Two weeks before she was scheduled to fly back to Afghanistan to observe that nation’s presidential elections, Deb Alexander found herself leaping out of a Blackhawk helicopter into the Louisiana night in the company of her newfound friends in an Army brigade. It wasn’t her first jump from an aircraft. That took place over the burning city of Sarajevo in 1999. But Alexander, a 58-year-old former Syracusan, swore it would be her last … a pledge she has made and broken before.

This parachute adventure over a peaceful bayou came as a thank you gift from the brigade commanders for the three weeks she had spent training them in her field: peacekeeping and development. It’s a specialty she has honed in work on three continents in a career that she began with graduate studies in the early 1980s at SU’s Maxwell School of Citizenship and Public Affairs and nurtured in years spent running political campaigns and elections in Onondaga County.

“It was their way of saying, ‘We are so grateful,’ ” recalls Alexander from the quiet of her new home outside Lexington, Ky., a few days after the jump. “I’m thinking a nice bottle of white wine, a little certificate. But once they say, ‘We thought you’d really like to jump out of a helicopter,’ you can’t really say no.”

What was it like?

“It was like being scared to death,” says Alexander.

But she took the gift as a challenge and found herself on a moonlit night strapped to a man she describes as “a very experienced colonel,” descending toward a field thick with wild horses.

“All I could think of was one of us landing on and hurting one of these horses,” says Alexander.

The Syracuse Roots

Her enthusiasm for democracy-building began in Syracuse, where she cut her teeth on the election campaigns of women such as Elaine Lytel, a former Onondaga County Clerk, and Rosemary Pooler, a judge on the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit, and a former Congressional hopeful. Alexander recalls voter registration drives on the South and Near West sides of Syracuse, experiences not all that different from the sense of empowerment she later encountered in places like Serbia and, eventually, remote provinces of Afghanistan.

“It was about expanding the franchise,” she says.

She was also involved in political protests in Syracuse, some of them against the military and State Department she now serves.

“I can remember standing arm-in-arm on East Genesee Street as right-to-life protesters tried to break into Planned Parenthood. That’s when I started paying attention to public policy and got interested in who got elected. I started to care about how our money got allocated,” she says.

Alexander participated in a demonstration at the first SU commencement in the Carrier Dome, in May 1981. Demonstrators who were dressed as bloody nuns and peasants interrupted the commencement address of then Secretary of State Alexander Haig, and their protest against the war in Central America was captured in a front-page photo in The New York Times. She opposed U.S. soldiers training Latin American human rights violators at the School of the Americas, in Georgia, and helped with a local solidarity campaign to market Nicaraguan coffee to Syracusans.

Thirty-four years later, Alexander has worked for three secretaries of state (two of them women) and spends weeks at a time as a Defense Department contractor training U.S. troops. The irony is not lost on her.

“There’s an odd consistency about how I’ve been working through my life,” she says. “Sometimes it’s about protest, and sometimes it’s about working in the biggest institutions in the world: Department of Defense, Department of State. In all those places, I try to find where I can effect change, how can I make my voice heard.”

Starting in the Balkans

It was the signing of the 1995 Dayton peace accords, which ended the Balkans conflict, that pulled Alexander away from Syracuse. She had recently completed her doctorate from the Maxwell School when the phone rang at her home on Kensington Avenue, where she considered herself a full-fledged citizen of the Westcott Nation.

“I got a call from the State Department. They were looking for someone who understood something about elections,” she says.

She ended up in Bosnia and Croatia working with the Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe through much of 1997 and 1998 as those countries held their first elections after the Soviet grip on Yugoslavia loosened. Then it was Croatia and Estonia, Albania, and finally back to Washington in August 2001.

“It was a wonderful time: I would spend four months in Albania, three months in Serbia, wherever the OSCE needed me,” she says.

Then al-Qaida attacked Washington and New York in September 2001.

“My stuff hadn’t even arrived from Belgrade when 9/11 happened,” she says. “Operation Enduring Freedom began in October, and I knew a week later that I was going to Afghanistan.”

When she arrived in Kabul in early 2002, Alexander harbored no illusions that the war would be quick.

“If you asked on Sept. 12 what it would take to build a new Afghanistan, we knew it was going to be a bigger mission that what we talked about, but we didn’t want to scare off the public with talk of the costs in the billions,” she says. “Our objectives were to dismantle al-Qaida, but even in those early days it was about supporting self-government and reconstruction. Once you go down that road and talk about stability and reconstruction, you’re not just talking military operations, you’re talking about political change and institution building. I don’t think there was a full appreciation of the money or the effort that would take.”

No one keeps statistics on things like this, but it is quite likely that Alexander has spent more time in the Afghan theater than any other U.S. civilian. Over the course of nine years, she held positions with the U.S. Agency for International Development and the State Department. Her focus was on building local democratic institutions in the midst of a war, battling the Taliban on the one side and the notoriously short attention span of the U.S. public on the other. That eventually led her to work as a contractor training the Army brigade in Louisiana.

