Music writer Russ Tarby on the history of the Syracuse Area Music Awards, which keep on truckin’ after 17 shows over 22 years

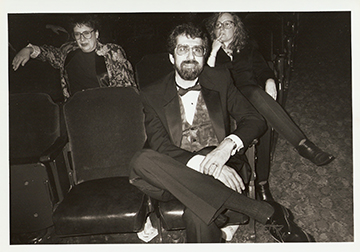

More than two decades ago, four lovers of local live music, accompanied by a bottle of plum wine, gathered at Sakura, Mrs. K’s intimate sushi-and-jazz club on West Fayette Street. Led by Syracuse Jazz Fest founder Frank Malfitano, at the time the executive director of downtown’s Landmark Theatre, the quartet included graphic artist Sue Lunn, Herald-Journal music writer Brain Bourke and me. At the time, I was the music and events editor at the Syracuse New Times.

Our mission? To brainstorm the creation of the Syracuse Area Music Awards, nicknamed the Sammys.

Between sips of sweet vino, the ever-loquacious Malfitano –a reputed teetotaler– waxed eloquently about his idea to honor the musicians who elevate our community’s quality of life. Brian and I raced to compile long lists of potential honorees and hall-of-famers. We debated the pros and cons of various awards-show formats and musical categories. Sue Lunn sketched logo ideas, including a never-used image of a salt shaker with its contents pouring suggestively through its cap’s tiny holes.

“I hatched the idea in 1991,” Malfitano remembers. “I spent three years raising $30,000 for the first edition of the Sammys. For the launch, we wanted to make sure it came out of the gates in a big way because, as Will Rogers said, ‘You never get second chance to make a first impression.’”

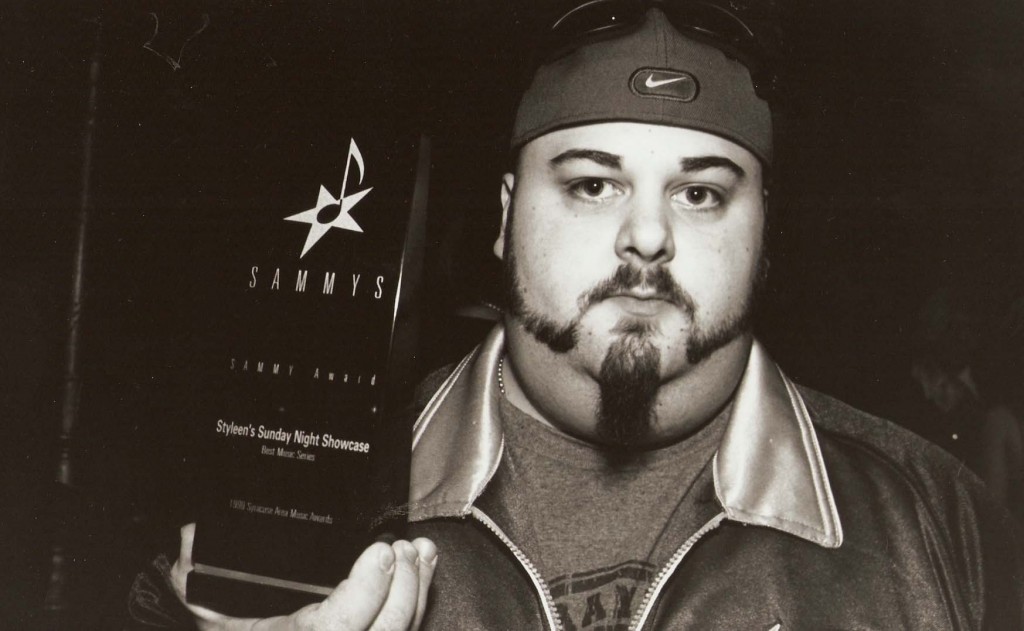

Michael Davis Photo | Syracuse New Times

Malfitano already had experience running music events. He had christened the Syracuse Jazz Festival in 1982, and over that decade he worked in the jazz biz in Manhattan and Washington, D.C. In summer 1990, he was hired to helm the Landmark.

