Emerging as a new technology in the 1980s, three-dimensional printing has come a long way from its humble beginnings. The process and equipment involved is ever expanding, and what was not possible just a few years ago is achievable today.

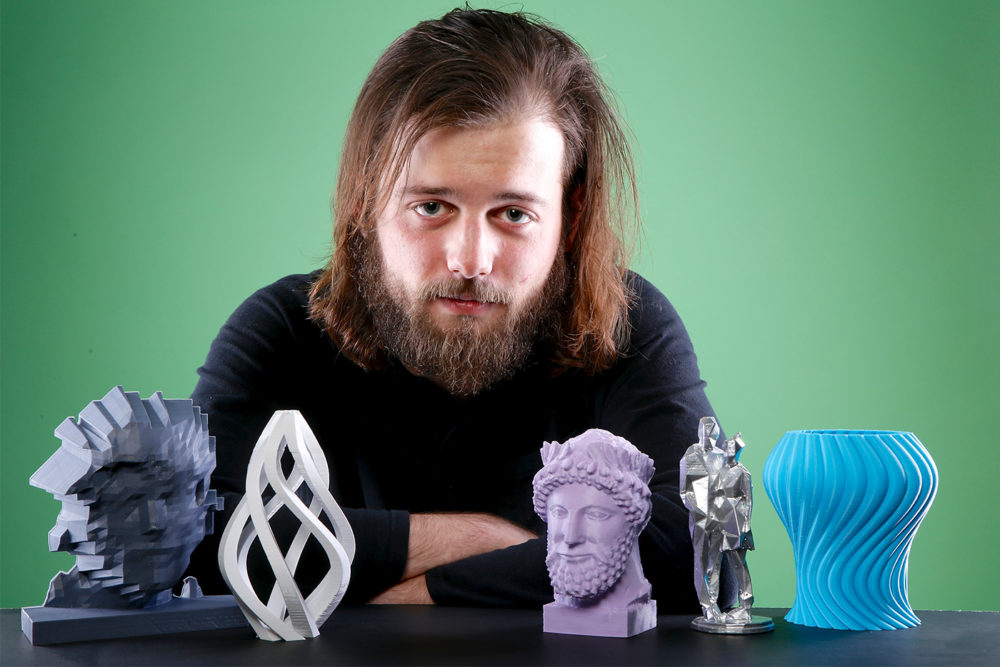

Isaac Budmen is a 3-D freelance designer who is experiencing this evolution firsthand. Budmen, a graduate of Syracuse University, along with SU professor of digital culture Anthony Rotolo, wrote and published The Book on 3D Printing in August 2013.

The two met when Budmen took an SU class taught by Rotolo that was based on the TV and film series Star Trek. Rotolo said that references to 3-D printing in his lectures caught the attention of Budmen. What materialized after that was the beginning of a strong working relationship.

“He was there at the front of the room, asking me more about it, wanting to study it, wanting to learn about it,” Rotolo recalled. “I was certainly aware of 3-D printing but was by no means a practitioner of it. So Isaac, overnight, sort of became that, and I went along for the ride with him because it was fascinating. (This is) what ultimately culminated in the book.”

Budmen said that at the time the book was written, there were no adequate resources to help non-engineers understand 3-D printing. When he finally got his hands on a 3-D printer, he investigated Internet forums to help guide him while learning to operate his new machine.

“We walk folks through this in a way that engineers will understand but that is friendlier for people like teachers and someone who isn’t technical,” Budmen said. “If I were an engineer, I’d pick this book up so I could talk to my friends without sounding like a nerd.”

The basic process of 3-D printing is similar to a hot glue gun. The material the objects are made of is a plastic that starts out as a 2-D object. The 2-D layers are then stacked to eventually create a 3-D object.

Before getting started on printing, however, a model must be constructed using designated software, which can range in price and quality. After learning how to operate the software and the printers, the possibilities are nearly endless for what can come to life.

“It got to the point where I had been doing so much of this stuff, Anthony and I looked at each other and he said to me, ‘I think you might know more about this than most people on the planet,’” Budmen said. “So we did a bunch of research on what’s out there right now. (There wasn’t) much. Everything that was an easy-to-read guide to 3-D printing wasn’t substantial enough. So that’s where we kind of saw this opening.”