Violence Thwarts Return

Just days after the night-time skydive, the Taliban crushed her plans to return to Kabul when they attacked the headquarters of the Afghan Election Commission for the second time in a week. Alexander spent many days in that building during nearly nine years in Afghanistan. Until the attack on March 29, she was determined to be in Afghanistan for the voting, in spite of an earlier assault on election observers at the Serena Hotel, a Kabul expat hangout she knew well. One of the dead in that attack — Luis Maria Duarte, of Paraguay — had been a colleague and roommate during an earlier election monitoring effort. A few days after the Serena attack, six Afghan police officers were killed by suicide bombers as campaigning leading to the voting on April 5 wound down.

She wanted badly to be in country while Afghans chose from among eight candidates to succeed Hamid Karzai, the term-limited president who has held office since 2001. A runoff between the two candidates who receive the most votes is scheduled for May 28. If all goes well, as she thinks it will, later this year Afghans will see a peaceful presidential transition.

That would be a first, and if it happens, Deb Alexander could be forgiven for taking a share of the credit for making history. But she won’t. In her soft Kentucky drawl, she regularly lapses into telling stories of those Afghans and internationalists who worked by her side and didn’t live to see this moment.

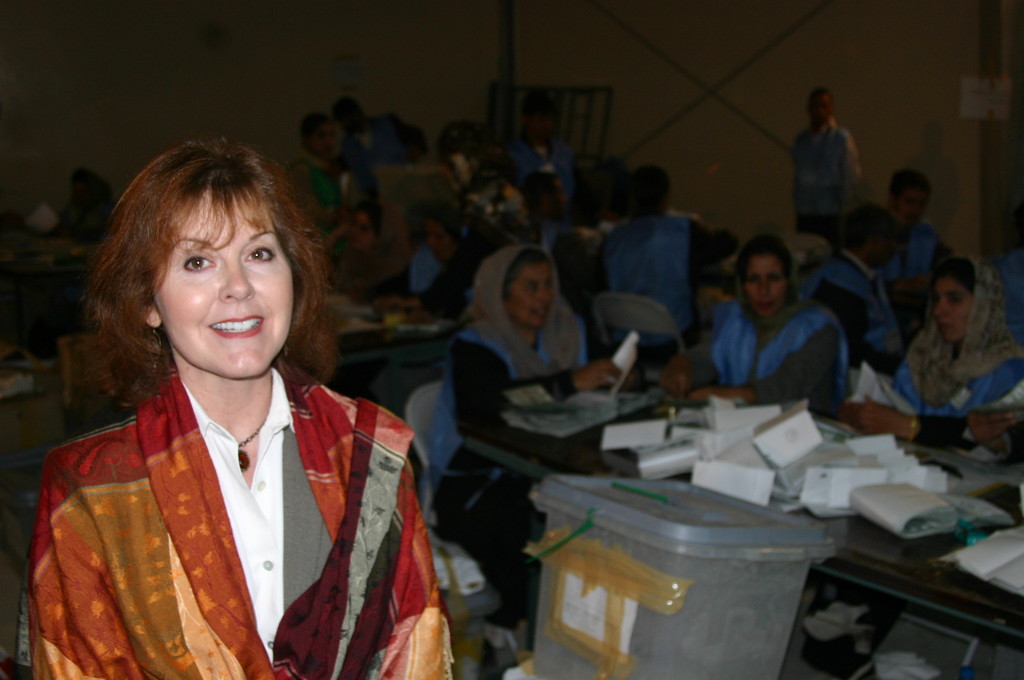

“I’ve been there for all four elections, the presidential elections in 2004, the parliamentary and provincial in 2005, the 2009 presidential elections, and 2009 provincial and parliamentary. In 2004 and 2005, I trained and organized the first Afghan observer group. That was one of the proudest things I ever did. These were young people who never saw an election before. I was the lead person for the U.S. embassy for elections, coordinating aid for the elections commission.”

Even after her election monitoring trip was canceled, she sounded hopeful about Afghanistan’s future.

“Contrary to some myths,” she says, “Afghans do understand democracy and electing their own representatives and their own president. This will be their fifth election. There will be complaints. There will be recounts. The average Afghan will have voted and the next day will go to work. My hope is that they will have a new president in six months, and Afghanistan won’t fall apart. They will have passed the test.”

While some view reports of car bombs and terrorists with weariness or indifference, Alexander scours press stories for the names and faces of people, she knows. Her memories of those years including meeting secretaries of state, British prime ministers, Prince Charles of Great Britain, generals and commanders of various rank, but she remains most impressed by the Afghan women who were the focus of her work.

“Most of my time was spent out in the provinces, in the villages and the towns. I made a point of people understanding that I was a political officer or development specialist.”