“I had three goals at the time,” Malfitano remembers. “I wanted to put the Jazz Fest downtown and make it free. I wanted to establish the Sammys. And I wanted to create a Syracuse Walk of Stars. The purpose of each goal was to elevate the profile of Syracuse musicians and artists and give them the recognition that had been previously lacking in the community. For the Sammys, I envisioned a great show at a great venue with great production quality. I even wanted the statuettes to be significant and memorable.”

Michael Davis Photo | Syracuse New Times

So he assembled an ad hoc advisory group, including early Sammys supporters such as the UpDowntowners, led by Winterfest honcho Bill Cooper; Syracuse New Times editor-in-chief Mike “Mr. Goodvibes” Greenstein; booking agent Dave Rezak; Ron Wray, dubbed the “Syracuse Music Authority”; and local concert promoter Liz Nowak.

“Frank sent me a postcard asking if I’d be interested in joining the committee,” recalls Nowak, who became Sammys chair in 2009. “I had good contacts with people like Mark Gummer at National Audio, the radio stations and local musicians, so I was pleased to participate.”

Rock the Joint

In 1992, while Sammys plans were in full swing, the local music community was stunned by the sudden death of Bourke, 30. While biking to Nashville that summer, he was hit by a car on a Pennsylvania highway.

Bourke’s untimely death seemed to shake the Syracuse music community into action. “It’s sad to say,” Malfitano muses, “but I think the turning point was when Brian Bourke passed away. Before that, it was tough to get everyone on board. Not everyone shared my vision for the Sammys.”

The Sammys committee named the Best New Artist Award after Bourke, and that seemed to motivate production people and potential sponsors who now saw the awards as a both a memorial and a celebration of life.

“It wasn’t easy getting that Spruce Goose airborne,” Malfitano says. “But after that first edition, the subsequent shows flowed like milk and honey and butter.”

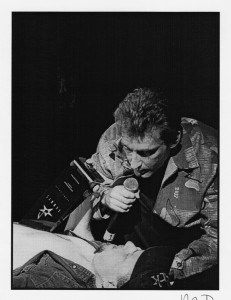

The first Syracuse Area Music Awards show finally hit the boards at the Landmark on May 7, 1993, hosted by comedian Jeff Altman, a Nottingham High alumnus. “I always thought it should be Syracuse comedians,” Malfitano says, “so I went with Jeff Altman and I brought back Bobcat Goldthwait and Tom Kenny from the Generic Comics.”

Big winners that first year were George Rossi, Joe Whiting, Stroke and the Hagan brothers, and jazz singers Ronnie Leigh and Nancy Kelly. Radio icons Dick Clark and “Dandy” Dan Leonard received Lifetime Achievement Awards, while the freshman class of Sammys Hall of Fame inductees included Jimmy Cavallo, Stan Colella, Benny Mardones, Tony Trischka and Spiegle Willcox.

“It was one for the record books,” Malfitano exclaims. “It was like a prizefight or a movie premiere, with limos and black ties, a great overture by Stan’s orchestra, Cavallo honkin’ that horn. Quite an occasion, very special!”

Hyperbole aside, the first Sammys drew a near-sellout crowd of 2,400. From the outset, Malfitano realized ticket sales would help balance the annual budget. “We knew that each of our nominees would have five or six friends and family members who would buy tickets to the show,” he said. “No doubt about it, we wanted to put fannies in the seats.”

Rhythm of the City

Malfitano ran the Sammys over its first three incarnations, in 1993, April 22, 1994 (again hosted by Altman) and April 12, 1996 (presided by the Goldthwait-Kenny tandem), when he received a Hall of Fame Award. Longtime Syracuse New Times editor-in-chief Mike Greenstein took over as chair for the Landmark’s next show in November 1997.

