A Long Journey

Michelle Frankfurter has spent much of her life advocating for Central Americans and recording their lives on film. Reporter Renée K. Gadoua spoke with her recently as attention sharpened on immigration issues sharpened and Frankfurter’s new book, Destino, neared publication

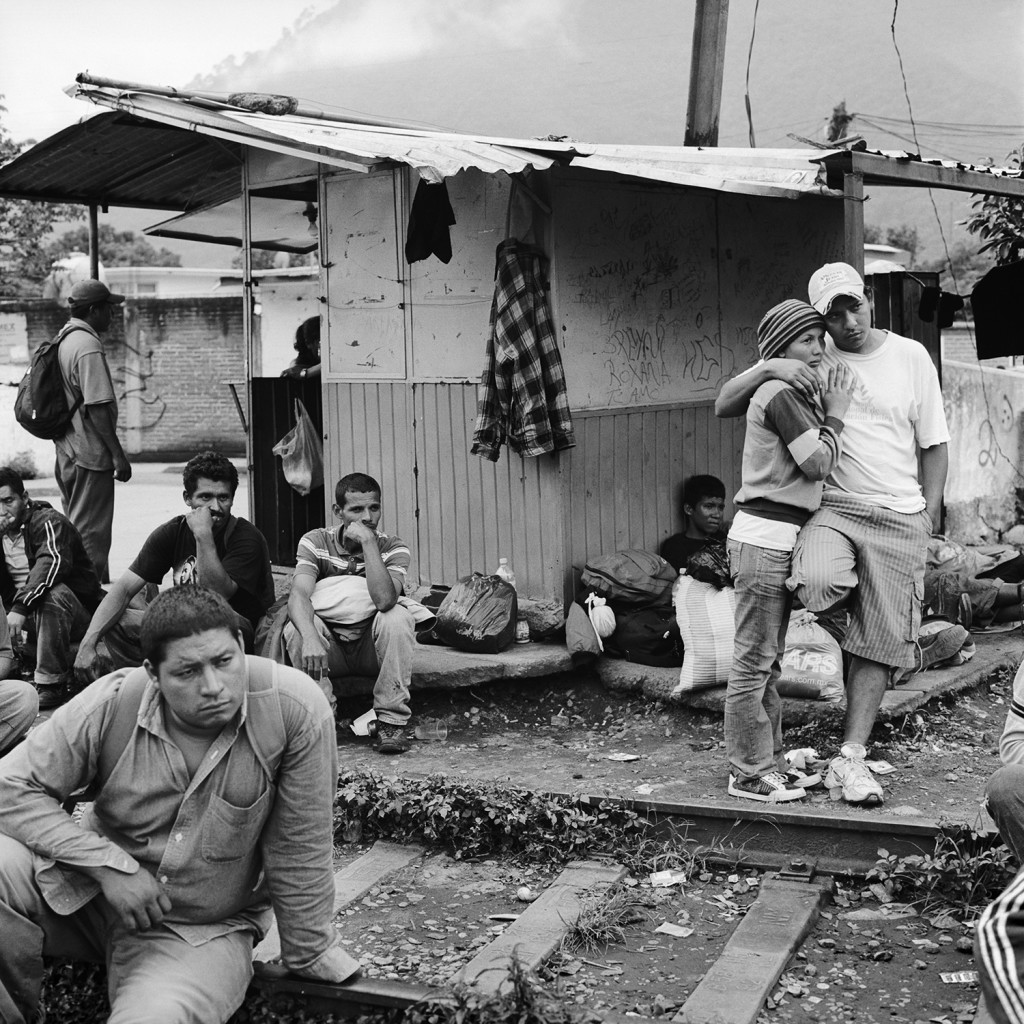

Former Syracuse photographer Michelle Frankfurter started taking pictures of undocumented Central American migrants traveling through Mexico in an attempt to reach the United Sates in 2000.

