AHOY Comics is what happens when two former Post-Standard colleagues, writer Hart Seely and artist Frank Cammuso, start brainstorming.

“Well, me and Frank were sitting around one day,” Seely recalls, “and we were trying to figure out what the hell we were gonna do, and we just kinda said, ‘Why don’t we start a comic book company? Why don’t we have a small boutique line of comics and do what we wanna do?’ And (comics veteran writer) Tom Peyer was perfect for it. And that was that.”

Seely, Cammuso and Peyer started to plan AHOY Comics in January 2017. They spent that year learning the nuts and bolts of publishing and contracts, assembling expert help, lining up the company’s first projects and hiring creators. Seely took on the publisher’s reins, with Peyer as editor-in-chief and Cammuso as chief creative officer.

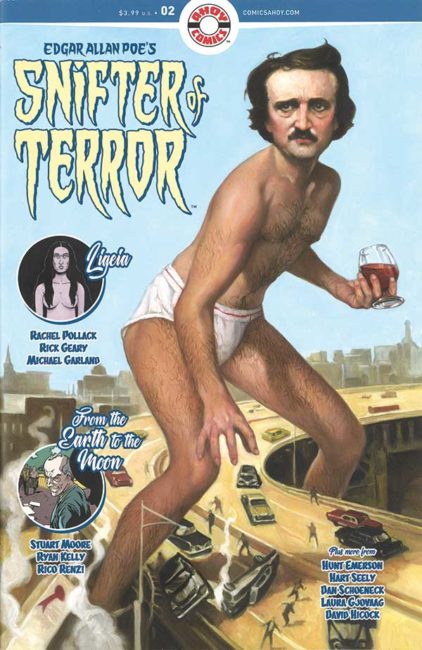

After a long gestation period, AHOY published its first comic, The Wrong Earth, in September 2018. It was quickly followed by three other monthly titles: the religious satire High Heaven, the bizarre anthology Edgar Allan Poe’s Snifter of Terror and the outer-space antics of Captain Ginger.

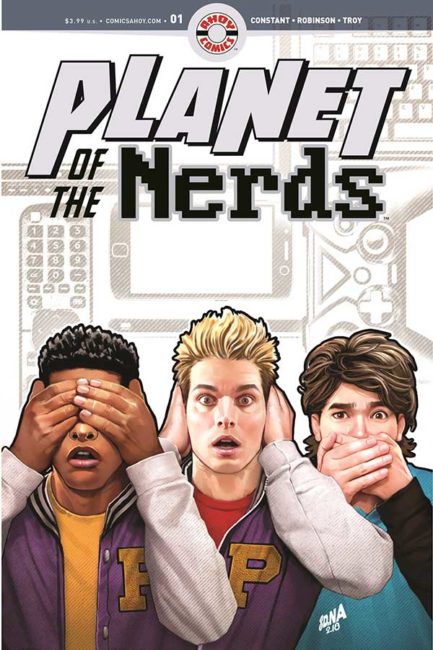

The company has announced a second wave of new titles: Bronze Age Boogie and Planet of the Nerds in April, Hashtag: Danger in May and the one-shot pilot showcase Steel Cage in June. AHOY will also have the superhero issue Dragonfly and Dragonflyman available during the annual Free Comic Book Day, which takes place May 4 at area comic shops.

The price for each 40-page AHOY issue line will be $3.99. Peyer notes that he took a cue from the old Gold Key Comics line of the early 1960s, with a reprint of the front cover on the back, sans logos and subheads. The stories even have page numbers, another old-school touch.

AHOY is an acronym standing for Abundance, Humor, Originality and Yes!, although longtime local fans of the former AHOY award bestowed each year by Peyer and Seely on an undeserving national figure will know another phrase for the acronym.

Yet the AHOY honchos figure the time is ripe for a start-up comics company that offers unique storytelling, quality printing and unorthodox humor. “As editor-in-chief, it’s my job to make sure the comics are good in a way that I want comics to be good, and to make sure they come out on time,” Peyer notes. “I always say, ‘My job is if anyone tries to kill the comic book, it’s up to me to kill them.”

One of your heroes, Marvel Comics icon Stan Lee, said that when he started out people would ask him what he did, to which he responded with “I’m a writer.” And when they asked “What do you write for” and he told them, they’d walk away. Are people still walking away?

Tom Peyer: No, they’re not. I am really full of admiration for people who worked for comics in the 1950s. They were maligned, they were badly paid, they didn’t own any of their work, and yet they still did amazing work and pushed the medium forward. To me, they’re martyrs. And Stan Lee is one of the reasons we don’t have to be martyrs anymore, because he started writer comics that older people could enjoy. And he was such as great pitchman with this amazing reputation as an important media figure, and that helped everybody.

Frank Cammuso: No, when people ask me what I do and they find out I’m a cartoonist, they actually get excited. I think they find it very interesting; they ask where I draw comics for, or where they can find them. Comics aren’t the dirty little secret they used to be.

Hart Seely: No, not at all. In fact, comic books have achieved an amazing prominence in American culture these days. The simple fact that there are comic book conventions all across the country is an amazing evolution. And the subculture of comic books is incredible,

In the 1950s and 1960s when all of this was building, comic books did have a reputation for being simplistic and such. Nowadays they are the cutting edge of movies with the CGI (special effects) that is in every movie about a comic book hero. If they put out a superhero movie these days, it’s a $100 million breakout blockbuster. Nobody does a comic book movie on the cheap anymore. Comic books are huge.

Stan Lee pointed to energy as being a major factor in the change.

