A GROWING PROBLEM

Police officials say there’s a glut of heroin in Onondaga County. The drug is ensnaring unsuspecting communities and taking a stronghold on youth. Use of the drug, once rarely seen, has skyrocketed across the region, sending dozens to the hospital. The city of Syracuse is the breeding ground for dealers, bringing in buyers from across the region. On any given night, police see cars drive in and out of drug-ridden areas, many of the buyers from communities where drugs haven’t traditionally been as prevalent. “Most of the people buying this drug are from outside of the city,” said Syracuse Police Lt. Daniel Belgrader. “They’re all ethnicities. They’re all ages. It’s all over the board, male and female, probably from (age) 20 right up to 50s and 60s.” He says the drug market has evolved in recent years, allowing easier access. Many drug deals used to be behind closed doors, he says, but some areas of the city, such as the Near West Side, have become “like an open air drug market.” Dealers peddle many types of drugs from one location or on their own person. In one block of the city, there’s a chance users can find it all: marijuana, crack, cocaine, meth, spike. But recently, it all keeps coming back to one: heroin. Five years ago, Syracuse police executed heroin search warrants two or three times a year; it wasn’t a common drug to see. Last year, more than 50 percent of the city’s search warrants were to find the drug. In 2012 in Syracuse, 275 grams of heroin – almost 10 ounces – was confiscated. In 2013, that number skyrocketed to the recovery of more than 1,500 grams, about 3¼ pounds, a 445 percent increase. Police say they’re on track to surpass that in 2014, by far.

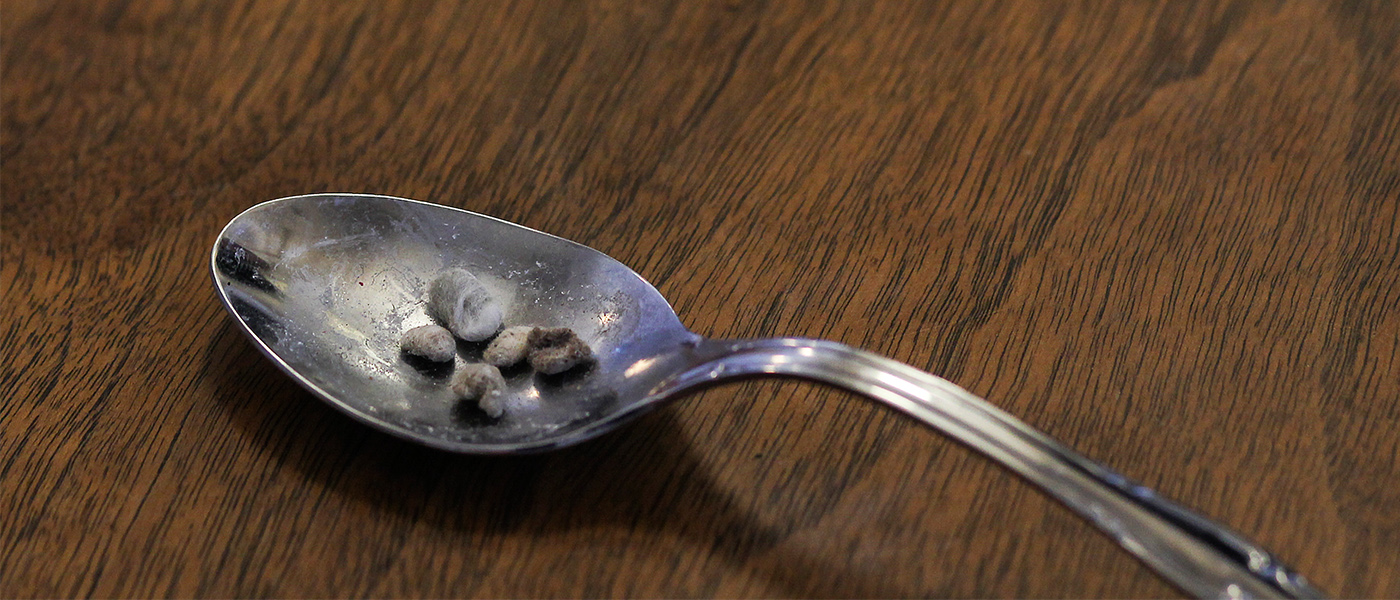

A confiscated heroin cook spoon with bits of balled cotton, displayed for a picture at the police station. (Cheryl Senter/The New York Times)

POPPING PILLS

Police and medical officials warn the heroin problem, as in the case of Stone’s son, might not start with heroin. They say prescription painkillers might feed it. Heroin comes from the opiate family, made from the opium poppy – the same plant used to create prescription medications like morphine, oxycodone and codeine. Young adults and teens use prescription pills at an alarming rate, said Dr. Dorothy Lennon, the medical director at Tully Hill, a chemical dependency treatment center. “The kids get started by using pills they’re getting out of their parents’ cabinets or their neighbors’ homes,” she said. They may start buying the pills to support their habit once other sources run dry. “The kids get hooked on pills, but after a while, the pills don’t do the same thing,” Smith said. “Then they start snorting pills, then they build up tolerance to that. Then they go to heroin, because it’s cheap and if you snort or shoot up some heroin … it does the trick like THAT.” Once lawmakers realized the dangers of painkiller abuse, they restricted when and to whom doctors can prescribe the medications. As the regulations took hold, availability of the pills took a dive, increasing the prices. One pill could cost between $10 and $100. Painkillers are on the decline among young adults 18 to 25, according to the National Survey of Drug Use and Health. Heroin, however, continues to see sharp increases in use.