The budget remained at about $30,000 that year when former Saturday Night Live star Joe Piscopo hosted the 1997 event. “That number would include talent, lighting, staging, security and some theater costs,” Greenstein wrote in an email. “A lot of stuff and services were, of course, donated or severely discounted.”

Piscopo didn’t come cheap. “Talent was no doubt the biggest expenditure,” Greenstein confirms.

Sammy revenues were similarly varied. “Revenue came from sponsors (little cash, mostly in-kind donations such as graphics and space from the Syracuse New Times and various radio co-sponsors) and ticket sales,” Greenstein remembers.

Michael Davis Photo | Syracuse New Times

Musicians themselves pitched in to raise cash for the awards show. “I remember organizing and playing in songwriter showcases and some in-store gigs to raise money for the Sammys,” says multiple-Sammy winner Gary Frenay, who also served on the committee from 1992 to 1999.

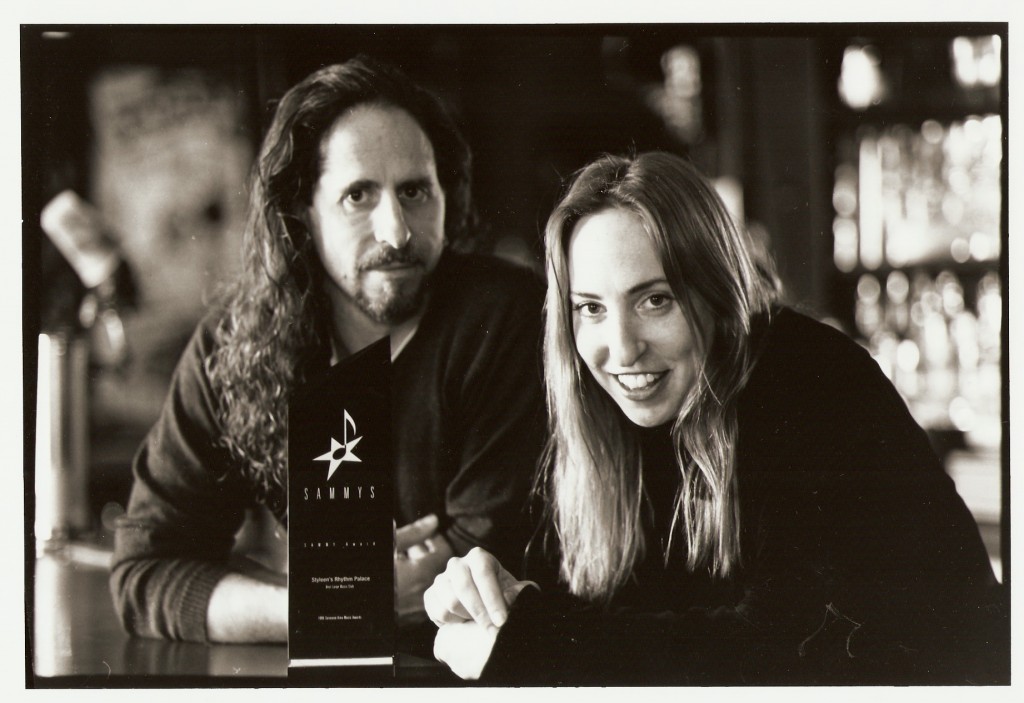

In those days, Greenstein also attended plenty of fund-raisers. “We had Sammys showcases (multi-band events in clubs), and I even recall bowling at Flamingo Lanes and my farewell party at Styleen’s Rhythm Palace both raised money for the Sammys.”

After Greenstein moved to Seattle in 1998, the chair position was filled by Gregg Gambell, an advertising rep who had ascended to general manager at the Syracuse New Times. The newspaper’s publisher Art Zimmer, and his wife, Shirley, had also been enthusiastic Sammys supporters.

