In living rooms across America, it has been hard to turn on the television in the last two months without seeing a political advertisement. Candidates are shown on the campaign trail or in their kitchens with their families, talking in soothing tones about how they’ll do great things. Ever since televisions entered American homes in the 1950s, television advertising has been a major part of political campaigning.

“Advertising – any sort of advertising – is a mixture of art and science,” said Brian Sheehan, an associate professor of advertising at Syracuse University and author of Loveworks: How the World’s Best Marketers Make Emotional Connections to Win in the Marketplace (2013).

“At the end of the day, political advertising is advertising,” Sheehan said. “Instead of selling a product, you’re selling a person or that person’s position.”

The most common distinction between political ads and other ads is the stark contrast between positive and negative strategies. Sheehan says that few ads attack their competition in the way that political ads do.

“Most people out there are talking about why their product is great,” he said. “Political advertising is defined largely by how much of it is negative.”

Bill O’Reilly, a strategist for New York Republican Rob Astorino’s gubernatorial campaign, has been designing political ads for more than 30 years.

“In a focus group, you can run a very positive ad of someone and everyone in the room will say, ‘I love that spot, I really felt a connection,'” O’Reilly said. “And then you run the negative spots and they’ll say, ‘I hate those ads, I can’t stand when politicians do that.'”

But when researchers ask participants later what they remember, they often remember the ads they hated.

“People carry away negative information,” O’Reilly said. “Somehow we’re hardwired for that.”

Bob Thompson, a professor and director of the Bleier Center for Television and Popular Culture at Syracuse University, says that the artistry of political ads is judged differently than other forms of art.

“Generally, in the case of film or television, it’s ‘how beautifully is it shot?’ ‘How well done are the compositions?'” Thompson said. “Sometimes that’s the last thing you want in an advertisement.”

Instead, the goal of political ads is often simply to “convince people that the other guy is a crook and that you aren’t.” Candidates may also cheapen the quality of their ads to avoid criticism for spending too much money.

The correct balance of inspiration and fiscal conservatism, Thompson says, is an art form in and of itself.

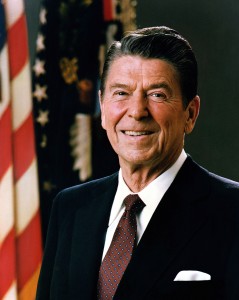

When asked about iconic political ads, historians and advertising experts often point to an ad aired by the Ronald Reagan re-election campaign in 1984. Many felt that Reagan had filled a leadership gap and raised the spirits of Americans frustrated by the Iran hostage crisis and the economic downturn. The 60-second “Morning in America” ad featured images of Americans going to work, getting married, and raising the American flag.

“Whether you liked Reagan or not, [the ad was asking], ‘Are we better off than we were four years ago?'” Sheehan said. “The resounding answer was ‘yes.'”

Negative ads have been around as long or longer than their positive, more cinematic counterparts.

“If you look at the early American period, the elections between the Federalists and the Democratic Republicans were fierce,” Sheehan said. “They would tear each other apart personally.”

The first campaigns to include television commercials were the 1952 and 1956 presidential campaigns, both between Dwight Eisenhower and Adlai Stevenson. In one of the first attack ads ever run, “Nervous About Nixon” (1956), Stevenson implied that Eisenhower was old, and the presidency may soon be in the hands of Richard Nixon, who was not well-liked.

Soon after, in 1964, incumbent President Lyndon B. Johnson ran what is considered one of the most iconic ads of all time: the “Daisy” ad.

A young girl stands in a field, plucking petals off of a flower and counting to ten. She miscounts, and a man’s voice takes over, counting down as if to the launch of a missile. The image of a nuclear explosion overtakes the girl, and the voiceover proclaims, “These are the stakes. To make a world in which all of God’s children can live, or to go into the dark. We must either love each other, or we must die.”

The ad aired only once on NBC. Sheehan says its message and imagery played on Americans’ deepest fears.

“We thought any given day, we were going to be blown off the face of the earth by Russians [sic],” he said. “This little girl – she represented innocence – was going to be blown to smithereens, and the question was: ‘Who do you want on that trigger?'”

The ad, which celebrated its 50th anniversary this September, was copied by O’Reilly and the Astorino campaign in New York. They followed a similar formula: a young girl counting flower petals, an explosion, and an ominous warning – this time, against re-electing Governor Andrew Cuomo, “who may end up in jail.” O’Reilly says the goal was to reintroduce the Moreland Commission corruption investigation, which is still underway.

O’Reilly has not been the only strategist to rehash an old ad. Hillary Clinton’s 2008 “Red Phone” ad, which asked, “Who do you want answering the phone?” was similar to one run in 1984 primary by the Walter Mondale campaign against Gary Hart. Reagan’s “Bear” ad, which equated a bear with the Soviets, was the inspiration for George W. Bush’s 2004 “Wolves” ad, which equated a pack of wolves with terrorists. “Bill Clinton’s 1993 “We Can Do It” message of hope and change was echoed in 2008, with “Yes We Can.”

But copying a successful campaign ad is no guarantee of a successful bid. And Sheehan says that when strategists say that they knew an ad would be a hit, they’re lying. A great ad is almost impossible to predict.

“Good ads touch a nerve,” he said. “Great ads touch the right nerve at exactly the right time – for everybody. These are once in a generation ads.”

Five iconic and artistic political ads

1. “I Like Ike” (1952) – This ad aired in the 1964 presidential race between Dwight Eisenhower and Adlai Stevenson, and featured a short animation by Walt Disney Studios set to a catchy tune by Irving Berlin. Eisenhower beat Stevenson 55.1% to 44.4%.

2. “Daisy” (1964) – Also known as “Peace, Little Girl,” this ad tapped into Americans’ fears of the Cold War. The black and white ad was misleading – the flower was not a daisy, but a black-eyed susan. Eisenhower beat Goldwater 61.1% to 38.5%.

3. “Bear” (1984) – Incumbent Ronald Reagan presented himself as the candidate who would be prepared for the (seemingly inevitable) possibility of nuclear war with the Soviet Union. In this ad, a bear (symbolizing the Soviets) approached a man and, realizing the man’s presence, took a step back.

4. “Morning in America” (1984) – This is perhaps the most exemplary of ads that “hit the right nerve at exactly the right time.” Reagan beat Walter Mondale 58.8% to 40.6%.

5. “Yes We Can” (2008) – This ad – or rather, music video – was not produced by Barack Obama’s campaign, but was influential in the 2008 election nonetheless. The song was written by Black-Eyed Peas frontman will.i.am, based on a speech given by Barack Obama. It featured familiar faces of artists like John Legend, Herbie Hancock, Scarlett Johansson, Common and Tracie Ellis Ross. It became so popular, will.i.am and John Legend performed the song at the 2008 Democratic National Convention in Denver. Obama beat John McCain 52.9% to 45.7%.

Source (and for more great historical political ads): The Living Room Candidate, http://www.livingroomcandidate.org.

Feature Image: Ramiro Piedrabuena. Thinkstock.

Sarah Hope is a graduate student at Syracuse University, where she focuses on television, entertainment history and classical music. Find her on Twitter @sarahmusing.