What a thrilling week for Americans. The struggle for gay rights — not limited to the right to marry — in this country has been long awaited, and public opinion changed almost instantly over the course of just a few years. One question that is often asked, usually in hindsight, is whether politicians or activists deserve the lion’s share of credit for changes. It’s the old hope vs. change question.

Seeing that America is a republic, the voting process is undoubtedly an essential part of the equation. Perhaps taken more for granted are those who bravely stand against public opinion in a way which is moving, inspiring and too often thankless. In June, 1974, such an event occurred in Syracuse when the first “Gay Pride Field Day” was held in Thornden Park.

The event was organized by the Gay Freedom League, the first group of many who put their time and reputations on the line to make their city a great place to live. Sponsored by Syracuse University’s Hendricks Chapel, the GFL provided information and support with a library and phone line, known as Gayphone.

That day, people — gay and straight — gathered in the park, much as they do now, to eat, drink and be merry. It was a strange combination of openness and wariness. A sound system blared dance music, no doubt drawing attention to the crowd, but only three people used their full names (Bob and Harry Freeman-Jones and Bonnie Strunk), and some teachers wore paper bags over their heads to avoid being fired from work.

According to Earl C., who became a leading gay rights activist in Syracuse, the celebration was going on just fine until some teenagers began to throw rocks at the crowd. Incredibly, Channel 3 news arrived to cover the event and began to film the “stoning.”

Earl became irate with the way things were coming together — this was not the way the day had gone. He confronted the black reporter, Johnny Bowles. Surprisingly, Bowles agreed and offered to interview Earl on camera.

“It was a hard choice, but truly, I had no choice. Earl C. became Earl Colvin and came out on the Channel 3 6 o’clock news.”

Colvin was fired from AGWAY the next day, but he still viewed it as the right decision. At the time, employment discrimination was banned only in certain cities in New York. His characteristic sense of humor intact, he would later joke that when he one day owned a business he would fire employees because they were straight.

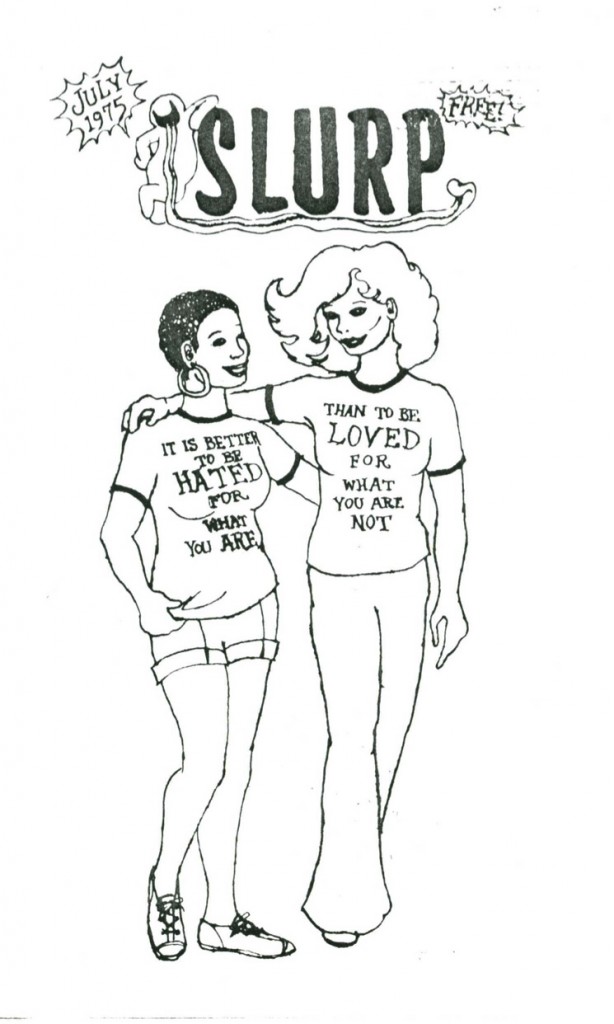

Later, he and his partner Joe Rinne would print a newsletter called Syracuse Lavender Union Reporting Press, or SLURP. Subscribers to SLURP, which included entertainment and political reporting, were kept confidential.

Twenty-two states (plus D.C.) and as many as 500 localities prohibit employment discrimination based on sexual orientation. However, federal law has yet to catch up. Change comes in fits and starts, but relies on people — not just politicians — to inspire hope as well.

Earl Colvin died this past May before the Supreme Court decision was made. Judging from tributes from his family and friends, his life, full of creativity and courage, will not be taken for granted.

For more information on the fascinating history of the Gay and Lesbian movement in Syracuse, see the Chad Wheaton Papers at the Onondaga Central Library.