I was driving last summer with a friend on Syracuse’s Southwest side when I observed the abandoned structure at 411 Seymour St. When we exited the vehicle to take a closer look, several curious neighbors stopped to talk about the community. I briefly noted the mention of a large funeral taking place at the address years ago, but my attention quickly shifted elsewhere.

I recently returned to take another look at the Seymour Street home, and realized that I had been doing what historian Richard Dean says has been happening for decades: “Everyone is forgetting about the Battle of Columbus.”

The year was 1916. Private Thomas F. Butler, a Syracuse resident, had entered the military and was stationed at what is now known as Camp Furlong in Columbus, N.M., where he served as a member of the 13th Cavalry Regiment. According to Dean, the regiment acted as a border patrol unit. Butler spent his days on horseback riding east to west, west to east, along the U.S.-Mexico border, ensuring that anyone crossing into the country stopped at a customs house and paid any necessary taxes.

Just south of Butler’s post, a bloody civil war was raging in Mexico, as several regimes were fighting for power. One of those rebellion leaders was Francisco “Pancho” Villa.

While battling for control in Mexico, it’s believed, but still debated, that Villa became upset that the American government seemed to have shifted its support from him to an adversary, provoking him to respond with force.

Before dawn on March 9, Pancho and his men, known as Villistas, moved north and attacked the people of Columbus, burning their settlement and looting their homes. Surprised but prepared, the soldiers and residents acted quickly, engaging in battle until the Villistas retreated in less than two hours.

In the end, 18 Americans perished at the hands of the Villistas: 10 civilians and eight soldiers. This is the last time the United States was attacked by a foreign power with boots on the ground.

One of those killed was Pvt. Butler. Col. Slocum, commander of the 13th Cavalry, listed Butler’s injuries on the casualty report as two bullet wounds to his arm, and another to his chest. He was 27.

The house on Seymour Street was Butler’s family home.

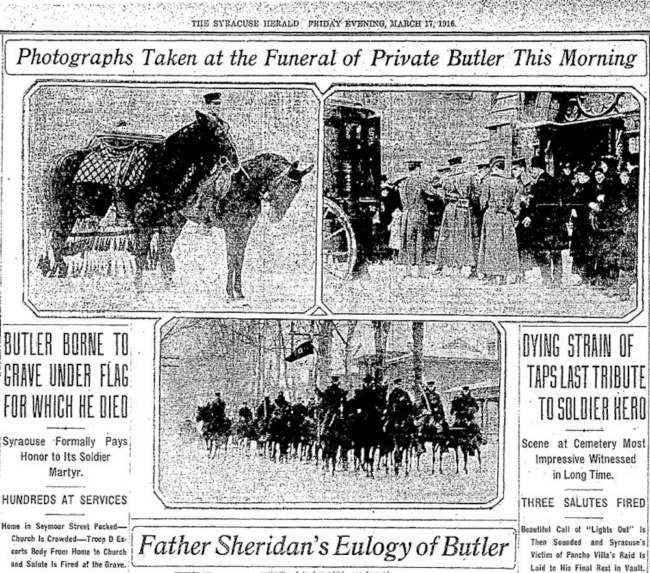

Upon his death, Butler’s body was returned to Syracuse by train on March 16 and a service was held the next day. The Syracuse Herald described the service by stating, “Seldom has there been a funeral service in Syracuse as impressive as that of Private Butler.”

Beginning on Seymour Street, Butler’s body was displayed within the home as hundreds gathered inside. Outside, hundreds more filled the street to honor the fallen soldier.

Following a prayer service, Butler’s body was transported by horse carriage to St. Lucy’s Church in a procession that included family, friends, veterans and public officials. Father Sheridan gave the eulogy and spoke of Butler’s dedication to our country: “Greater love hath no man that this, that he lay down his life for his friend.”

The ceremony ended with a second procession to a snow-covered cemetery at St. Agnes, where salutes were fired as Butler’s body was placed in a vault until a spring burial at St. Mary’s Cemetery.

Following the battle, President Woodrow Wilson ordered the U.S. Army into Mexico to capture Pancho Villa, an order never fulfilled. Villa retired from the battlefield in 1920 under an agreement with the president of Mexico, but was assassinated three years later as he attempted to regain political power.

Today there is no marker, no honor and no celebration for Private Thomas F. Butler in Syracuse, but that is not the case in Columbus.

The town commemorates the attack with an annual day known as “Fiesta de Amistad” — a celebration of friendship. The event is highlighted by a journey on horseback where Mexicans and Americans meet at the border and ride together the three miles to Columbus, holding both American and Mexican flags in a sign of peace and goodwill.

John Read, park manager for the Pancho Villa State Park, states that Butler’s name is read annually at the ceremony. He recognized it immediately when I called to inquire about the park, adding that there is a plaque that bears his name on the grounds.

The park, named after Pancho Villa, opened in 1961 and sits directly across the street from where the majority of the battle took place. Before I could question why the park was named for the man who directed an attack against the United States, Read acknowledges the name has been the subject of many discussions, but he supports it. “The name has created an important bond with the Mexican community,” he said, “one that I don’t want to break.”

Read also accepts the opinion of his friend and mentor Richard Dean, the Columbus historian who has spearheaded efforts to change the name. Dean, whose great-grandfather, James T. Dean, died alongside Butler in the Battle of Columbus, stated, “It’s like New York City naming a park after Osama Bin Laden. We shouldn’t honor a terrorist.”

Nonetheless, both men agree upon the importance of the event, which also includes lectures, dances, vendors and even a look-alike contest.

So as long as the park exists, John Read, Richard Dean and the rest of Columbus, N.M., won’t forget about the Battle of Columbus, and in doing so they’ll continue to remember our beloved Syracuse son, Private Thomas F. Butler.

It’s time we find a way to remember him, too.

David Haas writes about Central New York’s historical legacies for his website storycuse.com.