Sitting down for coffee in a cafe on the northeastern end of Syracuse is Paul Harvey. Paul is a retired teacher and active member of our community, volunteering his time with the Historic Oakwood Cemetery Preservation Association and the Syracuse Poster Project, among other endeavors.

Born in Montezuma, New York, his path to Syracuse sits squarely in the center of many discussions surrounding the future of the community he loves. You see, Paul’s father was Eugene Harvey, the head engineer of Interstate-81, a project that has drastically altered Syracuse for the last 50 years.

Paul can remember his first time in Syracuse. His father took him for a ride through the city, visiting the areas where the highway would go. It was when he reached the 15th Ward, Paul recalls his dad saying, “My God, this is going right through the center of the community.”

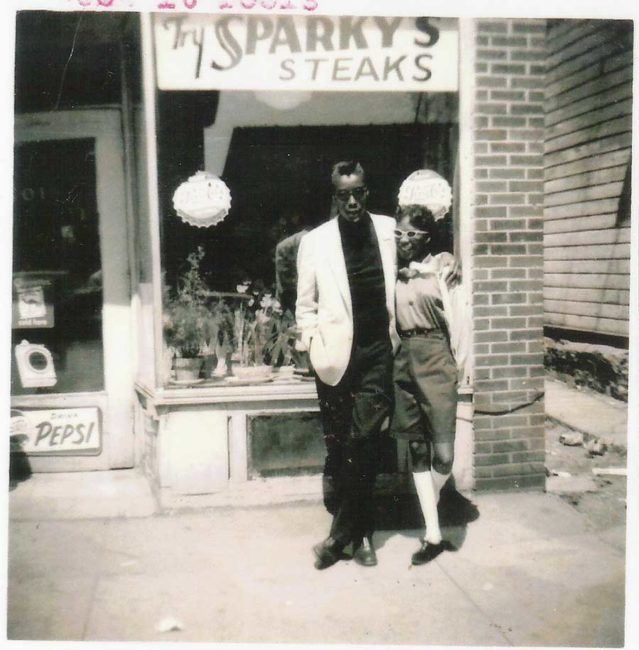

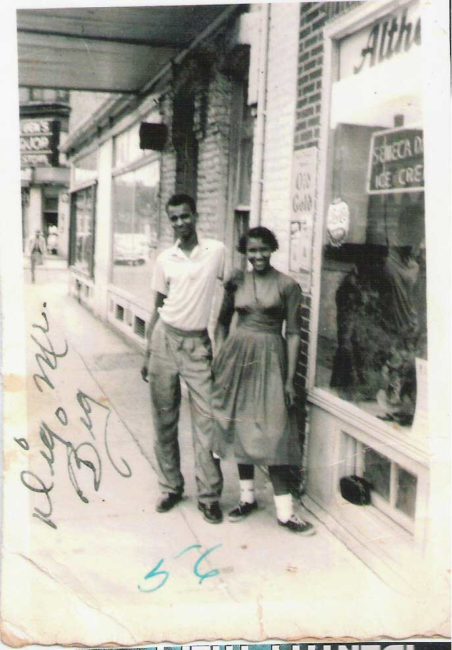

In the 1950s, the 15th Ward of Syracuse was known as the “slums.” It was an area that Dr. Charles Abrams, the New York state commissioner of rent control, told the crowd in a 1955 meeting at Maxwell Auditorium at Syracuse University, was among the worst slums in the entire world. The slums were the result of large groups of people moving tightly into geographical pockets of poverty.

After World War II, many displaced refugees and African-Americans had moved north in an effort to find work and escape the discrimination of the South. They settled in a neighborhood adjacent to downtown Syracuse. These individuals were given little to no choice in regards to housing and indirectly told where to live.

“If they sold a Negro a house in Westvale there would be the devil to pay, and the same thing goes for DeWitt.”

One Syracuse real estate agent told The Post-Standard in January 1954 his interpretation of how Syracuse real estate dealers discriminated against African-Americans, saying, “Negroes are just not shown houses for sale. We have about 700 listings that run anywhere from Fayetteville on the east to Camillus on the west. It runs from Liverpool on the north to Nedrow on the south. There is no outspoken discrimination. It is a very subtle thing. If they get a Negro who wants a house they show him a house in the slum area or the semi-slum area and tell him that’s all there is.