Tom: I don’t know if he was referring to energy from the audience, but that is a great thing from the readership, and again, he really helped that whole situation. I was a kid when Stan’s comics were coming out. We were all on a first-name basis: He was Stan and he had this wonderful disc jockey patter in the letters pages and in the text pages he wrote. He made it feel like he was our pal. So there’s a great back and forth with the readership, and he’s one of the reasons why.

You have made the point that you don’t worry about the kids, you worry about the parents. Should there be limits on access to comics based on age? And what would you call it: an adult comic book? What do you call it?

Tom: Well, families differ from each other. Some families are open to a wider range of materials than others that they would approve of letting their kids see. What we, and most comic companies do now, is if something is really intended for adults, we label it “Mature.” Generally, most comics break down into all-age books, teen books and mature books, so there is a rating system in place, and we follow that format.

Frank: I think there are limits, but since comics are visual you can really tell. A certain art style, more cartoon-esque, will appeal to younger kids, whereas older kids will probably go for a more realistic art style, and that’s really how a lot of visual literature is disseminated. If you have a certain look to your work, you’ll be in a certain age group.

My work skews what you call “Early Grade” and “Early Reader” and that really is a good way to tell. For example; young kids love Mickey Mouse, whereas an older kid would be more drawn to Batman. And that’s as much as I’d differentiate an adult comic from a kid’s comic.

Hart: We have had different targets for each of our books. The Wrong Earth is a send-up of comics, and Edgar Allan Poe’s Snifter of Terror is a send-up on a great American writer. They definitely go for the adult audience. High Heaven goes after the Catholic church and it’s a send-up on religion. Those comics are shooting for a certain demographic.

But Captain Ginger, the book about cats in space, is all ages. We don’t have any swearing in there or anything that would be offensive to kids, so we’re going for the old-style comic book market there.

Are they still considered “funny books”?

Hart: Yes, that is our goal with every one of our books. We’re trying to use humor. It’s what Peyer does best, it’s what I know Cammuso does best, and it’s what I think I do best. We have simply tried to feel as though we can touch any subject and breach any social taboos as long as we are funny while we do it.

We have a phrase we like to meditate on: “Smart, good-looking and funny.”

What would you say your content is?

Tom: I think that’s a big question. It’s something an adult could read and get a kick out of. We are going to be doing comics for children at some point, but I would say what we have isn’t really it.

Actually, we have a phrase we like to meditate on: “Smart, good-looking and funny.” There’s a range of art and writing styles that are a good fit for AHOY. The comics are not all the same, they don’t feel the same, but they’re all kinda funny. And I think they’re smart and good-looking, too.

There seems to be significant stereotypes associated with comic books as a whole. How do you feel about that?

Tom: I guess there is a stereotype, but when I hear the word stereotype I think of the way comic book readers are stereotyped, like on The Big Bang Theory sitcom. Personally, it’s not something I give a lot of thought to it because I’ve reached an age where I honestly don’t care what strangers think of me, but I think the stereotypes of comics has changed. In the old days, the 1950s and 1960s, the stereotype was that if an adult is reading a comic book, that adult must be stupid. Now the stereotype is they must be geeky, nerdy, brainiacs, which is very different.

Lee recalled an encounter with an editor who said, “Don’t use any words over two syllables, and just give me a bunch of pages with action.” Is this a stereotype of the art form?

Tom: Yeah, that would have been Martin Goodman, his boss who owned the company. And that was a pretty smart way to do comics, because the pages are still and you need to keep the action going, which I try to keep things moving. There are limits to how many words you want in a panel because who wants to plow through all those words when you’re reading a comic book? So, if you ask me, he wasn’t entirely wrong.

Frank: That’s not so much the nature of my work because I specifically do comics for kids. The words are of a certain reading level. I like where I’m at, which is “Middle Grade” which is grades 9 to 12, and the kids can grasp some deeper concepts at that point. It’s a fun age group.

Hart: There is always a need for action in a comic book. In comic books, they’re like the movie, just without the budget, OK? You can imagine anything and have an artist draw it. It could be a machine that stretches from earth to the next panel, it could be anything in the world. You are not limited by budget at all with comic books, you can do anything you want. Along those lines, there’s no sense in just having one face in one panel speaking, and having another character speaking. You do need action.

A long time ago, comics were seen as the low end of the intellectual spectrum; that was always the way it was in the 1940s and 1950s. Today we have great writers. The Walking Dead started out as a comic, and now it’s one of the biggest shows on television.

What would you say your style is?

Frank: Fairly humorous, it’s a kind of humorous, friendly open style. People say I have a lot of action in my work, which I like. I like mythology-type stories, I like adventure tales, things like that.

Hart: To be honest, I don’t think we’ve been around long enough for us to claim a style.

Related: ‘Pow!’ Syracuse comic writer Tom Peyer talks childhood, career journey

Where did it all start for you?

Frank: It started by drawing comics, and seeing comics. Watching things like Popeye, reading the Peanuts comic strip, and drawing cartoons at the local newspaper. But the best advice (to budding cartoonists) I can give is just draw!

Tom: Well, I’ve been doing this a long time. Before I got into comic books, I was a cartoonist at the Syracuse New Times for 12 years. Before that I was learning to draw and I really wanted to be a cartoonist. I would volunteer and do spot illustrations for a peace group or some sort of alternative paper. What I remember is getting you, Walt Shepperd, to publish some of my drawings, but there was an obstacle: I didn’t own any good pens. So you bought me some drawing pens to use, and that’s when I started drawing for publication.

Where is it heading?

Hart: Well, that’s an interesting question. I didn’t see us becoming a giant company. I want us to be known as a small company that puts out three to four comics at a time, but they were really good comics, and that’s all we need.

What’s the best thing you ever did?

Tom: The best thing I ever did? I hope I haven’t done it yet.