Dinosaur Bar-B-Que co-founder John Stage has outplayed the George Soros conglomerate. Or at least he outlasted it.

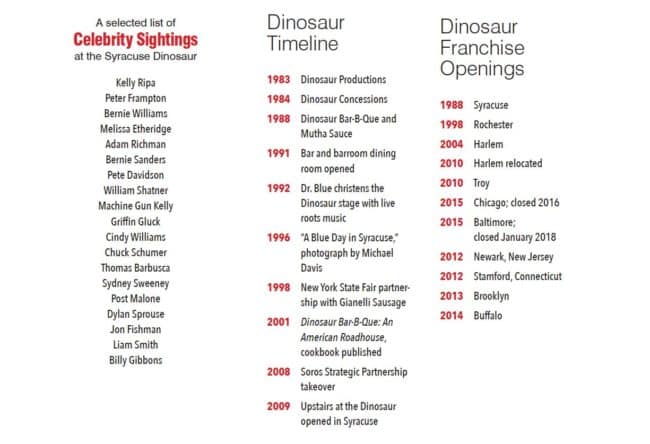

Last month, as he celebrated the 30th anniversary of Syracuse’s sauciest restaurant, which he co-founded here, Stage announced that he’d amicably ended a nearly decade-long partnership with Soros Strategic Partners, part of Soros Fund Management, LLC, an investment management firm said to be worth $30 billion, making it one of the most profitable companies in the hedge-fund industry.

“I feel like I’m back in the game,” Stage told the Syracuse New Times. “Something went right with the universe.”

Stage now owns about 56 percent of the Dinosaur, a multifaceted culinary concern that grew from an express takeout joint at North Franklin and West Willow streets to include eight restaurants across the Northeast, a line of bottled sauces and rubs, retail food packages, fiery fabric merchandise and a best-selling cookbook. These days, the Dinosaur employs some 900 cooks, servers, bartenders and office staffers across the Northeast.

Stage shares co-ownership with Fresh Hospitality, a Southern company that now owns 30 percent of the Dinosaur. Longtime local investors remain as partners, including I. Stephen Davis, who makes Gianelli sausage, and Andrew Boucounis, who owns Andy’s Produce, and the eight managing partners at each restaurant also have a stake in their locations. Syracusans Nancy and Larry Luckwaldt, who came on board in 1990 to help capitalize the Dinosaur barroom, also maintain a small percentage.

The Soros partnership started in 2008 when Stage befriended David Wassong and Mark Pinho from Soros Strategic Partners in New York City. After the Luckwaldts sold many of their shares to the conglomerate it soon took over majority ownership just as the Dinosaur was expanding into other markets.

When Soros bought in, Stage still owned 25 percent of the action and had a say in most operations. But he no longer ruled the roost.

Although the franchise generally thrived during its Soros years, it also suffered a few setbacks which Stage attributes to “an accelerated growth period.”

Perhaps prompted by corporate ambition, more than a half-dozen new Dinosaur locations opened between 2010 and 2015. Two of those seven new sites — restaurants in Chicago and Baltimore — shut down within a few years. “It was too much too soon,” Stage says.

Stage, now 58, has been taking time recently to reflect on the passing years while looking forward to the future. And while the Syracuse restaurant may be celebrating three decades, Stage insists on delving deeper.