Gambell may have lacked music-industry experience and was the youngest of the Sammys chairs, but somehow he and his committee put the Sammys back on its feet. Following the ceremony’s hiatus of nearly three years (the 1999 blowout was hosted by Rhonda Shear, then a popular host on the USA Network), Gambell oversaw the Sammys’ swan song at the Landmark on Feb. 1, 2002 (emceed by Moody McCarthy), then held the committee together over for another two years without putting on a show.

Listen to the Music

Michael Davis Photo | Syracuse New Times

Finally in June 2004, Gambell and company reinvented the Sammys and brought the awards show to the food-flooded Taste of Syracuse street festival, held each June in downtown Syracuse. The awards, staged every year from 2004 to 2009, were now presented outside under a tent rather than onstage at a gorgeous Jazz Age theater.

Yet partnering with Taste founder Jim Horsman was a good way to save money: With no need to underwrite paychecks for big-name hosts such as Piscopo and Shear, the committee no longer needed to raise $30K the way Malfitano did in the beginning. The overall budget had dropped to less than half that figure, as local radio personalities donated their time to emcee the show.

Before the 2005 event, Horsman sold Taste of Syracuse to Ed and Pam Levine’s Galaxy Communications, who continued hosting the Sammys for the next four years. “We had a great relationship with Galaxy,” Nowak says.

Michael Davis Photo | Syracuse New Times

In those days, state Sen. John DeFrancisco was still bringing home the bacon in the form of state tourism grants, which buoyed the cash-strapped awards show and practically every other festival in town. So Gambell quietly steered the Sammys steadily through its first half-decade before Nowak took over for the awards’ last year at Taste of Syracuse in 2009.

In other changes, the first separate Hall of Fame celebration took place in 2009 at Alliance Bank Stadium (now known as NBT Bank Stadium), then moved in 2010 to Upstairs at the Dinosaur, its current location. Meanwhile, the Sammys awards show relocated to the Pirro Convention Center for the 2010 and 2011 editions, then moved to Eastwood’s Palace Theatre in 2013, where it has regained some of its former glitz.

“Taste of Syracuse was fine for the performances,” observed six-time Sammy-winner and former Sammys board member Joe Whiting. “But trying to present the Sammys Hall of Fame and lifetime awards was kind of awkward. It’s much better now that those awards are given at an inside venue where you can actually hear the acceptance speeches.”

Michael Davis Photo | Syracuse New Times

Speaking of Whiting, early Sammys fans were made aware of the “Joe Whiting Rule,” which Joe himself had suggested, stipulating that no artist would be eligible to win the same award two years in a row. Now that the focus is on recent recordings, that rule has grown obsolete, but when it was in effect it encouraged honoring more and newer performers.

To further involve Central New York’s music fans, the Sammys has traditionally sponsored a few People’s Choice Awards in categories including Best Band, Best Venue and Best Festival. In 1993, just 165 people’s choice votes were cast via a 900 phone number hosted by the Syracuse New Times. This year, according to Nowak, more than 115,000 votes were registered online.

Meanwhile, the Sammys’ method for selecting awards had changed dramatically. In 2004 the Sammys committee replaced its popular-vote system with a gaggle of judges assigned to assess regional recordings. The Sammys now recognized a baker’s dozen recorded works, which trimmed expenses by eliminating ballot printing and lowering the number of trophies needed. For the 1993 awards show, the Sammys paid more than $6,100 for 41 statuettes.

By honoring fewer performers, the Sammys sliced its trophy costs by half.

Talk Is Cheap

Michael Davis Photo | Syracuse New Times

As with all awards shows from the Oscars to the Grammys, the Sammys has endured its share of negative press over the years. Local songwriter and radio host Larry Hoyt, for example, created a stir with Facebook posts grumbling about what he labeled a “painfully loud” sound mix at the March 2014 awards show at the Palace. Many attendees, including at least six musicians, agreed with him about the surfeit of volume.