That was long before U.S. media outlets were paying attention to the increase in unaccompanied minors arriving in the U.S. It was long before Syracuse Mayor Stephanie Minor told federal officials Syracuse would welcome those refugees, spurring a local, polarized debate about immigration policies.

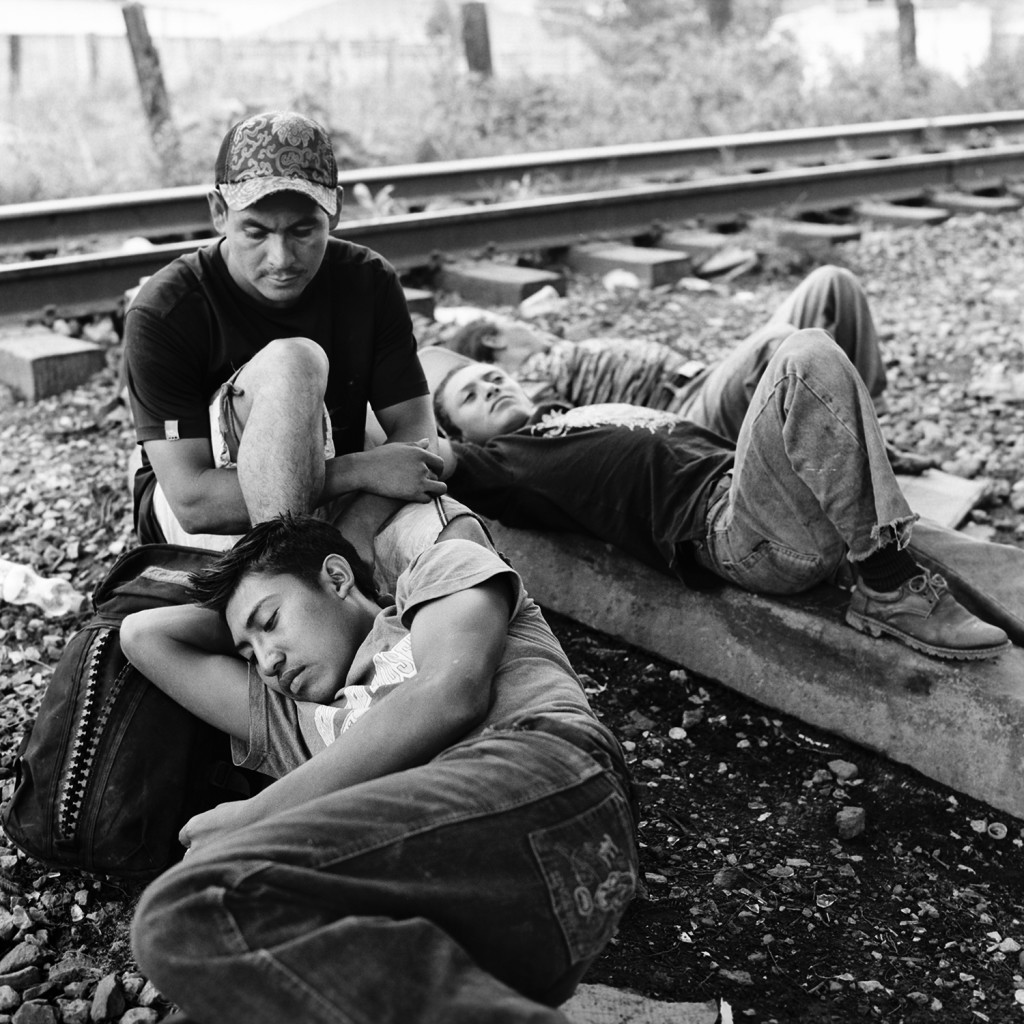

As the national debate about the rising number of unaccompanied minors heated up, Frankfurter was completing Destino, a book of black-and-white photos of migrants headed to the U.S. A successful Kickstarter campaign in the spring raised money for the book production, and the book is out this week.