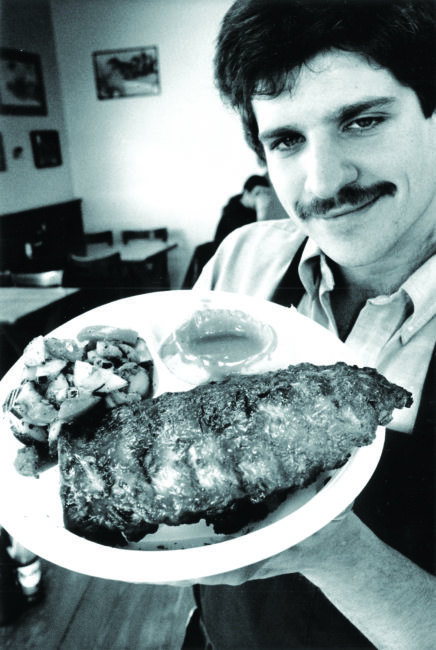

“Actually it’s 35 years, when you count the road stuff,” he said, referring to those first few years from 1983 to 1988, when it was just him and his partners Mike Rotella and Dino (pronounced Deen-O), who demurs when asked to share his last name. So 35 years ago, motivated by the lack of good food at biker gatherings such as the annual Harley Rendezvous near Albany, the threesome sawed a 55-gallon oil drum in half length-wise, borrowed some secondhand restaurant equipment and hauled that jerry-rigged gear up and down the East Coast behind their howlin’ Harleys. At each destination, they grilled burgers, steaks and sausages.

Dino — who dropped out as a partner in 1985 but has returned to function as Syracuse’s friendliest bouncer — maintains that the road-weary Dinosaur Productions was named after him despite the pronunciation difference. Stage doesn’t dispute Dino’s claim. After all, the bossman said, “Dino was an original partner and a big SOB to boot, so that seemed to fit.”

But two other factors contributed to the monstrous moniker. One was the fact that John, Mike and Dino each rode “prehistoric” bikes. Stage owned a 1957 Panhead, Rotella had a 1967 Triumph and Dino rode a 1955 Flathead.

“Then there was a Hank Williams Jr. song called ‘Dinosaur’ about a guy who revisits his favorite honky-tonk only to find, much to his chagrin, that they had turned it into a disco,” Stage said. “We could definitely relate.”

In 1984 they changed the name to Dinosaur Concessions and started working state fairs and regional festivals, still serving three basic sandwiches — Italian sausage and peppers, hamburgers and sliced steak — and occasionally chicken. The following year, Dino moved to Arizona while Stage and Rotella perfected their own original slathering sauce, which they dubbed the “Mutha Sauce.” So they changed the business name again, this time to Dinosaur Bar-B-Que.

But the constant roadwork took its toll. “During our midnight rides, our conversations kept turning toward owning our own joint,” Stage remembers. In 1987, they found “the perfect place”: the old N&H Tavern, a shot-and-beer bar operated by the late Tommy Hrim and frequented by bus drivers, cabbies and newspaper reporters. “The N&H served good home cooking and was located under the local motorcycle shop,” Stage said. “It was beautiful.”

Stage and Rotella and their skeleton crews remained on the road in order to fund the remodeling needed at the N&H. One afternoon in Hagerstown, Maryland, an elderly Southerner asked them why they called their food Bar-B-Que. “Sure, he’d enjoyed his Delmonico steak sandwich with our special barbecue sauce on it,” Stage recalled, “but he said that wasn’t real barbecue.”

No, the interloper explained, real barbecue was cooked slowly over hickory-wood fires in open and closed pits. For Stage, it was an epicurean epiphany!

“It hit me that Mike and I were just two guys of Italian descent from Central New York,” Stage said. “What the hell did we know about real Southern barbecue? The more this good ol’ boy went on, the more intrigued I became.”

So Stage kick-started his Panhead and headed South. Starting in the Commonwealth of Virginia, Stage rolled on to North Carolina, Mississippi and finally Memphis, Tennessee, which he calls “the Shangri-la of barbecue.” There the Yankee pilgrim became a total convert to the Dixiefied process of slow-smoking meat in a hickory-wood-fired pit.

Stage’s culinary conversion to “true-blue barbecue” would pay off plenty in the long run, but it didn’t happen overnight. He and Rotella — who has since retired to Florida — opened the place on Oct. 11, 1988, as the single-room, cafeteria-style Dinosaur Bar-B-Que Express. The partners kept dreaming the dream even though business remained excruciatingly slow until 1990 when the Luckwaldts joined up to open the second room, the barroom. Stage and Rotella tore out the old N&H bar and installed one that had previously done business at Farone’s restaurant on the North Side. The first house beer was Ape Hanger Ale by Middle Ages Brewing, and the first dinner special was Not Your Mama’s Meatloaf.

