Each stick takes eight months to a year to craft, and he sells them for about $350 each. For now, he’s stopped taking orders and says he’s backed up about 14 months. He attributes the increased business to the growing interest in the Native American roots of lacrosse and the 2012 release of the movie Crooked Arrows.

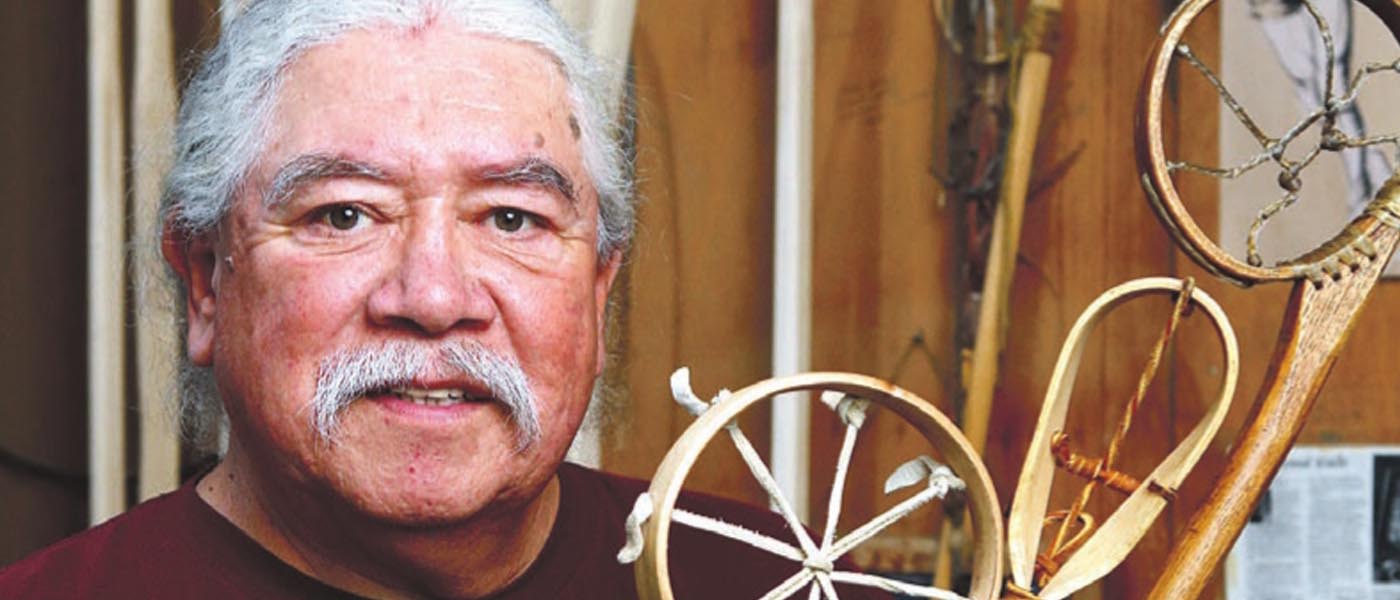

Jacques, one of a handful of Native Americans making traditional sticks, creates them from the wood of a hickory tree, and shapes, carves and dries them.

“It’s made for the game only,” he said.

“It’s not something to hang on the wall. It’s for the game of lacrosse.”

The game is so important to the Haudenosaunee that many are buried with their lacrosse sticks. “It’s said you can play the game in the spirit world with your ancestors,” Jacques said.

Jacques will demonstrate his work Saturday, Sept. 28, and Sunday, Sept. 29, at the Haudenosaunee Wooden Stick Lacrosse Expo at Onondaga Lake Park, in Liverpool. The event also includes wooden-stick exhibition games, clinics by players from the Iroquois Nationals and Onondaga Redhawks lacrosse teams, Native arts and crafts, entertainment and food and apparel vendors. The expo is sponsored by Syracuse University, the Onondaga Historical Association and Skanoñh – Great Law of Peace Center.