“In retrospect, I probably went about it the wrong way,” he says, now maintaining that he should have gone directly to the Sammys committee with his observations in the spirit of constructive criticism. “I just think that since the Sammys are trying to promote the music created here, they ought to make sure that that music can be properly heard and enjoyed.”

Michael Davis Photo | Syracuse New Times

Another persistent Sammys complaint is that musicmakers have to cancel paying band jobs in order to attend the awards show–on a weekend night, no less. “Yeah, that’s the complaint I most often hear from other musicians,” Joe Whiting admits. “But what are we gonna do: schedule the Sammys on a weekday? In terms of attracting crowds (to the awards show), it’s got to be on a weekend night. It’s a special event once every year or two years, so you just gotta bite the bullet.”

Still, the Sammys committee could theoretically silence this longstanding gripe by moving its awards show to a Sunday. The Rochester Music Hall of Fame, for instance, will induct its 2015 nominees, including jazz keyboardist Gap Mangione, on Sunday, April 26, at the Eastman Theatre.

In the early Sammys years there was also plenty of moaning regarding the categories. Malfitano wasn’t surprised: “People here, including musicians and club owners, are always complaining. You gotta stay above the fray. I mean it was like herding cats sometimes, and I had to be a tough guy to keep everyone in line.”

The first six awards shows featured nominations in nearly three dozen categories, ranging from country to rhythm ’n’ blues, from blues to jazz, from best band to best vocalist.

The Sammys committee itself nominated up to five acts in each category and also determined lifetime achievers and hall of fame inductees, two of the former and five of the latter at its 1993 debut.

All members of the music industry–from stars in the spotlight to the backstage crew pushing equipment, to bartenders pouring the sauce–were eligible to vote in 34 categories. Bucketfuls of ballots came in, and counting them was an arduous task. When the ballot-vote system was replaced with a committee which judged recordings in 2004, the Sammys more closely mirrored its Grammys model.

Now there are nominations for locally produced recordings in 13 genre categories including hip-hop, alternative, Americana and singer-songwriter. “There have been category shifts and additions in response to stylistic shifts in the music scene,” notes Andrew Russo, who chairs the judging committee. “Jam Band is a new (category) addition this year, and there always is a broad Other Styles category for music that doesn’t really fit any type of stylistic label. There’s great variety among each year’s submissions. That’s what makes this event so interesting.”

Train Keep A Rollin’

Michael Davis Photo | Syracuse New Times

The number of awards is one thing, but the bottom line still has to be measured in dollars and cents. In 1997, the year after Malfitano’s last year as chair, the Sammys became a 501(c)(3) nonprofit. Its tax returns simply state that they operate under the $50,000 limit, which allows them to keep their financial information confidential.

“We’re not obligated to make our budget or other financial information public,” Nowak wrote in an email. “I’m sure you can understand that publishing the agreements we have with our venues and other vendors could result in potentially sticky situations with other groups they work with.”

So let’s estimate the Sammys’ anticipated revenues and expenditures to get a pretty clear idea of its annual budget. Considering that money is not pouring in from Albany anymore, things still look fairly rosy. That’s primarily due to ticket revenue, something that was nonexistent for the Sammys during its six-year run at Taste of Syracuse.

If the awards shows sell out, in fact, the Sammys could bring in up to $17,000. Upstairs at the Dino seats 200 at $25 each, and the Palace seats 700 at $20, so gross receipts could be $5,000 and $12,000 at each respective venue.

Of course, the venues charge rent. Upstairs at the Dinosaur normally rents for $1,000, and if the Sammys pay $11.95 per person for dinner, that’s another $2,390 for a total of at least $3,390 owed to the Dinosaur Bar-B-Que. Rental at the Palace usually goes for a grand plus another $1,400 or so for soundman Mike Angiolillo, for total overhead of at least $2,400 at the theater.