Serving as a civilian officer working for the U.S. government while the U.S. military occupied Afghanistan was sometimes a hard line to walk. While she did her best not to be mistaken for someone working in covert operations, “you say to someone that you work for DOD or DOS or AID, and it all sounds very similar, like CIA. I’m not sure the average Afghan cared who was paying my paycheck.”

Alexander survived three roadside bombings without serious injury. She’s lost count of the number of times she has exited or entered a building under fire. She has escaped physical harm and has been spared the trauma of serious post-traumatic stress disorder, suffering only from some disorientation as she adjusts to U.S. consumer culture.

“The worst part is the guilt,” she says. “I ask, ‘Why them and not me?’ How did I survive rocketings, three attacks? There is no rhyme or reason it seems, as to who lives or dies in war.”

The Three Musketeers

Though she sounds remarkably upbeat, it is clear that the years there have taken their toll. By her count, 32 friends and colleagues have been killed in the war and terrorist campaign, including one whose body parts she helped recover from the front gate of a building after a suicide bombing.

“One of the downsides to the work that I’ve done is that, sadly, you become desensitized to the loss of people that you love. That’s one of the reasons that I wanted to come home, so I could pinch myself and feel the pain of the loss.”

In autumn 2008, Alexander worked with Paula Loyd, a former U.S. Army sergeant, as part of the Kandahar provincial reconstruction team. Loyd had finished her tour of active duty with the Army and had returned to Afghanistan as an anthropologist, working at times with the U.S. Agency for International Development alongside Alexander.

In 2008, Loyd was working as an anthropologist with BAE Systems PLC, a multinational corporation based in Great Britain, as part of what the army referred to as a human terrain team (HRT). Anthropologists like Loyd were embedded with the troops to help them understand the cultural, religious and other human aspects of the society in which they were fighting.

Working in Kandahar brought Loyd and Alexander into contact with an Afghan woman police officer, Malalia Kakar. Kakar, the daughter and sister of police officers, was in her second stint serving with the Afghan police. Her earlier police career was cut short when the Taliban came to power and forced women like her to stop working outside the home. Now Kakar, the mother of six, was eager to reclaim the right of Afghan women to participate in law enforcement. She was exactly the type of strong woman that Alexander sought to support.

The threesome became tight. They referred to themselves as the Three Musketeers.

“We spent most of our time out meeting as many Afghans as possible, particularly women,” Alexander says. “We were an awesome threesome: Afghan and American, civilian and military, police assistance.”

One day in September 2008, Kakar was gunned down while walking to her car to be driven to work. The assailants, presumably Taliban, sped away on motorcycles.

Two months later, Loyd was doused with gasoline by a suspected Taliban, who then set her on fire. Loyd was airlifted stateside for treatment but died in January 2009.

“Paula had an enormous heart and great talent,” says Alexander. “Everyone who knew her — men and women, children — were drawn to her gentleness and kindness.”

Loyd’s assailant, Abdul Salam, was captured on the spot and cuffed. A military contractor assigned to guard Loyd, Don Ayala, executed Salam with a single gunshot to the head. Ayala was later sentenced to five years’ probation by a federal district court judge in New Orleans and fined $12,500.

Loyd’s gruesome death, the execution of Abdul Salam and the judge’s leniency toward Ayala offer a glimpse into the cycle of violence that makes outsiders feel hopeless about U.S. efforts in Afghanistan. But Alexander, the sole surviving musketeer, doesn’t give up hope.

“The idea that you can’t help bring democracy to Afghanistan,” she says bluntly, “that’s a bunch of crap.”

The Question

People often ask her if it was worth it.

“After 9/11, the question was, ‘Did we dismantle al-Qaida and displace the Taliban, did we get bin Laden?’ Yes. I think about Paula Loyd, the lives lost, the billions invested. Was it worth it? I don’t have the answer to that. Maybe I can speak to that in 25 years, if I’m still alive.”

But when she looks at a picture of a group of Afghan children in a village where she once worked, she asks, “How can you not care about their future?”

She laughs when she talks about being scared — “Walking late at night in D.C. is more dangerous than Afghanistan, most of the time,” she insists — then turns around and heads right back into places most of us associate with danger.

Alexander plans to travel to Ukraine in mid-May as a human rights monitor for the Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe “to keep an eye on what Russian troops are doing on the eastern border.” Military observers by OSCE have since been taken hostage in Ukraine, putting that trip in jeopardy. She has her bags packed and is waiting for updates.

If the Ukraine trip falls through, she might slip in a visit to Syracuse friends, then return to Kentucky to care for her Mother and Hooch, a cat she smuggled home from Kabul.

With a hint of wistfulness, she adds, “Eventually, I will come back and put in a garden.”

For more on Paula Loyd, CLICK HERE

For more New Times cover stories like ‘The Last Musketeer’ – CLICK HERE