.

Peterman was 23 when she joined the military, and was almost immediately deployed to Iraq. She served as a truck driver from March 2007 to December 2009. During her time in Iraq, she was sexually assaulted and experienced sexual harassment on a regular basis.

“The military culture is one that is not necessarily friendly to women,” she said. “People treat you as if you’re just there to look pretty and have sex. And if you don’t want to, they will force you.”

According to Peterman, many military authorities downplay sexual harassment and assault, especially if the victim was able to get away.

“I didn’t really feel validated that I was experiencing military sexual trauma, and having PTSD (post-traumatic stress disorder) as a result of that experience,” Peterman said. “At first I thought nothing happened, I’m fine. I’m good. But it’s the same thing: You still suffer the same sort of consequences even if you got away.”

After serving in Iraq, Peterman says she felt like a completely different person. “I didn’t want attention from guys anymore because of all the harassment and sexual advances I had gotten in the military,” she said.

It also affected her ability to trust others. Although Peterman received support from family, friends and colleagues, she said she still felt very isolated, and saw everything around her in a different light.

“It’s kinda like that movie Monsters Inc. Don’t you think it would be better if we gathered laughs instead of screams? Instead, we’re in a world that gets its energy from terror, from people screaming,” Peterman said.

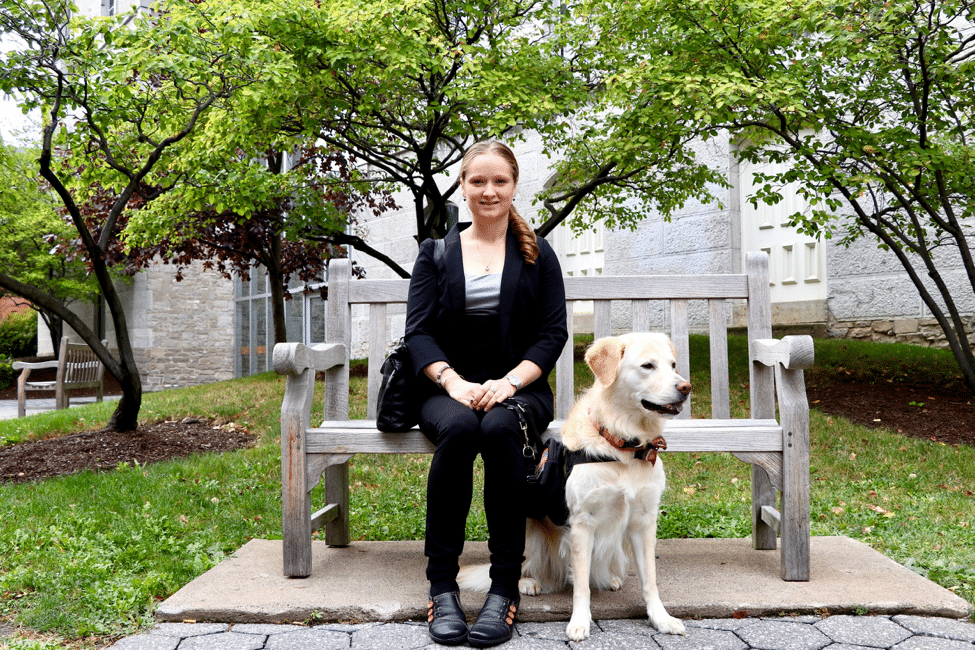

Now 33, Peterman is a Ph.D student at the School of Information Studies at Syracuse University, where she is studying biomedical engineering. She hopes to create a device for veterans with PTSD, and has already received $3,000 in seed funding to start up a prosthetics company.

Peterman also has a 7-year-old son, Charlie. Although it has been hard for her to connect with him at times, she hopes to show him what she has learned from her experiences.

“I try to explain to him how things are socially constructed. Things were built before I was born, and those things are still standing,” she said. “They can change, but it takes time, it takes disaster, it takes strength and resilience, it takes people who care.”

Through the device she is currently developing, Peterman hopes she can help other veterans who have PTSD. “The whole thing with post-traumatic growth is being able to take your weaknesses and experiences of oppression, and create an opportunity out of that. Not just for yourself, but also to carve a path for others to follow, to lead by example, to show others you can take your struggles and weaknesses, and create purpose to make a better society.”

