It’s 17 feet wide, and a precise 100 feet from the front door to the back wall. That makes for 1,700 square feet, about the capacity of a suburban tract house. Into that space the management of the Manlius Art Cinema has squeezed a ticket booth, a concession stand, two toilets and 200 seats, usually eight per row, two on the left side of the aisle, five or six to the right.

This unlikely parcel has survived a century, defying changes in technology, economics and public taste to become the oldest continuing movie house in the area. And not just still here but thriving, thanks to unexpected successes like the documentary RBG on Supreme Court Justice Ruth Bader Ginsberg, which flooded the coffers. To celebrate the theater’s birthday, the Greater Manlius Chamber of Commerce will host a ribbon-cutting ceremony at the cinema on Friday, Dec. 7, 6:30 pm.

The configuration may have stayed roughly the same, but the building has gone through a series of managements, name changes and missions. A fire gutted the place in the 1940s, while the long run of the South African comedy The Gods Must Be Crazy in 1985 prompted a major remodeling. It was first a neighborhood bijou, later a rerun house, and not an art house venue until more than 50 years after the initial launch.

Arthur and Arvilla Eastwood opened the Strand Theater at 135 E. Seneca St. in Manlius on Dec. 6, 1918, less than a month after the Armistice. It was not the first movie house in the village, as two rivals, the Star (1913) and the Marion (1914), had opened previously and ran in competition for a while. The first Strand feature was the 60-minute silent Sunset Trail with Vivian Martin. Admission was eight cents, or three people for a quarter with a penny change. The Eastwoods were not seeking an elite demographic.

The village of Manlius, founded in 1813, older than Syracuse, was a satellite town then and would not become an affluent bedroom community for another 30 years. Rumor once had it that the Manlius was the oldest cinema in the country, but that’s a mare’s nest of a debate no one wants to enter.

Movie houses, where audiences sat down, as opposed to the earlier nickelodeons, are usually dated from the introduction of feature-length films in 1912. The advent of ambitious directors like D.W. Griffith increased the length and quality of the product, but business did not get big until 1920. The modest opening of the Strand in Manlius anticipated by two years the coming of the great movie palaces of the 1920s, of which the aptly named Palace (1924) and the Landmark (1928), formerly Loew’s State, are our most prominent survivors.

Most old cinemas, of course, do not survive. As the late Norman Keim points out in Our Movie Houses (Syracuse University Press, 2008), when the buildings were not sufficiently profitable, there was little else to do with them. It was not until the rising cultural prestige of the movies in the 1970s that the palaces were preserved, but 135 East Seneca could never rely on its good looks alone. Keim also reminds us that there were once about a dozen Manlius-sized houses in Syracuse neighborhoods that are all gone, even the street addresses. Easier profits can be turned on choice property that’s inactive much of the day.

Current owner Nat Tobin remarks that investors have sought to buy him out and tear down his entire block. He is not selling. Another says, “When you want to retire, let me know.”

Although Tobin switched to digital projection at the Manlius in 2012, to cope with the disappearance of actual film, previous owners were not always at the cutting edge. A year after Arvilla Eastwood sold 135 East Seneca to F. Denison Richburg and W. Howard Judge, they added sound in 1931, four years after Warner Brothers released the talkie The Jazz Singer. They renamed the place the Seville.

Sources disagree about the duration of different names, but it was called the Lincoln, Seville and Strand at different times. When sold for $20,000 on Sept. 10, 1948, it reopened as the Colonial.

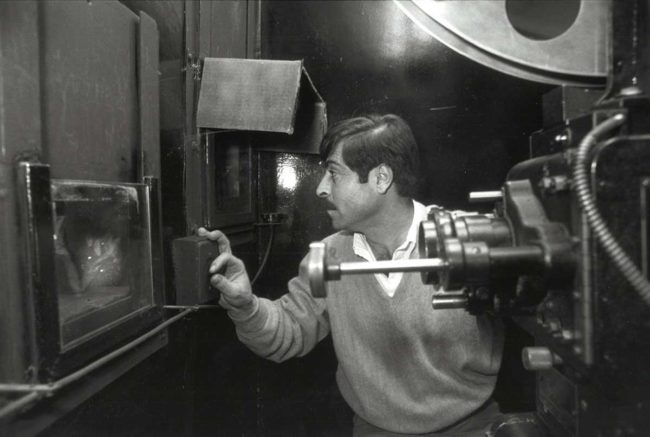

Longtime area projectionist Jack Dumas recalled working inside the cramped booth in the early 1960s, back when it was known as the Billings. It was called the F-M Theater in 1970 when a newspaper ad announced that there would be a matinee for the James Bond thriller On Her Majesty’s Secret Service (with George Lazenby), “only if it rains.”

The owners who changed directions for the Manlius were Sol Sorkin (no relation to playwright Aaron Sorkin) and his son Robert, who took over in the early 1970s. They sensed that the theater could flourish with the niche market for foreign and independent films. The emergence of the “art” or “select” house came with the influx of foreign films after World War II, like Vittorio De Sica’s The Bicycle Thief and Jean Cocteau’s Beauty and the Beast that many theater chains refused to show but that a determined audience clamored to see.

For three decades Syracuse’s prime art house was the palace-like Riviera Cinema, 3120 S. Salina St. Despite a roof collapse in 1968, it lingered into the early 1970s with different offerings, reruns and occasional soft-core fare, as audiences, rightly or wrongly, became reluctant to visit the neighborhood.

Simultaneously, the market for art films expanded and could draw audiences to three enterprises. The 746-seat Westcott, built in 1926, and remodeled and renamed the Studio from 1968 to 1975, could be a successful art house — if only audiences could find parking. It would be linked to the Manlius eventually before being converted to a live music venue in 2007. And the Mini-One sprouted up next to the Cinema East on Erie Boulevard East, 1966 to 1991, and often showed indie and foreign product, depending how the box-office wind was blowing.