Besides ticket sales, the Sammys make money from sponsorships and donations. For the second year in a row, the Destiny USA nightclub World of Beer, which features live music most nights of the week, has bought in as Sammys title sponsor at an annual rate believed to be $2,500.

Other sponsors are invited to back the awards at the Gold level ($1,500) or the Silver level ($500). This year, there’s only one Silver sponsor, K-Mase Productions, Kathleen Mason’s Eastwood-based events company. And the Sammys website (syracuseareamusic.com) lists 14 “Friends of the Sammy,” including all of the committee members who contribute $25 each for a total of $350.

Since apparent expenses total about $10,000 and estimated income approaches $15,000 or so, it looks as though the Sammys do better than break even, and that’s good because it leaves a little financial foundation on which to build the next big show.

“We are a tiny, volunteer-run organization,” Nowak says. “We depend on the goodwill of our partners and the community.”

Who Loves You?

Michael Davis Photo | Syracuse New Times

After nearly a quarter-century, the Sammy Awards have become a local music institution. Malfitano feels that the Sammys have fulfilled his vision to elevate the status of artists and entertainers in this rustbelt burg. “I’ve seen Sammys (statuettes) displayed on people’s mantelpieces, on their desk as work, even at funerals,” Malfitano says.

“Frank was the driving force to get it going, but the dedication of Liz has kept it going,” Greenstein observes. “And without the Syracuse New Times to chronicle and promote it, it would not have happened or lasted.”

Longtime committee member Ron Wray notes that the Sammys Hall of Fame winners are especially pleased to have their entire body of work honored. “Guys like Bobby Comstock and Chris Goss traveled a long ways to be here to attend their inductions this year,” he says. “They’re excited as hell to be here.”

And consider this year’s Lifetime Achievement winner, Jon Fishman, who went from the worst drummer in the Jamesville-DeWitt High School Marching Band to the namesake drummer of Phish, the greatest jam band ever second only to the Grateful Dead.

Fishman himself says he’s a bit embarrassed to consider himself a lifetime achiever at age 50, but his dad, Dr. Leonard Fishman, can barely contain his paternal pride. “Dr. Fishman is going gaga about Jon’s award,” Nowak noted.

That’s what the Sammys is all about.

Jury Duty

(Photo: wikipedia)

For the past six years, classical pianist Andrew Russo has served as chair of the Sammys’ judging committee. Russo knows something about big-time music competitions: After studying in New York City, France and Germany, he played in the Van Cliburn International Piano Competition in 2001.

Besides Russo, this year’s judges include audio engineer Paul Bertalan, Syracuse University instructor of music James Abbott and longtime local music fan Andrew Goldberg of Fayetteville.

Russo’s jury spends many hours listening to CD submissions. Since last December, the four judges evaluated nearly 100 recordings submitted by local musicians to choose this year’s 57 nominees.

“After nominees are selected, each judge spends five or six days with the recordings, drilling deeper and ranking them in order,” Russo explains. “Points are assigned to each rank and simple math is done to get each recording’s score in each category. If there’s a clear winner, the process stops there.”

If there is a tie for first or the top two scores are very close in a category, the judges discuss finer points of the submitted work to determine a winner.

