Natisha Foster was waiting for the bus home on Saturday, Aug. 30, when a commotion on South Salina Street caught her attention. She turned and saw a crowd of about 50 people following a pickup truck, carrying banners and signs, chanting as they marched in the middle of the road behind a police escort.

The marchers had come from the Southwest Community Center and were headed to Clinton Square, calling out in solemn cadence for an end to violence in the streets.

“What do we want?”

“To stop the violence.”

“When do we want it?”

“Now.”

Michael Davis Photo | Syracuse New Times

Foster, an unemployed nurse and mother of three, erupted into cheers. She clapped and shouted until tears filled her eyes. She lives on Ballard Avenue, near the course of the march that the peace advocates had just taken.

“I’m raising my own son,” says Foster. “He’s 10 years old, and I’m so afraid. I won’t let the streets get to him. Too many of our black men are killing one another. I can’t imagine the sorrow and the pain – I don’t want to see another mother go through that.”

One of the marchers in procession that Foster witnessed was Helen Hudson, a councilor-at-large long known as the leader of Mothers Against Gun Violence.

Michael Davis Photo | Syracuse New Times

“I’ve seen three generations of our young people lost on the street,” Hudson told the marchers when they arrived at the fountains at Clinton Square for a rally to conclude the march. “That’s well over 400 people. If you don’t believe me, go up to Oakwood (Cemetery).”

Hudson says she has been to at least 30 such marches and vigils, but this one was different: It is the first one organized by the younger generation.

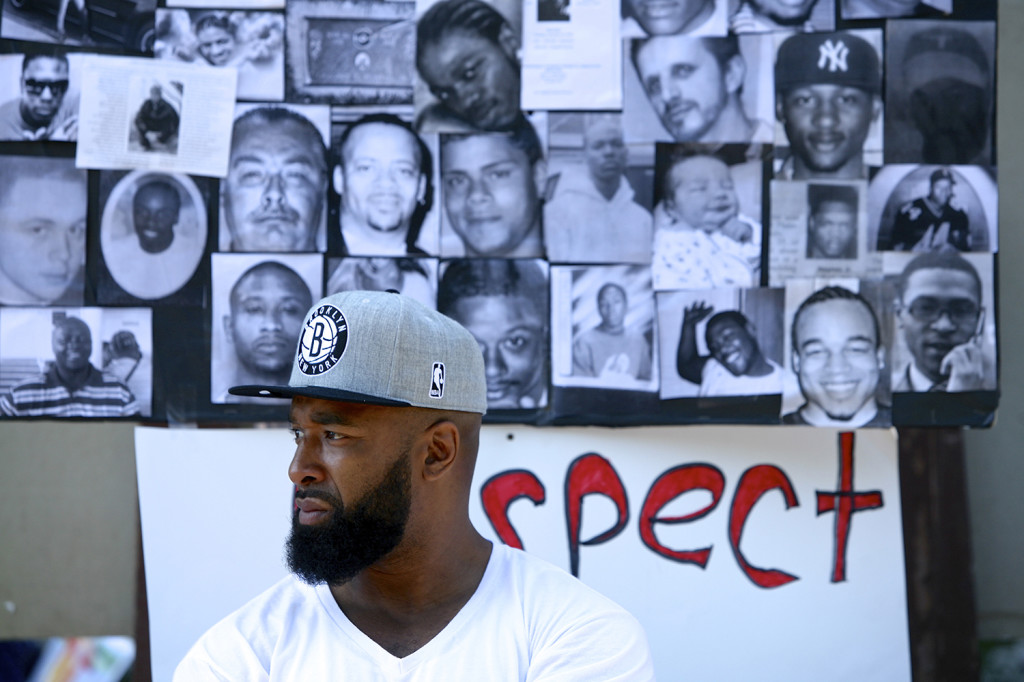

Ed Mitchell is one of the young leaders who organized the march. Mitchell, 27, a Corcoran High School graduate, said he has seen enough. He’s grown tired of watching young people in his neighborhood wasting their lives, or worse, getting killed. He was talking to his friend, Charles-Anthony Rice, about the killing of Michael Brown in Ferguson, Mo., when the idea emerged for a march in Syracuse.

Michael Davis Photo | Syracuse New Times

“There’s a lot of uproar about the Michael Brown shooting,” says Rice, “but nobody marching for the young people we lose every weekend, people that we lost to each other. A lot of our young people are crying out and no one is listening.”

One of the people listening to Rice and Mitchell converse a few weeks back was Lawrence Williams, a former city school teacher, probation officer and director of the city’s effort to reduce gun- and gang-related violence. His effort was recently renamed SOY (Save Our Youth). Williams saw it as his role to teach the younger men how to organize a march.

“They felt that the Michael Browns in our own community are losing their lives at the hand of other Michael Browns,” Williams says.

Having survived childhood in a violent neighborhood, Mitchell feels a duty to do something to help today’s youth.

“I grew up around a lot of people who went to jail, people who died in front of me, died around me. You want to do something different. I talk to a friend one night, next day she’s gone to jail. I am blessed, I’ve got opportunity. I made it out, many didn’t.”

Michael Davis Photo | Syracuse New Times

He tells a story of a party six years ago. He was a chaperone. Shots rang out. Mitchell went down, a bullet in his leg. It doesn’t keep him off the basketball court, but all these years later, he can still feel the pain at times.

“Anybody can be a victim,” he says. “You can be doing nothing. Anything can happen. Kids just shoot because they’re bored. We don’t want to lose any more children to violence, black-on-black violence. We want to get some awareness that we are losing kids day to day.”

“We want (the young people) to know that there are avenues they can take. Those avenues include a handful of programs, including Team Angel, Journey2Manhood, SNUG and others,” he says. “We want to inform parents that it does start at home. We lose young people due to stupidity. We can’t march for Mike Brown until we start here.”

Police Chief Frank Fowler marched along the whole parade route, and said that he sees hope in the cooperation his department has been getting from the community.

“Overall, this has been one of the better summers,” says Fowler. “The numbers tell the tale. We have had certain spurts of violence, but the level of cooperation that we’re getting from our city is great.”

For example, notes Fowler, last week the police department arrested a man accused of two shootings on Kellogg Street earlier in the summer.

“On Thursday, we sent out a press release about three dangerous criminals. Next day, we got a very good tip about a murderer, and he was apprehended.”

Asked about the numbers of murders this summer, Fowler echoes the statement made by many at the rally: One death on the streets is one too many.

Keeping the streets safe, says the chief, comes from “working together every day at a time when the tears are not flowing, the bullets not flying. It comes from building relationships.”

Michael Davis Photo | Syracuse New Times

While much of the focus of the rally was on young men, the loudest voices were a group of young women, including Ryneshia Robinson, a 2009 Corcoran graduate who will soon be joining the U.S. Navy. Robinson shows the poise she acquired as a Corcoran cheerleader. Now she and her friends gave up a sunny afternoon on one of the last days of summer to cheer for a different reason: her 4-year-old son.

“When I had my son, everything changed for me. There used to be a lot of support in our community, but we’ve lost that. But we can get it back.”

Ed Griffin-Nolan is a journalist who believes we have to ask the hard questions no matter whose interests are at stake.