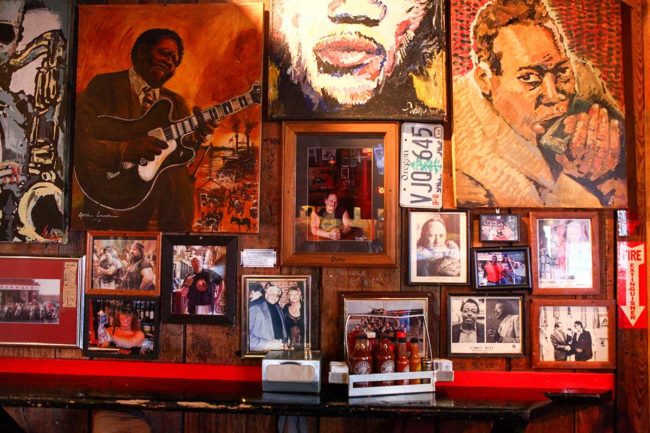

Hip nostalgia set the scene as the interior walls of the Syracuse Dinosaur are busily bedecked with performance posters, rusty license plates, musicians’ photos, bawdy B-movie lobby cards, paintings of classic blues greats by George Frayne (a.k.a. Commander Cody) and iconic offbeat murals created by Syracuse artists Jeff Davies and Elliott Mattice. And Stage remembers the first image he hung there: a humble charcoal portrait of a Native American girl still visible high in the southwest corner of the front dining area.

The ambiance was awesome, and its soundtrack was American roots music. Synchronicity smiled on the Dinosaur one Thursday night in 1992 when Kelly James a.k.a. Dr. Blue played a live set, and the burgeoning Syracuse blues scene had a new place to call home. Live music is booked six and sometimes seven nights a week, showcasing top-notch local and touring blues acts.

When the Syracuse New Times decided to celebrate the city’s blues scene in 1996, it invited scores of local musicians and roadies to pose for a classic photo inspired by Art Kane’s 1958 jazz photo, “A Great Day in Harlem.” The photo shoot for Michael Davis’ “A Blue Day in Syracuse” took place in front of the Dinosaur on the evening of June 17, 1996. It was published July 17.

The marriage of blues and barbecue turned the Dinosaur into the place to be for everyone from citified yuppies to tattooed outriders, from jocks to jerks, from South Siders to suburbanites, from lawyers to losers.

And the rest is history.

“You’ve got to remember that we started this whole thing back then when there was no internet, no barbecue cookbooks and barbecue was served exclusively below the Mason-Dixon Line,” Stage said. “Now in Brooklyn, there are seven barbecue joints within a one-mile radius. I’m sure we’ve influenced a few.”

Two years ago, Stage and former Dinosaur employee Paulie Messina opened Apizza Regionale, at the former Mimi’s location across the street from the Syracuse Dinosaur. That project “rekindled my love for the restaurant business,” Stage said. “It was fun again.”

And as Dinosaur’s majority shareholder now, he’s having fun again with the Bar-B-Que chain. “Right now, it’s all about looking inward,” he said. “The biggest thing is the culture.”

Business experts define “culture” as a texture, a vibe, the heartbeat of a company. It’s something that lights up the entire system.

“Our culture is our people,” Stage said. “That’s our special sauce! Our people are invested. I feel it personally. They feel it personally. We found that the restaurant biz was a lot like a Broadway show. When the curtain goes up, you better be ready. Our wait staff brings the show to the table. . . having fun and mingling with our customers. Our staff feeds on the down-to-earth, real-life vibe of the joint.”

And so do those hungry customers!