The “alt” in alt-weekly stands for alternative. In the first 10 years of the Syracuse New Times there was no question what we were an alternative to. The then- Newhouse newspapers, under pugnacious publisher Stephen A. Rogers, dominated political and social discourse in town. Indeed, it was to counter the malign behavior of what we used to call “the dailies” that I first became involved with our own now half-century-old alt-weekly.

The Herald-Journal, the now-extinct afternoon daily, had run a series of attacks on the English Department at Onondaga Community College, of which I was then a member. The focus was on a fresh-faced, untenured assistant professor named Thomas McKague, then in his first semester. He had assigned an essay titled “The Student as Nigger” for analysis in freshman classes. Written by Jerry Farber, an English professor in San Diego, the essay had been kicking around for five years and had been a staple in freshman classes in hundreds of schools. Taking a familiar position in the 1960s, it argues that students should not be passive when manipulated by institutions.

People at the Herald, specifically columnist Mario Rossi, hardly objected to the N-word, and if writing today, Farber, who’s still alive, certainly would have employed different rhetoric. The sanctimonious Rossi, who also often wrote favoring censorship, was a constant derider of what was then the youth culture. He seemed to take the call for student assertion as an affront to the taxpayers and to decency. His columns, however, gave no indication he had actually read Farber.

The vilification of McKague came at a time when OCC could not catch a break with the dailies. Rogers was quoted in public as having called the place “comedy college.” His animus no doubt had many sources, but one was the college’s abandonment of the old Smith-Corona typewriter factory on Water Street and building a new campus atop Onondaga Hill, occupied for the first time that semester.

The editors of the Syracuse New Times were happy to publish my words under the title, “Herald and OCC Feud Over Academic Freedom,” in the Oct. 26, 1972, issue. It wasn’t enough to point out that Farber had more in common with Mark Twain and H.L. Mencken than with Karl Marx or Ho Chi Minh. The larger point was that McKague was a professional who had every right to assign what he saw fit, what would do best to engage and motivate students. The speed at which the word got out was a lesson to me about how many people, especially influential people, read the “free” newspaper.

In The New Times piece I referred to Mario Rossi as the “Herald’s anti-intellectual in residence.” Looking back at him from 47 years, however, he is not without redemption. He was the first public figure I know of who railed at how the two interstate highways, 81 and 690, had diminished Syracuse civic life.

Some staffers at the Syracuse New Times delighted in the dailies’ frequent blunders. Clippings of misspelled and incomprehensible headlines decorated several writers’ work stations. We had the feeling that the dailies would do what they could to avoid citing the name New Times in print. To counter this, publisher Art Zimmer from 1985 to 2010 managed to rename an auditorium at the New York State Fairgrounds as the New Times Theater that would oblige the dailies, then only The Post Standard, to cite our name in events listings.

In my case there was never any personal beef with the Post or the Herald. I genuinely liked and respected many people who worked there and even got on well with the usually scowling and private Joan E. Vadeboncoeur, heiress of E.R. “Curly” Vadeboncoeur who once ran the whole shebang. I also knew they paid attention to us. Because I had been a judge of the local Spelling Bee, I was once invited to walk through the editorial office, still on Clinton Square, on a Wednesday afternoon. That week’s issue of the Syracuse New Times was mostly covered with orange ink. It was easy to see a copy on every desk.

For two years in the 1980s, when The New Times was at low ebb, I wrote for both the alt-weekly and the Post. I considered my fellow scribes and the man who made assignments to be pals. Overall, however, the experience was dispiriting. Not only would my reviews be shortened at the last moment by a few paragraphs, but they were regularly dumbed down. Particularly irksome was the deletion of “hamartia” in describing tragedy and replacing it with “tragic flaw.” In freshman literature classes I had spent about 20 minutes explaining why “tragic flaw” is a mistranslation of “hamartia.”