Budmen and Rotolo gathered all they had learned while experimenting in 3-D printing and compiled what they determined were the most important elements. Rotolo uses the book in his classes at SU so students with minimal experience with the technology can easily grasp it.

“One of the things that initially attracted me to work with Isaac was that he has this really expansive vision,” Rotolo said. “(He’s) often not looking at ‘What does it do right now?’ but is asking the question, ‘What else can it do?’”

After creating the “how-to” 3-D printing book, Budmen’s work crossed over into other projects, which includes the art of 3-D scanning. In 2014, he successfully scanned the Holden Observatory at SU, with the help of friend Arland Whitfield, by using a camera attached to a drone.

The drone soared around the building as the camera captured many photos taken at different angles. Budmen said the software was then able to construct a rendering of the building using the compiled images.

“What the software does is it reconstructs from the photo texture to the actual texture of the building,” Budmen said. “This is, as far as we know, the first building that was ever 3-D scanned with the sole intent of 3-D printing.”

Budmen said there is a difference between having what he called a “drone-o-graph” of the building and simply modeling it to the best of one’s ability. The scanned object captures the age of the building and the renovations it has gone through. He also said the idea of scanning historical monuments every 100 years could be beneficial information that should be archived.

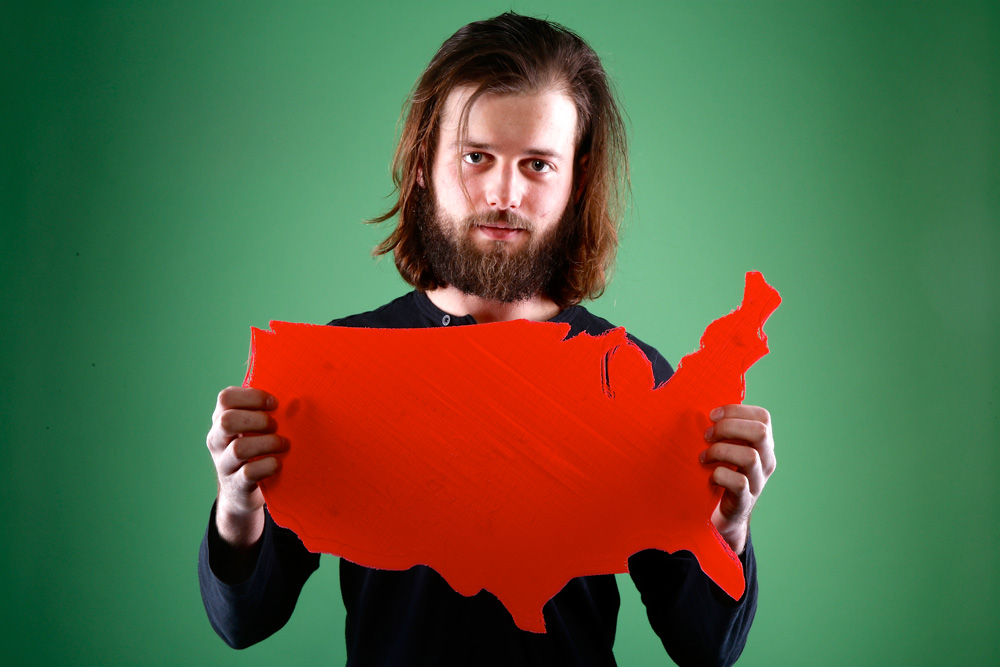

Budmen is intrigued by the concept that scans could be uploaded to the Internet for educational purposes, such as the one he did on the Holden Observatory, which can be viewed at Budmen’s website, teambudmen.com. Anyone with access to a 3-D printer could print his scan, which is where the idea of scanning and printing monuments originated.

“There’s real value in being able to personalize and capture the things around us in three-dimensional form rather than just as a photo,” Budmen said. “A photo only tells us so much information.”

Budmen had a chance to further experiment with this procedure during his time at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City. He also tested other methods used to preserve and even expand on famous pieces of artwork.

