Herb Gardner’s I’m Not Rappaport won a surprise Tony Award at its New York City opening in 1985 and was once a staple on local floorboards but has been absent for nearly 20 years. The failure of the 1996 film version with the formidable Walter Matthau and Ossie Davis reminded audiences that the dialogue can only be done live.

Candidly, the Redhouse Arts Center’s current revival (running through Sunday, March 24) is to reunite actor pals Fred Grandy and Ted Lange, who have not been seen together since the cancellation of TV’s The Love Boat decades ago. Nothing wrong with that. The venture is considerably more impressive than last year’s On Golden Pond because Grandy plays so wildly against type. We did not know he had it in him.

Originally a cartoonist, Gardner was once known for the strip Nebbishes. He first made waves as a playwright with the autobiographical A Thousand Clowns in the 1960s and then began to look like a one-hit wonder. Rappaport, filled with the kind of games-playing dialogues that can be used in acting classes, drew on both earlier enterprises and set his sturdy reputation. Despite a few dated references — the Cold War was still a daily concern and there were no cell phones — the games and the gags freshen up spectacularly.

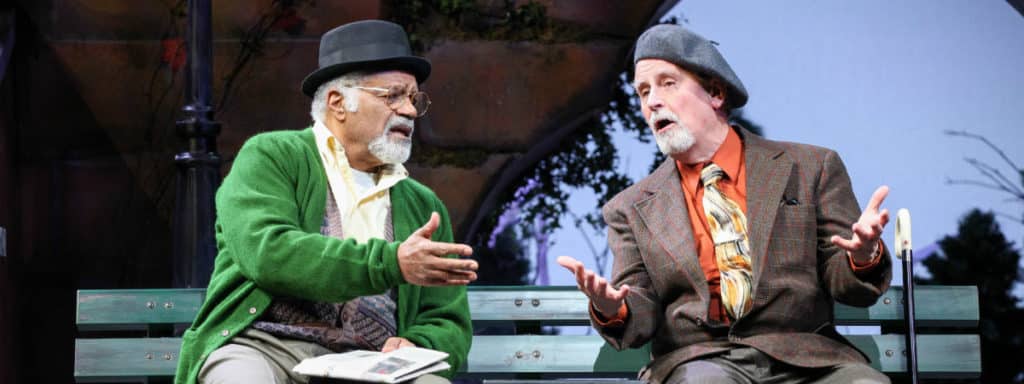

Two elderly men, one white, one black, sit on park benches in New York City. We know it’s Central Park because Tim Brown’s well-appointed set design includes one of those imposing, distinctive stone bridges, allowing joggers to pass above and painters to sketch without necessarily intruding on the action. The men are contenders rather than soul brothers.

Related: ‘Love Boat’ stars Fred Grandy, Ted Lange recall their long careers

The black elder, Midge Carter (Ted Lange), is an 81-year-old apartment maintenance man who’s losing his sight. He pretends to read the paper without always knowing which end is up. He barks at the white guy, saying he’s not been listening to anything else he says because he’s tired of all the put-ons.

Nat Moyer (Fred Grandy) identifies as Jewish and speaks with an accent and tempo evoking the late Myron Cohen. In his opening yarn he tells Midge that he is a spy chosen by the government to pose as an escaped Cuban terrorist. But wait, Nat never sounds Spanish. Midge escapes from this one quickly. More snares will follow.

We can wait for those snares because the two leads are giving us so much fun. After his TV show, Grandy was elected to Congress as a Republican representative from Iowa and after that was a voice on conservative talk radio, not to mention that he looks Protestant. Some Gentiles playing Jews can be unsettling, like Anne Bancroft in the 1988 movie adaptation of Torch Song Trilogy, but Grandy has not only timing but also the mordant lefty undercurrent. He hangs out at the Socialists’ Club. It’s not an exaggeration to say there’s a bit of Philip Roth in his Nat. If the show were on the vaudeville circuit, as is, it would be a hit.

Ted Lange has actually had a more sustained career in show business than Grandy has, and was rewarded last year with a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame. Gardner may have given Nat more lines, but when Lange is on he is certainly the co-star, sometimes getting the upper hand in the exchanges. There’s a Punch-and- Judy give-and-take that’s as much fun as Gardner’s words.

On top of the badgering tension between the two men, there are other things to worry about. At the time the play opened many middle-class New Yorkers shunned Central Park for fear of crime. Both men know they are vulnerable, and Midge has decided to pay off a prospective mugger, Gilley (Ryan Dunn), for safety’s sake. We don’t need Nat to say, “Uh-oh,” and that larger threats are foreshadowed.

A more upscale thug seems more likely to upset Midge’s world. His name is Danforth (Redhouse veteran John Bixler), and he’s about to turn the apartment house into a condo (commonplace in the 1980s) and push Midge out the door. In defense, Midge argues that only he can handle the building’s ancient furnace and that none of the directions are written down; they’re only in his head. Danforth replies assuredly that new technology will supersede all of that.

While the first act was a nearly seamless progression, the second breaks into parts dominated by new characters. One is the arrival of Nat’s daughter Clara (Laura Austin) from the posh suburbs. He disparages her abandonment of her radical upbringing. She complains, “At age 10 most kids expect to get a bicycle, and I got a copy of Karl Marx’s Das Kapital.”

Austin is fully in command of the character’s slippery emotions. Despite her semi-estrangement from her father, she’s really concerned about him. And while fundamentally admirable, she does not understand him as well as Midge and we do.

She offers him three ways to get out of his current situation, all outwardly benign and plausible, yet Nat recoils to contemplate. This leads Nat to spin out yet another fantasy, the riskiest of the script. This one is intended to forestall his daughter’s plans and drive her out of his life.

Other threads remind us of the dangers in the park and that appearances are deceiving. They include a seemingly angelic art student Laurie (Marguerite Mitchell) and a John Wayneish character wearing a cowboy hat (Ashley Strand).

Director Vincent J. Cardinal holds an endowed chair at the University of Michigan and has been a Redhouse favorite from the old theater to the new, from The Little Dog Laughed to Grandy’s Redhouse debut in On Golden Pond. In his capable hands, Nat fantasies are spun in gold.