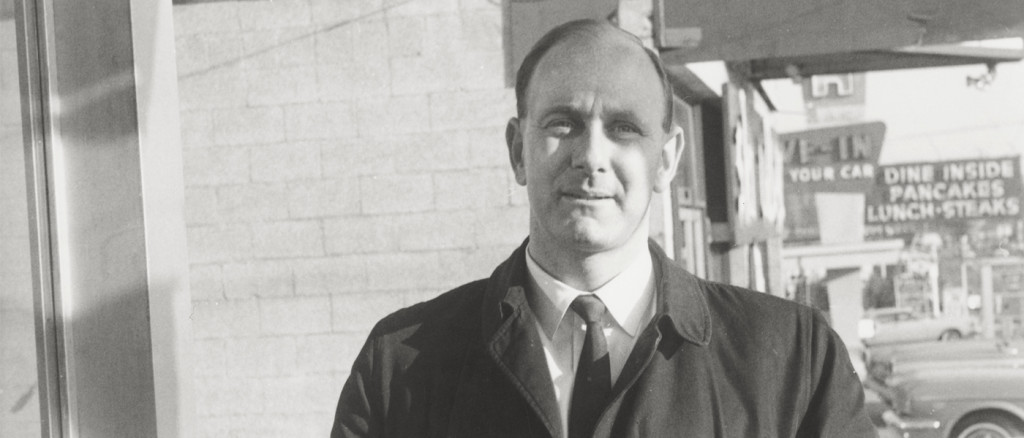

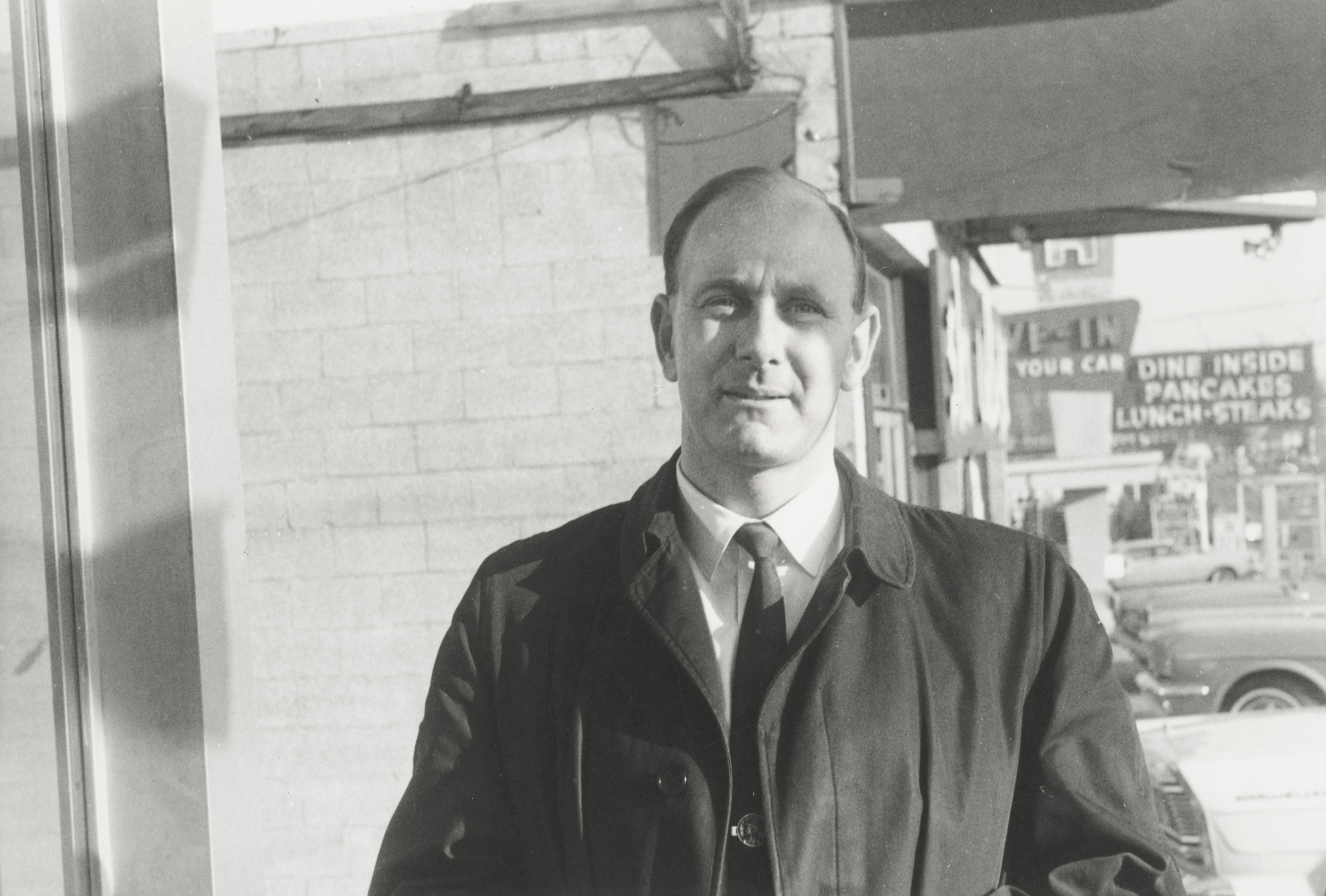

Kurt Kramer, a dispenser of kitchen table wisdom whose wisecracking style possibly influenced this columnist, has died at 86 following a stubborn battle with every disease known to Western medicine. His memorial was Saturday in Seattle.

Born Jewish in southern Germany, he and his parents narrowly escaped Hitler in 1940 and resettled in Chicago before a job transfer in the 1950s took him to the Northwest. He favored hand-knitted sweater vests and silly hats and boasted a large collection of bicycles, few of which actually worked.

Kurt was a puzzle: A tobacco company sales representative who quit smoking, an incurable teller of fart jokes who wrote love poems to his wife of 54 years, a curmudgeonly loner who could reduce a room to stitches.

He also witnessed history at its darkest.

Kurt’s father and grandfather were seized by the Nazis on Kristallnacht in 1938 and imprisoned for weeks in a test-run concentration camp. The devastating German Depression, the rise of Hitler and then his family’s struggles to build a new life in America all instilled in him a financial insecurity that bordered on the absurd. He reused teabags and Reynolds Wrap. When the family washing machine broke in the 1970s, rather than buy a new one he went to the launderette for 30-plus years.

Yet he’d spare no expense for a laugh. When he met his eldest son Jeff’s future in-laws for the first time in Skaneateles, he wore watches on both wrists. When they asked why, he replied: “One for Seattle time, one for Syracuse time.”

He lived by his own code – and to have the last word. In Chicago, an employer reprimanded him for getting his hair cut on company time.

“Why not?” Kurt retorted. “It grows on company time.”

His final two years were spent in a nursing home as dementia robbed him of his legendary head for numbers and cherished independence. Yet the ripostes continued even there. When a cognitive therapist asked him if he had any goals, Kurt replied that he wanted to be reunited with his wife, Jeanette, in her apartment.