Trophy Catch

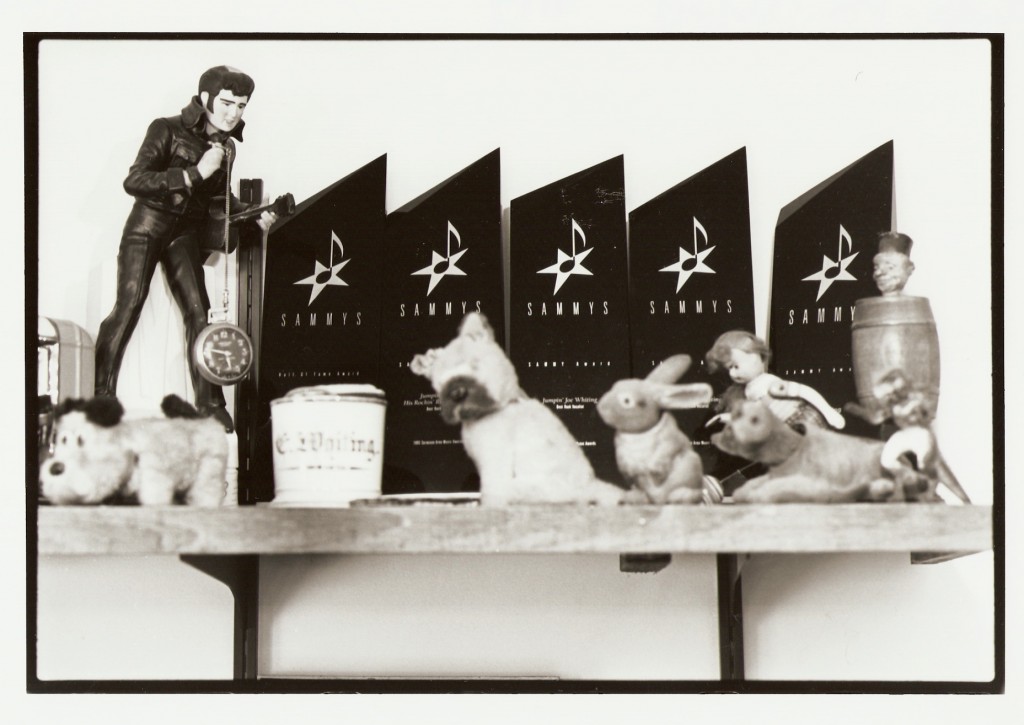

Michael Davis Photo | Syracuse New Times

The Sammys have rock’n’rolled with several alterations over the years. “The directors on the committee have changed and so have the venues and the time of the year,” says Sammys chair Liz Nowak. “But the award statuette has remained the same.”

Designed by the late David O. Chase of ChaseDesign in Skaneateles, the monolithic awards were initially manufactured in Canada but have since been produced by a U.S. firm. They cost $150 each, and the committee absorbs significant postage and handling costs to make sure they’re delivered here by showtime.

“We only give one statuette to each winner, even if it’s a 10-piece band,” Nowak said. “So if the band wants trophies for all of its members or its roadies or whatever, they can pay $175 for each additional statuette.”

Over the course of its 17 awards shows, the Sammys have awarded 529 statuettes, including 444 winning awards and 84 trophies for Hall of Fame inductees, lifetime achievers and educators.

The 2015 Sammy committee, which includes chair Liz Nowak, treasurer Debbie Foley, Carol Thoryk O’Leary, Julie Briggs, Ron Wray and Mike Donohue, selected this year’s four honorees for the Sammys Hall of Fame: Bobby Comstock, Chris Goss, Loren Barrigar and The Works. The committee also anointed Dave Rezak as music educator of the year and Jon Fishman with the Lifetime Achievement Award. The Hall of Fame awards were presented March 5 at the Upstairs at the Dinosaur Bar-B-Que venue.

The Sammys ceremony, presented March 6 at Eastwood’s Palace Theatre, yielded these winners:

Michael Davis Photo | Syracuse New Times

Best Pop: Nick & Noah

Best Country: Megan Lee

Best Jazz: Nick Ziobro

Best Hip-Hop: Nick Case a.k.a. Decoy

Best Blues: Castle Creek

Best R&B: Brownskin Band

Best Americana: Jeffrey Pepper Rodgers

Best Alternative: Leah Shenandoah

Best Rock: William Gruff

Best Hard Rock: Nineball

Best Other Style: Samba Laranja

Best Jam Band: Joe Driscoll and Sekou Kouyate

Best Singer-Songwriter: Alanna-Marie Boudreau

Brian Bourke Award, Best New Artist: Spring Street Family Band

People’s Choice, Best Artist: Briana Jessie

People’s Choice, Best Festival: Fox Fest

People’s Choice, Best Venue: Kegs Canalside

The Sammys Through the Years

1993, 1994, 1996, 1997, 1999, 2002: Landmark Theatre

2004-2009: Taste of Syracuse

(2009 Hall of Fame inductions at Alliance Bank Stadium; moved to Upstairs at the Dinosaur in 2010)