“Real estate dealers in this city will sell Negroes houses in the 15th Ward and its immediate area but they just don’t show houses up through the University area. If they sold a Negro a house in Westvale there would be the devil to pay, and the same thing goes for DeWitt.”

One local columnist wrote, “If the migrant worker is staying north to escape discrimination, he is following the wrong compass,” adding, “In the South they have it up in clear letters: White or Colored. In the North such signs are against the law and he often walks into discrimination blindly.”

But the opportunities in Syracuse at the time were too good to pass up. One migrant worker who moved into the 15th Ward in 1954 said, “In Florida, I couldn’t make $30 a week, I’m making $70 a week here.”

Absentee Landlords At Work

Many residential owners outside of the 15th Ward were in fear that their property values might lessen if a southern migrant worker was to move into their area. W.D. Rumsey, the East Side housing chairman told The Post-Standard that he was “definitely against Negroes living in white neighborhoods. The value of property goes down when they move in.” When asked what he thought should be done to help individuals living in the 15th Ward, Rumsey added, “I am very much interested in a plan to help them out, but human nature is human nature and you’ve just got to accept it.”

As the population in the 15th Ward continued to grow over the middle of the 20th century, housing stock and adequate housing plummeted. In 1959, there were 27,000 people per square mile in the 15th Ward, compared to the city average of 9,000.

For years, the landlords in the 15th Ward violated city codes, but went unpunished. Many 15th Ward residents lived in multi-room dwelling units that had been cut up into single room multi-unit dwelling units after previous tenants moved to the surrounding towns and villages.

One Post-Standard reporter wrote of the situation that the residents “become the prey of landlords in the area who merely put out the cardboard, split up dwellings and rent them for skyrocket prices.”

A piece written by Howard Carroll in 1959 highlighted the rental issues individuals in the 15th Ward were facing with an article titled, “Gouging Landlords Sock Tenants in the 15th Ward.” According to Carroll, the most expensive rental area in the city was indeed the 15th Ward, reporting that it cost more to live there than it did to live in the brand-new Skyline Apartments on James Street.

Countless stories of violations made their way into the local papers in the mid-1950s after The Post-Standard began interviewing occupants of the slums. The newspaper found “Six people living in a single room on North McBride Street,” “A gas leak on Cedar Street,” “11 young children living in an apartment without heat on East Washington Street,” to highlight a few.

While the area was known for absentee landlords, the paper reported, “Syracuse has yet to convict and sentence one person in connection with the violation of housing codes.” George Hebert, superintendent of the Bureau of Building and Rehabilitation said that “for every property owner in the 15th Ward who has signified a willingness to comply with the Syracuse Building Code regulations, there are a dozen who haven’t.”

Many leases forced individuals to pay rent weekly, an effort by landlords to ensure four extra weeks of rent over the year as opposed to the standard monthly rental.

Urban Renewal To The Rescue

In the late 1950s Syracuse joined several other cities across the country in an effort to redevelop what was considered urban decay by appointing a director of urban renewal. Then-Mayor Donald H. Mead hired Arthur J. Reed, who was given one major objective: slum cleanup. The answer: eliminate substandard housing. It was the belief of many public officials that eliminating the slums would bolster the demand for housing. At the time, Mead was the first mayor to take action to combat the issues faced in the slums.

City officials urged families living in the slums to seek the help of the Relocation Office, a branch created under urban renewal, as the city worked to acquire houses they deemed uninhabitable. Staff at the relocation office provided families with listings to make alternative living arrangements. During the first year in existence, one-fifth of the area’s population was relocated.

Syracuse was home to several housing projects that were constructed as early as 1939, including the Pioneer Homes, Salt City Homes and Eastwood Homes. While Syracuse seized dozens upon dozens of homes, private ownership was dwindling and new homes were not being constructed. Instead, contractors worked to create additional housing projects as residents of the 15th Ward began moving to the South Side.

While some praised the city’s efforts to combat the slums, others were more unenthusiastic. Leonard Shapiro, 15th Ward supervisor, spoke for what he considered the “displaced refugees of Syracuse,” saying, “We are talking about displaced persons who only a few years ago settled in that area because they were kicked out of other areas.” Shapiro argued that razing the slums would create an overall shortage of homes: “Where could they go out and buy replacement homes?” he asked. Shortly after his question, plans to build a 56-, 262- and 160-single dwelling unit housing projects were proposed for the South Side.