“Can you think of any obstacles to achieving that goal?” the therapist pressed.

“Yeah,” Kurt snapped, “You.”

For all of his intransigence, Kurt played by the rules when it mattered. He served as an interpreter in the U.S. Army during the Occupation of Germany and – believing it was best for his family – he stuck it out in a pressure-packed, increasingly unpopular job as a sales representative for American Tobacco Co.

Beneath a moody, quirky exterior were deep reserves of compassion and common sense.

Those qualities were on display 1992 when this free-lancer was shot in the Los Angeles Riots while on assignment.

“We might be able to pay your medical bills, but that’s not a promise,” an editor hedged. Kurt was less equivocal. Months earlier he had quietly taken out a catastrophic medical insurance policy on his accident-prone son. He assured the hospitalized 30-year-old that everything would be fine. It was.

Kurt is survived by his wife, Jeanette; and two sons, Jeff (Leigh Neumann) and Steve, of Buzzards Bay, Mass; and four grandchildren, Miranda, Lily, Brandon and Katelyn. He also leaves behind a scrap of paper signed and dated February 2, 1971, on which he issued the following directive in the event of his passing:

Life is for the living and will go on – don’t give up, don’t grieve too long.

Remember the good times, and don’t forget the not-so-good either.

Be strong and kind to each other, be open, honest, fair … and think!

Stand up for the rights you have earned in a reasonable manner and maintain your dignity, pride and identities.

Be known as “good people.” Do the best you can to let your conscience be your guide throughout your lives. Most of all cherish family and love wisely.

Farewell, Dad. If Heaven has a launderette – and I really hope it doesn’t – may the change machine never run out of quarters.

***

Do you need a witty and memorable obituary for your loved one or yourself? Prices start at $1000. More if person is boring or unsavory. Email Jeff Kramer at [email protected]