2010, 2011: Pirro Convention Center in conjunction with the Music Industry Conference

2013-2015: Palace Theatre

Memorable Sammys Moments:

Michael Davis Photo | Syracuse New Times

1993: Stan Colella’s orchestra playing a chart from 805’s 1982 hit “Young Boys” as part of the overture; Jimmy Cavallo cavorting about the stage playing sax and singing “I Want My Fanny Brown.”

1994: Legendary clubowner Bob “Cap’n Mac” McIntyre chokes up as he accepts his Hall of Fame Award.

1994: Sam & The Twisters inducted into Hall of Fame, minus Baron Daemon.

1996: Kathy Arlotta accepts for her late husband, keyboardist Larry Arlotta.

1996 Dan Elliott & The Monterays, dressed in tuxes, kick ass with a cover of Steppenwolf’s “Born to be Wild” as they enter the Hall of Fame.

1997: Saturday Night Live alumnus Joe Piscopo, famed for his Sinatra imitations, sings Jackie and Gary Frenay’s version of “New York, New York.”

1997: The Kennedys turn in a decidedly jangly, surprisingly psychedelic set.

1997: Mickey McMenamin and Terry Vickery from the BeBop Shop recreate their infamous late-night TV commercial before they present an award.

1997: At an after-party upstairs at the Landmark, Verona polka accordionist Fritz Scherz jams with Syracuse blues band Los Blancos.

1999: Styleen’s Rhythm Palace owners Mike and Eileen Heagerty reminisce delightfully about trying to gain entry before they were of legal age at area nightclubs that showcased live music.

2001: Last Sammys staged at the Landmark featured former Hall of Fame inductee Hal Casey who tears up the joint with “Orange Blossom Special” as his fiddle marvelously mimics barnyard bleatings, screeching semi-trucks and police sirens.

2006: Guitar-banger Mick Fury lives up to his name by raging against the band Muzzlestamp after they beat him out in the Best Rock category. Fury reinvents himself as a country-rocker and wins a 2014 Sammy for a record he made with his band Midnight Moonshine.

2013: Frank Malfitano returns to the Sammys to present Founder’s Awards to journalists Mark Bialczak and Molly English-Bowers.

2014: Tom Kenny reunites with his old friends, Sammys Hall of Fame inductees The Flashcubes, who perform what may have been their loudest set ever.

2015: Grupo Pagan, already a soul-stirring quintet, went over the top by adding a long line of djembe drummers and an all-star chorus singing Edgar Pagan’s life-affirming lyrics.

2015: Joanne Shenandoah vocalized a cappella songs of peace and wellness, then invited her daughter Leah to the stage to demonstrate her improbable mix of jazz, mideastern and Iroquois vocal stylings.

2015: The Ruddy Well Band delivered a fiddle-driven acoustic set, followed by the metal of Scars & Stripes and the rock bravado of The Works.

2015: Masters of Reality rock icon Chris Goss said during his acceptance speech for his Hall of Fame award, “Seattle was a dark, dreary city. So was Liverpool (England), which gave us The Beatles. Good music comes out of dark places. It comes from the heart, not the sky.”

Russ Tarby served on the Syracuse Area Music Awards committee from its inception in 1992 to 1999 when he was music editor of the Syracuse New Times.

CLICK HERE to see the 1993 – 1999 Sammy Award Photo Gallery