“When you are able to take something that already exists in the world, and feed that through the technology, it gives us new ways of understanding it,” Budmen said. “What they told me to do was go walk around and create stuff in response to the collection. So that’s what I ended up doing.”

During his time at the Manhattan museum, Budmen scanned many pieces of art, then used these scans to manipulate the pieces in several ways. This included adding specific finishes to scans once they were 3-D printed, such as a metal appearance to give the illusion of texture using sands and dry brushes.

Budmen was also able to take 2-D paintings and add depth to them using the technology that 3-D printing offers. It’s a process that he calls dimensionalization.

“I took a Picasso painting that had this really amorphous, kind of biological-looking sculpture,” Budmen said. “(Picasso) had originally hoped for this to be like a monumental sculpture, but no one would commission him to make it, so he had to paint it.”

Budmen was able to make Picasso’s original intentions a reality, as well as with other pieces. This included aspects of paintings by other artists such as Vincent van Gogh.

Michael Davis photo | Syracuse New Times

Prior to his work at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, Budmen first experimented with dimensionalization with local artist Adam Lister. Lister’s method involves using already existing artwork and photographs to create 8-bit versions of them.

“He wrote to me and proposed sort of a trade,” Lister said. “I was going to make a painting in my kind of geometric technique, and in exchange, he was going to design a 3-D print based off of one of my paintings.”

Budmen and Lister’s eventual series of paintings and 3-D prints, titled “8 Bits, 3 Dimensions,” is available to view at 8bits3dimensions.com. “It was a good collaboration,” Lister said. “The images I created, according to him, really lent themselves to 3-D printing.”

Aside from his work with 3-D scanning and dimensionalization, one of Budmen’s goals is to make 3-D printed furniture to sell on the Internet. He hopes to have a website where people can customize the furniture to their liking, including size, color and other characteristics.

“People will be able to take a set of sliders (on the website) and decide how tall they want (the chair). How wide do they want it? How many facets do they want?” Budmen said. “They’ll be able to design a piece of furniture. The reality is, I’ve designed it ahead of time. All they’re doing is tweaking it.”

Budmen noted that 3-D printing is still far from where it could be. The limitations have to do with the plastics and other materials being used.

“The robots we have inside the printers can run a lot faster than we’re running them right now. That technology is pretty good,” Budmen said. “We’re only utilizing about 40 percent of the actual robot’s capability, and that’s largely because the materials haven’t caught up yet.”

Yet Budmen has dedicated his life to inventing. Since involving himself with 3-D printing, he believes the art form will play a large role in the future in terms of our perception of reality.

“What I love about 3-D printing is that it has this incredible ability to materialize our imagination,” Budmen said. “This is a way that you can take things from your imagination and you can literally hold them in our hand and make them a part of the real world.”

Discovery Zone at SALT Makerspace

For those interested in doing some inventing of their own, the SALT Makerspace, 201 E. Jefferson St., provides a community hub for creators of all kinds. The Makerspace not only offers a spot for local inventors to experiment and produce, it also features classes to assist in the creative process.

Director Michael Giannattasio explained that the printers in the SALT 3-D printing workshop area, along with 3-D printers in general, contain their own software that is designed to handle STL (Stereo Lithography) files.

“(An STL file) is an exported file format that these machines can actually understand and translate into three-dimensional form.” Giannattasio said. “(These STL files can be made) using SolidWorks, which is a program we have here, Rhyno, Tinkered or Google SketchUp.”

The software used to generate 3-D objects isn’t for everyone. Luckily, Giannattassio’s workspace is open to anyone who wishes to learn the craft. The Makerspace comes with all the materials anyone would need to create their vision at an affordable price.

“We have about five different 3-D printing style workshops,” Giannattassio said. “So (anyone) could come in without any skills and get an introduction to the software. Once they have that introduction, they can go home and, utilizing some of the free softwares and designing, they could send us the file and we could 3-D print them.”

Memberships are offered for anyone wishing to take advantage of the materials, giving individuals access to the space and work as they please without any guidance. This includes designing on the computers provided, as well as working with the printers. For information on memberships, visit saltmaker.org.