At the Syracuse New Times I could be free to say what needed to be said. This could mean quoting the blue language of a David Mamet play. Sometime in the 1990s I wrote the word “ensorcell,” which means to enchant in a negative way. It has no good synonym; “bewitch” won’t do it. As a longtime reader of folklore and traditional literature, I came across it all the time and did not think it especially highfalutin.

The next time I ran into Robert Moss, then Syracuse Stage’s artistic director, he greeted me with a hooting, “Ensorcell!” But within the next two weeks Maureen Dowd used “ensorcell” in one of her New York Times columns. Since then she has used it about three times a year, perhaps because malicious enchantment comes up on her beat more often than it does mine. She and her editors think Times readers can deal with it.

And that’s what we think about Syracuse New Times readers.

Defining the Alt-Write: Longtime writer reaffirms differences between the downtown daily and our alternative weekly

By

Posted on

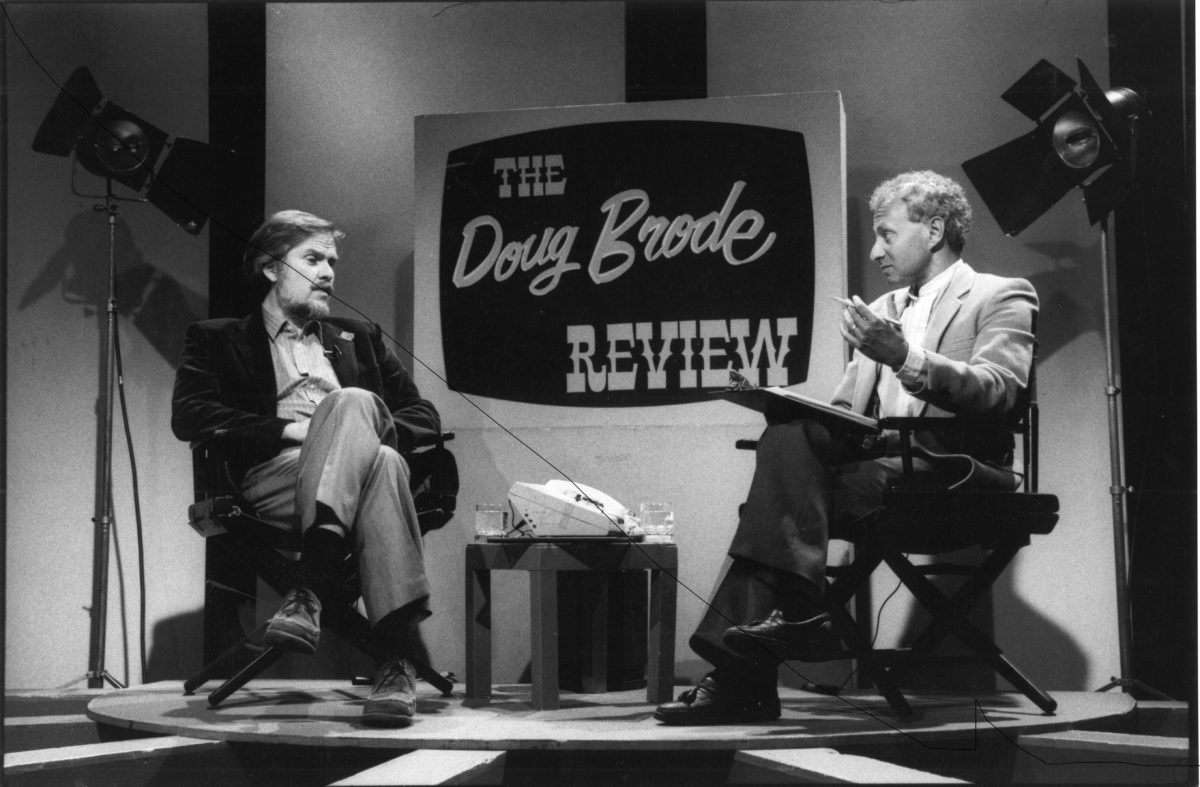

Stage critic James MacKillop trades banter with the host of The Doug Brode Review from February 1989. (Michael Davis/Syracuse New Times)