As more properties were demolished, more individuals spoke out; Rev. Walter N. Welch of Grace Episcopal Church worried that moving more large families into densely populated areas would mean more children in a section where schools were already overcrowded, negatively impacting the education of an entire generation of people.

Longtime civil rights advocate Peggy Brown stated in her 2006 memoir that “the main outflow from the 15th Ward went south, down South State Street,” adding, “where big houses were subdivided and rented.” Peggy’s husband, Frank, tried to prevent additional housing projects in the 15th Ward and pushed for land in Camillus in hopes that the housing could be truly integrated with both white and black families but was according to Peggy, “quickly denied.”

A Concrete Divide

At the same time as Syracuse was undertaking efforts of urban renewal, the 1956 Federal Highway Act authorized money for the construction of a new interstate system that would ultimately range from Tennessee to Canada.

As the new highway system was progressing ever closer to Syracuse, local officials were eager to garner their share of the funds and earmark them for urban renewal. The city also hoped to have a strong say as to where the highway might be routed near their city. Unfortunately, Syracuse was never involved in the initial planning.

It wasn’t until April 1958 that a plan leaked to The Post-Standard that the new highway would cut directly through the heart of the city, and that hundreds of additional homes, businesses and commercial properties would be affected by the acquisition of the right-of-way. When the plan was made known to the public, it was immediately rejected by the majority of residents.

New Mayor Anthony Henninger believed he had caught wind of the idea soon enough to persuade the state to change course. He told the local paper that such a highway would completely “imprison” the valuable downtown district and would prevent any further growth within the city.

Other local officials soon joined him. Carl Maar, president of the local Chamber of Commerce, said he wouldn’t support a “Chinese Wall” between downtown and the university. City Engineer Potter Kelly opposed anything that would result in an “elevated highway.” Roy Simmons, president of the Common Council, doubted that the state could “jam an elevated highway plan down the throats of Syracusans.” An editorial in The Post-Standard on April 13, 1958, pleaded for then-Gov. Averell Harriman to protect the interests of Syracuse.

From there, the discussion raged on. Two weeks after the editorial, The Herald American published an article by Joseph V. Ganley with a bold headline stating, “Stateway Elevation Fear Unfounded.” Ganley wrote that any individual worried that their property value might deteriorate due to the new highway is speaking “prematurely.”

Another article in The Post-Standard pondered the idea of a depressed highway through downtown, noting that it would “give the Medical Center and Syracuse University the prominent place they deserve in Syracuse development and provide handsomely for expansion of the central business district.” William Eagan, an executive of the Eagan Real Estate Company, stated he saw “no foreseeable development in the next 50 years in downtown Syracuse,” and any thought otherwise should not be considered for conversation.

Harry E. Lavier, secretary of the Automobile Club of Syracuse Inc., stated that smaller towns and villages were experiencing large population increases and had transformed quiet sectors into bustling suburbia. Lavier hypothesized that Syracuse would yield the same results once the highway was completed.

It wasn’t until November 1961 that the route of Interstate-81 was ultimately determined: It would be built through the center of Syracuse. To the same effect as urban renewal, the state began acquiring property from landowners for highway construction. The state provided Syracuse with additional support for relocation services as 15th Ward residents continued their move to the South Side.

The local papers were flooded with articles noting the sale of hundreds of properties to New York state and the acceptance of bids to raze structures. Among the many headlines: “Fellows Bids Low on Razing 34 Structures,” “Sale and Removal of 24 Properties,” “Building Bureau Issues 14 Demolition Permits,” “X Marks Vacant Spots Slated for Demolition,” to name a few.

Other articles in the early 1960s highlighted the demolition of dozens of properties: “31 structures on and near E. Washington, Fayette and Genesee streets,” “24 structures on Almond Street,” “29 on East Pleasant Street,” “14 structures between Clinton Street and Forman Avenue.” More than 400 properties were demolished.

Lost amid the reporting were the stories of human interest. The local papers admitted that they did little to no work in reporting on the citizens of the city during the great period of transformation for Syracuse. The Post-Standard wrote that besides a small series by Eleanor Rosebrugh, no reporter had written about the tremendous human upheaval taking place in the city, writing, “This is the sort of reporting which we must admit many newspapers do too seldom.”

Reporter Bob Driver was able to interview residents on Almond Street who, at the time, were preparing to lose their dwellings. Driver wrote, “It’s hard to find anyone who’s very excited about the highway on Almond Street.” One resident responded, “What difference does it make, the buildings have been condemned already.” A local butcher commented, “They’ll build a highway above us, and the people beneath it will keep on killing each other.” When Driver asked where a mother of four would go when the highway comes, she stated, “I’ll just hope I can get into public housing somewhere.”