An interloper competing with these theaters was Protestant Chaplain Norman O. Keim at Syracuse University, later to write Our Movie Houses. He was running first-run foreign features with 35mm projection under his Film Forum banner on campus during the academic calendar. In the summer months he could fill the then-shabby Regent (built 1914), later remodeled to become the home of Syracuse Stage. In 1968 Philippe De Broca’s King of Hearts did sellout business after having been a bust elsewhere. This prompted Keim to gain national attention and to host academic-looking retrospectives, then a novelty, with luminaries like Henry Fonda, Claire Bloom and Rod Steiger.

The Sorkins’ task was to lure the Film Forum and Westcott audiences to drive a half-hour to the east, with the promise of more parking. Father Sol complained to distributors that Keim’s Film Forum was unfair competition as a nonprofit. His Manlius did succeed in getting fresher releases, but Film Forum lingered on, diminished, until the early 1980s. The most talked-about feature from the Sorkin era was the lubricious X-rated Caligula (1979), produced by Penthouse publisher Bob Guccione. Young Robert Sorkin, a personable film buff, often ran the day-to-day business at the theater. His sudden and unexpected death in the early 1980s led to the sale of the house to Sam Mitchell.

An experienced hand in the movie business, Mitchell owned a string of movie houses in different upstate towns. He lived nearby and expressed a fondness for the Manlius, even though he pretended no special expertise in art films. He did feel, however, the Manlius would do best sticking with that market niche. He also followed the offerings of the Central Square Cinema in Cambridge, Massachusetts, which served both a university and a general audience.

That strategy paid one huge benefit with the slapstick comedy The Gods Must Be Crazy, possibly the biggest hit in the venue’s 100 years. Made four years earlier and not released until late 1984, Gods looks clumsy under today’s scrutiny and does not hold up well. Yet after its 1984 opening, it played to turn-away crowds through winter and spring 1985. The Manlius was not alone as Gods, although forgotten today, was also a nationwide sensation.

With the largesse from Gods, Mitchell completely remodeled the house, installing the current seats, moving the aisle from the center to the right. He also extended the auditorium by about a third but left the banking uneven. This plus an archaic draining system led to water problems for current manager Tobin about 15 years ago, now solved but unfortunately remembered.

Within the next year, however, Mitchell would turn over management of the Manlius to Ghaleb al Nwairan, a recent immigrant who spoke English as a second language. Al Nwairan claimed no great knowledge of the movie business and even less of art films, but he forged ahead. He experienced the greatest controversy in the cinema’s history with Martin Scorsese’s Last Temptation of Christ in 1988, attracting righteous protesters. In a press interview, al Nwairan said that he welcomed the protests and that the box office declined when they withdrew. Unable to complete a purchase of the Manlius, al Nwairan departed, and the management came into the hands of Nat Tobin in 1992, ushering in the most stable 26 years of the house’s history.

A native of Fresh Meadows, Queens, Tobin entered the movie business with the fabled United Artists company. After the catastrophe of Michael Cimino’s Heaven’s Gate (1980), a United Artists release, purchaser MGM sought to close the New York City office. Tobin connected with Crescent Advertising in Syracuse, which represented the then-dominant local chain CinemaNational, which through various purchases became USA Cinemas, Loew’s, Sony, Hoyts, and now Regal.

In those 12 years Tobin had come to know Sam Mitchell well and was happy to start running the Manlius. For more than a decade Tobin also ran the Westcott, which Mitchell also owned. That meant the two art houses were complements rather than rivals.

Tobin’s first feature when taking over the Manlius was the Italian war comedy Mediterraneo, which ran eight weeks and won a surprise Oscar for Best Foreign Film. Tobin asserts that it is still one of his favorites. It lacked big names but Manlius audiences have usually read nationally published reviews before films arrive in town.

Many of the Manlius’ successes have turned on the major chains’ myopia. Neil Jordan’s The Crying Game (1993) ran for 10 weeks, and Nia Vardalos’ My Big Fat Greek Wedding (2002) for 22 weeks. But Tobin will also opt for commercial releases he thinks his audience might embrace, like septuagenarian Sally Field’s recent comedy Hello, My Name is Alice.

From first video stores and later Netflix, Tobin has warded off threats not imagined by owners in the first 50 years. Among the worst is the decline of the single-screen house as a business model. His response has been “the talk,” an approach he learned from a single-screen movie house owner in Paris, up against big-time competition. Neither a pep talk nor an in-person commercial, Tobin’s pre-show chat plays up some hidden aspect of the film or a connection to another film the audience might remember. He feels that it enhances the social interaction of the audience, and reminds people that the Manlius Art Cinema is their own.

Tobin and wife Eileen Lowell bought the Manlius from Sam Mitchell in 2007, meaning that all decisions are their own. One move that has strengthened the house is the addition of alternative content, such as productions from London’s National Theatre Live and the Royal Shakespeare Company.

The admission cost has gone up since 1918, but is still only $10 for adults and $9 for seniors, students, children and military members as well as for matinees.

On Saturday, Dec. 8, however, the theater reverts to its World War I-era price (10 cents!) as it screens a quintet of special features. Steven Spielberg’s 1982 science-fiction treat ET: The Extraterrestrial starts the day at 12:30 p.m., followed by Moonrise Kingdom (2012) at 3 p.m., In Bruges (2008) at 5 p.m., Loving Vincent (2017) at 7:30 p.m. and the Coen Brothers’ 1999 cult comedy The Big Lebowski at 9:30 p.m. The management requests that exact change would be helpful for admission.