An $11 million heroin shipment seized en route from New York City to New England. (Provided by the Drug Enforcement Agency)

LETHAL AMOUNTS

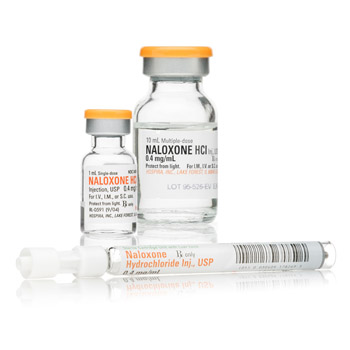

One hit of heroin may be enough for a buzz, but the next hit might prove to be fatal. “It’s like Russian roulette – you never know what you’re going to get,” Smith said. The Sheriff’s Department, along with local emergency medical services providers, are seeing the consequential rise in overdoses in the past four to five years. “We have people who got the same amount, same price, from the same dealer over a period of months, and now suddenly they had a near-fatal overdose because the purity has fluctuated and even the dealer wasn’t aware of it,” said Daniel Taylor, public relations officer and medic at WAVES Ambulance, in Camillus. Taylor says overdoses suppress the respiratory system, causing the drug users to stop breathing. “Very often what we’re seeing is someone who is unconscious, either in respiratory and/or cardiac arrest or very close to one of those,” he said. “When we start treating the patient, they are typically pale, sometimes blue. We may need to start breathing for them immediately. Sometimes their heart has stopped. At that point, we have very limited amount of time to do a number of interventions to reverse a patient’s overdose.” It’s then that emergency medical providers can push Narcan, an opiate antagonist developed in the 1960s. The drug counters the effects of opiates, particularly respiratory suppression and lethal drops in blood pressure. Where they were blue and essentially lifeless minutes before, Narcan can bring them back to a conscious, alert state. “But sometimes they’re violent,” Taylor said. “They may know what happened, and we just ruined a very expensive high for them.” Narcan has been carried by advanced life support ambulances for decades, used regularly via IV by paramedics in suspected opiate overdoses. Recently, fire departments that operate at a BLS level, or basic life support, were allowed to begin carrying Narcan by the region’s EMS protocols. Fire departments routinely go to medical emergencies with EMTs and first responders to help patients immediately and to assist the ambulance on-scene. EMTs are now able to give Narcan through the nasal cavity, or intra-nasally. Solvay Fire Department, a volunteer BLS agency, has begun teaching its members to use Narcan, putting their use of the drug in place in May. “It’s a benign drug,” said firefighter Brendan Hind, the EMS coordinator of the Solvay Fire Department. “In the way that we’re using it, it’s relatively low-risk, except for the reaction of the patient, in case they become very upset or violent.” Previously, the firefighters would be able to breathe for the patient until the ambulance arrived but couldn’t assist in reversing the overdose systemically. “We can be there in two or three minutes after someone’s call for help,” said. “This gives us the ability to administer Narcan safely to counteract the effects. It could be minutes, if not longer, until the ambulance is there, and we can have the patient effectively breathing on their own upon the ambulance’s arrival.” Other local fire departments, including Syracuse firefighters, carry Narcan, as well. The drug is also being given to users and their families. Stone says she and her son both have an emergency Narcan kit. She received her training for the drug in May. “I have to have it,” she said. “I have to have it in case I have to save his life. He could die. He’s putting a needle in his arm, he’s injecting heroin, and he could die.” She says she frequently checks to see if her son is still breathing while sleeping. If he’s not breathing, she says, she’s ready to administer the Narcan. When respiratory or cardiac arrest can be stopped or reversed, users have a good chance of recovery. But Smith says most will continue to use heroin, until the next overdose. “The frustrating thing is it doesn’t just end with a trip to the hospital,” he said. “I don’t think an overdose typically stops anyone, unless it kills them.” Many users who are taken to the hospital by ambulance after an overdose leave the emergency department against medical advice.

Theresa Drumond jabs her arm repeatedly to shoot up heroin, under a bridge in Portland, Maine, June 21, 2013. The proliferation of prescription opiates like Vicodin and OxyContin has altered the landscape of addiction and relapse, with many addicts switching back and forth between pills and heroin whenever one is more available. (Cheryl SenterThe New York Times)

GETTING TREATMENT

More people using has led to a boom in treatment for opioids. “There’s more of a demand for services than there is the availability of services,” said Mark Raymond, the clinical supervisor for the opioid treatment center at Crouse Hospital. “There’s a low percent who just discontinue use and move on with their life.” A few local centers treat heroin addiction, many in different ways. Crouse is the only center in the area to use methadone to treat the addiction. The medication occupies opiate receptors, to block withdrawal and craving sensations. It’s a highly regulated medication, with those who are being treated coming to the clinic every day. Other doctors prescribe suboxone, a drug that works in a different way to treat addiction. There’s a special license to treat patients with suboxone, with specific regulations. Doctors can treat only a limited number of patients under their license each year with the medication. Because of this, and the influx of those needing treatment, doctors are constantly seeking new providers. “We’re always searching to find physicians in the area that have the availability to take on more heroin-addicted patients,” Lennon said. Heroin users are also highly vulnerable to relapse, Raymond said. That’s why treatment – whatever method a user chooses – is so necessary, he said. “When you see someone completely turn their life around through therapy, it’s amazing,” he said.SAVE LIVES, OR ENABLE DRUG ABUSE?

Maine Governor LePage.

Photo from www.maine.gov

![DrugsPills[1]](http://syracusenewtimes.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/06/DrugsPills11-1024x735.jpg)