The purpose is to celebrate and educate people about the Native roots of lacrosse, said Philip Arnold, associate professor of religion at SU and founding director of Skanoñh, the Native American museum under development at the site of the former Sainte Marie Among the Iroquois museum.

The history of the game goes back thousands of years, to the time when the five original nations of the Haudenosaunee were warring. When they came together under the Great Law of Peace, they played lacrosse near the site of this weekend’s expo.

“Lacrosse is not a war game. Lacrosse is not a peace game,” says Arnold, author of The Gift of Sports: Indigenous Ceremonial Dimensions of the Games We Love, who has taught a course on the topic. “It’s not kumbaya. It’s a very aggressive, hard game.

Out of that energetic contest comes the knowledge of each other.”

The Haudenosaunee call it the Creator’s Game, and consider it a spiritual ceremony. Since non-Natives cannot play or watch the ceremonial games, the exhibition games at the expo will not be the spiritual version.

“We want to maintain a respectful distance from the ceremonial traditions and explain them to those who are not Haudenosaunee,” he says.

The game was co-opted by the Jesuit missionaries during the colonial era, he says. “The Jesuits saw the game being played, saw it was ceremonial and renamed it lacrosse, because the stick was like a cross,” Arnold says. Haudenosaunee call the game Deyontsiga’ehs: “They bump hips.”

Arnold’s interest in lacrosse has grown as he and his wife, Sandy Bigtree, a Mohawk, watched their twin sons play with the Onondaga Redhawks. His sons, Kroy and Clay, are graduates of Fayetteville-Manlius High School and attend Chestnut Hill College, in Philadelphia, where they were recruited to play lacrosse.

“They are very proud of the fact that they played for the Haudenosaunee,” Arnold said. “For them, this has to do with cultural pride.”

Neal Powless, a standout on the Iroquois Nationals world team and a professional lacrosse player for seven seasons, said people are increasingly appreciating the game and recognizing its roots.

“They see it’s fast. It takes agility and speed, which is why Jim Brown liked it,” he says, referring to the 1950s Syracuse University athlete who excelled in lacrosse, basketball and is considered by many to be the best running back in the history of pro football. “He could see it took more than sheer force. There’s also an elegance.”

With the right skills and knowledge, a small player can outplay a 6-foot-5 player. “That comes from the origins of the game,” he said. “It’s a gift from the creator to celebrate their skills.”

He conceded that the traditional game is rough and tough. “You can’t deny this is important to the fabric of the culture,” he says.

Even as a professional player with the Rochester Knighthawks, Powless included the spiritual aspect to the game. “When I go out on the field, I still give thanks that I can play and give thanks for the game,” he says. “There’s an innate sense this is for my heritage, and there’s a lot of pride.”

Outstanding Native American lacrosse players serve as role models for young Natives, Arnold and Powless say. The list includes Neal Powless; the Thompson trio, at the State University at Albany; Brett Bucktooth; Sid Smith; Marshall Abrams; and many more.

The lacrosse role models might also inspire young Native Americans to go to college, pursue professional sports and find careers that allow them to share their culture.

“We’re telling them, ‘You can do it, too, and you have to teach people and educate and tear down the walls.’ It gives the perception there’s a next step for Natives,” says Powless, who encourages Haudenosaunee students as SU’s assistant director of the Native Student Program.

The 2012 movie Crooked Arrows also raised the profile of lacrosse’s Native roots and boosted Haudenosaunee pride, says Powless, who co-produced the film. “Yeah, I know people say, ‘It’s Mighty Ducks.’ Two thirds of it is true, he says. “There’s that line, ‘We all win together and we all lose together.’ That’s something my dad told me.” His father is Onondaga Chief Irving Powless Jr.; a brother, Brad Powless, is also a chief.

“Now you have young people watching this movie over and over again and driving their parents crazy,” Powless said. “They’re seeing Native boys portray strong characters and who care about their culture.”

[fbcomments url="" width="100%" count="on"]