“I will always place the mission first. I will never accept defeat. I will never quit.”

— An excerpt from “Red White and Blue, and Orange” that Ginger Peterman wrote for the Institute for Veterans and Military Families at Syracuse University. Read the full piece at bit.ly/2hH0Wc4.

Deanna Parker

When Deanna Parker graduated from college with a bachelor’s degree, her future felt uncertain.

Parker is now the program manager at the Institute for Veterans and Military Families at Syracuse University (IVMF), where she leads the Entrepreneurship Bootcamp for Veterans with Disabilities (EBV) and Veteran Women Igniting the Spirit of Entrepreneurship (V-WISE) programs.

After teaching for two years, Parker decided she wanted to join the military. Her brother had joined the Marine Corps just a year before that, and Parker was intrigued. She wanted to be in the action, not behind a desk.

She contacted officer recruiters in the Marines but got no response. Desperate, she approached the officer who had recruited her brother and was able to apply.

Parker was the only woman in a class of 46 people. When her batch was about to graduate, she learned that she was going to be held back for a week because the authorities did not want to put a female through by herself.

“When I heard that was happening, I went to anybody that I could talk to, and I said, ‘If you want me to sign something, I’m not going to sit here and wait for a week,’” Parker said.

She was being held back due to safety concerns, but she ended up graduating with the rest of the batch. But her fight was just beginning.

All of her peers were sent to their prospective units, but Parker was placed in the company office. At the time, she didn’t know why and wondered whether it was because she was a woman.

At the office, Parker completed paperwork and worked as the commander’s driver. Although she learned a lot, helped many people, and picked up skills that she would use later in her career, she was not happy. “I was very frustrated, but I kept on going and did my thing,” she said.

Her situation worsened when she discovered there were some people working in the office who were only there because they had done something wrong, such as driving under the influence. Parker later published a paper titled “Office Hours,” which detailed the implications of trust-ing people with a history of offences with important information in company offices. Her paper was published by the Marine Corps.

Shortly afterward, Parker was offered a job at a legal office, after which she was sent to a deployable unit with 40 males and no other women.

According to Parker, being the only woman was both good and bad. “I didn’t have anyone I could really connect with, but I also didn’t have to deal with any drama,” she said. “If I could do it over again, I’d probably do it the same way.”

However, Parker said there were times when she struggled to find people with whom she could share her experiences and feelings. When asked what she would tell herself if she could go back in time, she said she would tell herself to seek out healthy friendships.

“I would go back and pull other young female Marines alongside me, whether it be for friendship or mentorship.”

Christine Tarnowski

Christine Tarnowski has always wanted to be part of something bigger than herself. This could have been the reason why the current senior director of operations at the Institute for Veterans and Military Families at Syracuse University found herself walking into an Army recruiter’s station in 1987.

After enlisting, Tarnowski moved up the ranks, from working in a warehouse to holding a top position in the Army.

Tarnowski has been married, divorced, pregnant and remarried, and has worked throughout most of her life, primarily because as a woman, she felt she had to prove herself in a field that hasn’t traditionally been accommodating of women.

Because of her busy work life, her children weren’t able to participate in a lot of activities growing up, especially because Tarnowski was a single parent for a while. However, Tarnowski also said there are more support systems for veterans with families, like day care centers for children, help from friends and family, and an overall sense of community.

However, there were times of struggle, and one event catalyzed Tarnowski’s decision to leave the military and move on to the next thing, ultimately bringing her to Syracuse. Tarnowski’s commander purposely took her off a deployment list without consulting her, because he felt it was more important for her to stay at home and take care of her children.

“It was very thoughtful of him, but without a deployment, I wouldn’t be able to get promoted,” Tarnowski said. “It was probably the right decision for my family in that point of time, and I don’t regret leaving, but had I been a man, I don’t think the same outcome would have transpired.”

However, Tarnowski said her experiences in the military have greatly affected her view of life. “I would not trade it for the world because it is very rewarding. You completely understand what the level of commitment means and how different that can be from civilian life. It makes you appreciate the smaller things in life.”

She also advised aspiring and current young women in the Army to be conscious and careful. “Be cognizant that your actions have a direct reflection not only on yourself, but on others.”