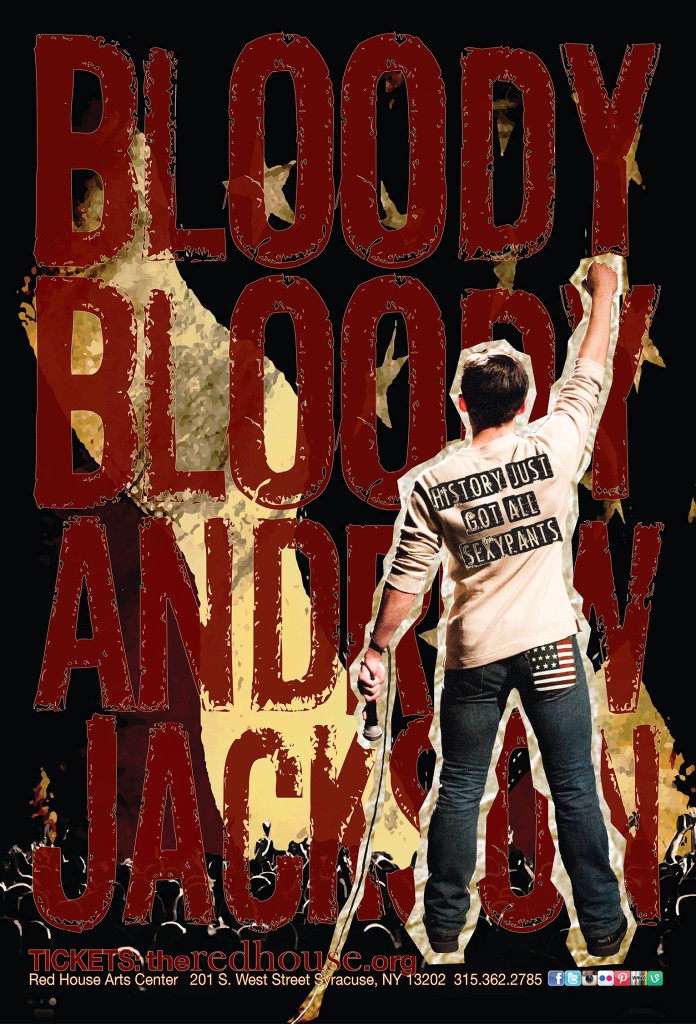

When the emo rock opera Bloody, Bloody Andrew Jackson by Alex Timbers (book) and Michael Friedman (music and lyrics) opened off-Broadway at the Public Theater in spring 2010, it quickly became the hottest ticket in town. But when producers fecklessly moved it to a huge Broadway house later that year, the excess oxygen and elbow roomed dissipated all its manic energy. That’s why that tight space at the Redhouse Arts Center makes it the perfect venue for this blast from the past. And director Stephen Svoboda, the man who embraced the circus in Stephen Sondheim’s Assassins and the demonic in Batboy: The Musical, is the right guy for the Syracuse premiere.

Bloody is, among other things, also a demonic circus. Most students know that while the first six presidents of the United States, from South and North, were all refined, well-educated gentlemen, Andrew Jackson was a rude frontiersman. At his inauguration his supporters rioted and trashed the White House.

In the first production number, “Populism, Yea, Yea!,” the whole company raises its fists to the audience. Jackson, his family and his followers bear many hatreds: the English, Spanish, French and Indians but most of all they loathe privilege. Early in the action when Andrew Jackson Sr. (Eric Feldstein) hears mention of the grand homes in the Northeast he breaks into a string of epithets.

Other epithets come in streams, gobs and floods. We hear the F-bomb perhaps 80 times. It is the verb of choice when yearning women say they would like to be intimate with rock star Jackson. Artistically, Timbers and Friedman’s use of rough language is far more justified than, say, what David Mamet does in Glengarry Glen Ross. Not only is this a rock opera, what Tom Robinson called “nasty, crude, rebellious people’s music,” but the show is portraying a dynamic and deeply divisive figure.

Given that this show also engages in scabrous satire, like portraying John Quincy Adams as a whining infant, it is moving into territory first charted by Bertolt Brecht and Kurt Weill. This Andrew Jackson bears more than a passing resemblance to Mack the Knife. He’s not cuddly, and we’re not supposed to love him.

The historical Andrew Jackson, the guy on the $20 bill, is one of our greatest presidents, and the Jackson of Bloody is a great role. Brian Detlefs’ portrayal brings some of the swagger and mystery of Jim Morrison along with the sexual dynamism of the young Elvis Presley, minus the vulnerability. He matures and changes before us. After being imprisoned by the British, he disdains taking a role in public life in “I’m Not That Guy.” Shortly after he insults a haughty George Washington and suffers depredations from the Spanish, which stiffens his resolve. When the U.S government appears unconcerned with his plight, he declares, “I’m So That Guy.”

All along anachronisms run riot. The well-born wear white wigs (gone many decades by Jackson’s time) as well as Elizabethan neck ruffs. British soldiers at the Battle of New Orleans sport Union Jack tabards and go into battle sipping tea with one pinky raised. Female staffers wear cheerleader outfits, and the White House’s red telephone is good for ordering pizza. This is not nonsense. Timbers and Friedman are asking us to recognize that rough populism is still with us. In Jackson’s day it thrived on the left, but after Nixon and Reagan’s Southern strategy it migrated to the right.

The historical Jackson was a slave holder and defender of slavery, an issue that never arises in Bloody. The show already covers huge territory in the space of an hour and 45 minutes without intermission. He dispatches enemies, especially Indians, without reflection, but his great moral challenge is the vicious uprooting of whole tribes and the betrayal of a loyal ally, Black Fox (Jacob Sharf). For this unexpiated sin he hears the charge, “American Hitler.”

This is a rock opera, what Tom Robinson called ‘nasty, crude, rebellious people’s music.’

We should not forget that Bloody, Bloody Andrew Jackson is a rock opera and raucous good fun. Patrick Burns, who also contributes wry narration, leads a five-player ensemble seen high above the 18-player company. A few numbers are effective when disarmingly subdued, as in Marguerite Mitchell’s ironic and Brechtian recitation “Ten Little Indians,” about the dismissal of native peoples. Choreographer Angela Colabufo has her best big production number right in the middle of the show. “The Corrupt Bargain,” another slice of Brechtian irony, demonstrates how the privileged—John C.

Calhoun (Eric Feldstein), James Monroe (Jacob Sharf), Henry Clay (Tyler Spicer), along with Jackson’s pal Martin Van Buren (Chris Baron)— describe Jackson winning the popular vote but losing the election through manipulation of the electoral college to the pampered son of a former president, John Quincy Adams (Benjamin Wells). Insinuations about George W. Bush in the 2000 election are fully intended.

In Bloody, Bloody Andrew Jackson Sam Cooke is superseded. Not only do we know much about history, but it’s still with us. o

This production runs through Oct. 19.