By 1963, many residents were fed up with the state’s process to purchase their home. Robert Sherwood of Leon Street told James Cosgrove of The Post-Standard that he had packed his belongings more than a year ago in preparation for the move, but never heard another word after the state engineer visited.

Related: Satire | News from the year 2040 on Syracuse’s community grid

It is very plausible that this individual was Paul Harvey’s father, Eugene. Paul had stated that when his father knew of a home that was cited for demolition, he often visited with the residents to ensure they had a plan and knew what was coming. Paul said the idea of relocating thousands of citizens “hurt his father deeply,” but that his father knew if someone was to complete the project, “it might as well have been someone who cared.”

The long, tortuous process for building the highway through the middle of the city was difficult. The state ran into resistance from property owners who felt they were not being offered a fair price for their property. Other residents complained that they couldn’t plan a new housing arrangement without payment for their current home. Riddled with new laws, additional procedures, restrictions and tax relief clauses, eminent domain dragged on for years.

Some city officials advocated saving whatever they could of their neighborhoods. In January 1964, Fourth District Councilman William S. Andrews opposed closing part of East Raynor Avenue for the highway and asked for more transparency and public hearings. Then-Mayor William Walsh and the Common Council asked for more time to review the impact on downtown businesses. Shortly thereafter, state Sen. John H. Hughes expressed his “disappointment” at the snail’s pace of Interstate-81 within the city and urged the completion of the project within 18 months.

By 1966, much of Interstate-81 had been completed and was in operation. The impact was immediately seen on South Salina Street, where residential and mixed-use buildings were quickly rezoned for gas stations and drive-in services.

Carol Ehrsam of The Post-Standard spoke to John C. Louise, who owned a grocery store on South Salina Street; Louise stated the new highway “hurts my evening business because people on their way home go right past on 81. There’s much less traffic and it is quieter.” Another couple on South Salina stated they could no longer sit on their front porch because “the trucks were so loud we couldn’t hear ourselves talk.” “It’s killing us,” said motel owner John Neri. Diner owner Gerry Kosnetatos said his business had fallen 60 percent, “I hope I survive,” Kosnetatos said.

History Repeats Itself?

It has now been more than 50 years since the interstate highway was built in the heart of the city of Syracuse. The impact of the highway and the resultant suburban sprawl on the area is well documented in scholarly studies and literary articles.

Through it all, the city of Syracuse still stands, bruised and beaten, but tasked with making another gigantic decision regarding Interstate-81.

The lifespan of the 1.4-mile stretch of the highway that was built in the middle of the city has come to an end. New York state will soon decide to either rebuild the highway, remove the highway and replace it with a community grid or remove the highway and replace it with a tunnel.

Much like before, community leaders, businesspeople, politicians and residents wrestle with the pending decision. And as it was said in 1962, “A person moving away from Syracuse this spring and returning in six or seven years will hardly recognize it as the same city.”

In early 2019, the state transportation department will issue its draft environmental impact statement, a document that will kick off a 45-day comment period, after which state officials will issue a final statement that identifies the preferred option. Readers should utilize that period to educate themselves on the options and assist in making a decision. This is the second most important project our community will have ever undertaken. You just read about the first.

As Post-Standard writer Eleanor Rosebrugh told readers as the plans for the new highway were first unfolding in 1961, “Every citizen has a choice. He may let things happen to him and others. Or he may join hands with his neighbors to help plan the changes which will affect their lives.”

David Haas owns and operates @SyracuseHistory on Instagram.

More Resources

To learn more about the ongoing debate surrounding Interstate 81, consider the following resources:

- The I-81 Corridor Coalition, a group aiming to improve the efficiency and safety of both passenger and freight travel through the area

- SaveI81.org, a coalition of residents, public officials, business owners and more who oppose the proposed community grid option and want to see I-81 remain a viaduct or tunnel

- The Department of Transportation website, where various historical reports and environmental studies surrounding I-81 are published

- ReThink 81, which opposes the viaduct and wants to create a better way to improve accessibility through the Greater Syracuse area.

- The Syracuse Suburbs for the Grid Facebook group, a community group in support of the community grid option. Members of the group compile and share local news surrounding I-81, national think-pieces about community grids and meeting information from other like-minded organizations.