Frankfurter, a graduate of Jamesville-DeWitt High School and Syracuse University, describes Destino (the word means “destination” or “destiny” in Spanish) as “both a social commentary on one of the biggest global issues of our times and an epic adventure tale.” She talked recently with the Syracuse New Times about her book and the national conversation about immigration.

You are reading the Mobile Version. For the enhanced version (Desktop Users) CLICK HERE

June 2009

What first drew you to this topic?

When I left Syracuse, I went to Guatemala and studied Spanish, then lived and worked in Nicaragua for Reuters and did human rights work. I’ve spent the last 25 years traveling to that region. I’ve been photographing the Texas-Mexican border for years. In 2009, I read Sonia Nazario’s Enrique’s Journey. She’s been very outspoken about undocumented Central American kids whose mothers had left them when they were very young to look for work in the United States. There was a confluence of my interest and the connection I felt with the people of Central America. It manifested itself in this epic journey, an odyssey story. That’s what really drew me.

Why do you think it took so long for the mainstream media and the American government to focus on the issue of unaccompanied minors?

There have been a lot of people looking at this and paying attention and agitating for it. What is frustrating to me is there seems to be a certain segment of our society that constantly is reacting to symptoms that are right in front of them instead of ever wanting to address the root causes. They routinely react with hostility and see no connection to policies that created this situation.

July 2010

What do you make of the polarized politics over this?

It’s a willful determination to not understand the big picture. Trace the history of Central America and look at what created the situation in the first place. In Nicaragua, I documented the recovery of a 12-year-old boy who stepped on a landmine in a rural community. America left these anti-personnel mines where people would step on these and be injured and disabled. The intention of these mines was so insidious. Finally, he went home to his community in very rural Nicaragua where they lived in a shack. There was an exhibit at Lightwork. I remember the letters to the editor: “They’re all communists.” That doesn’t help the discussion or help find a meaningful resolution to this immediate crisis, which is a humanitarian crisis.

How dangerous was this project as a woman traveling alone?

At first, I was really scared. Pretty soon I started feeling comfortable. There was a point when I made peace with it. I thought, “I’m at an age I’ve done what I wanted to do. I don’t think this is about bravado and adrenaline. It just feels important. I understand that things happen, and I’m willing to take the risk.” At the beginning, I said, “I’m not going to get on the train when it’s moving.” Then I said, “I’m not going to get on the train when it’s dark. I’m not going to get on the train when it’s raining.” The third time I did it, all those rules went out the door.

January 2014

You told Smithsonian you felt a responsibility to tell these people’s stories. Why?

Initially, when I went to Mexico, I didn’t have any intention of getting on the train. I thought I would make portraits and go to migrant camps. Then I started talking to them and hearing their stories and why they were leaving. They were so open with me. I felt I couldn’t not do it. I wanted to be the person to tell their stories.

How do you balance your empathy yet keep your professional distance?

I got rid of that line a long time ago. I don’t pretend to be looking at it objectively. I feel very subjective. I’m very much looking to craft a narrative where I’m seeing a story with some characters who are underdog protagonists.

How did your project evolve over time?

That journey by rail has been going on for 20-something years. What has changed is the Mexican cartels that used to be a handful have mutated to 14 or 15. That is a direct result of the cartels taking over the drug smuggling from Colombians, and the war that we have declared on the drug cartels. Since I started taking photos, it became more and more dangerous, with more and more of that train route controlled by cartels.

What kind of danger did you witness?

A couple times, everybody suddenly got really nervous because it looked like something ahead. I did witness the aftermath of people who had been injured. They had fallen and lost limbs. … I completely felt they were looking out for me. In the migrant camps I would stay there and get to know people and they would get to know me. You’re in an extreme situation, so that cuts through layers and layers of superficial chit chat, and you bond with people very quickly. I feel like they were looking out for me, and they were sharing whatever they had with me. I wanted to reciprocate and share with them.

July 2010

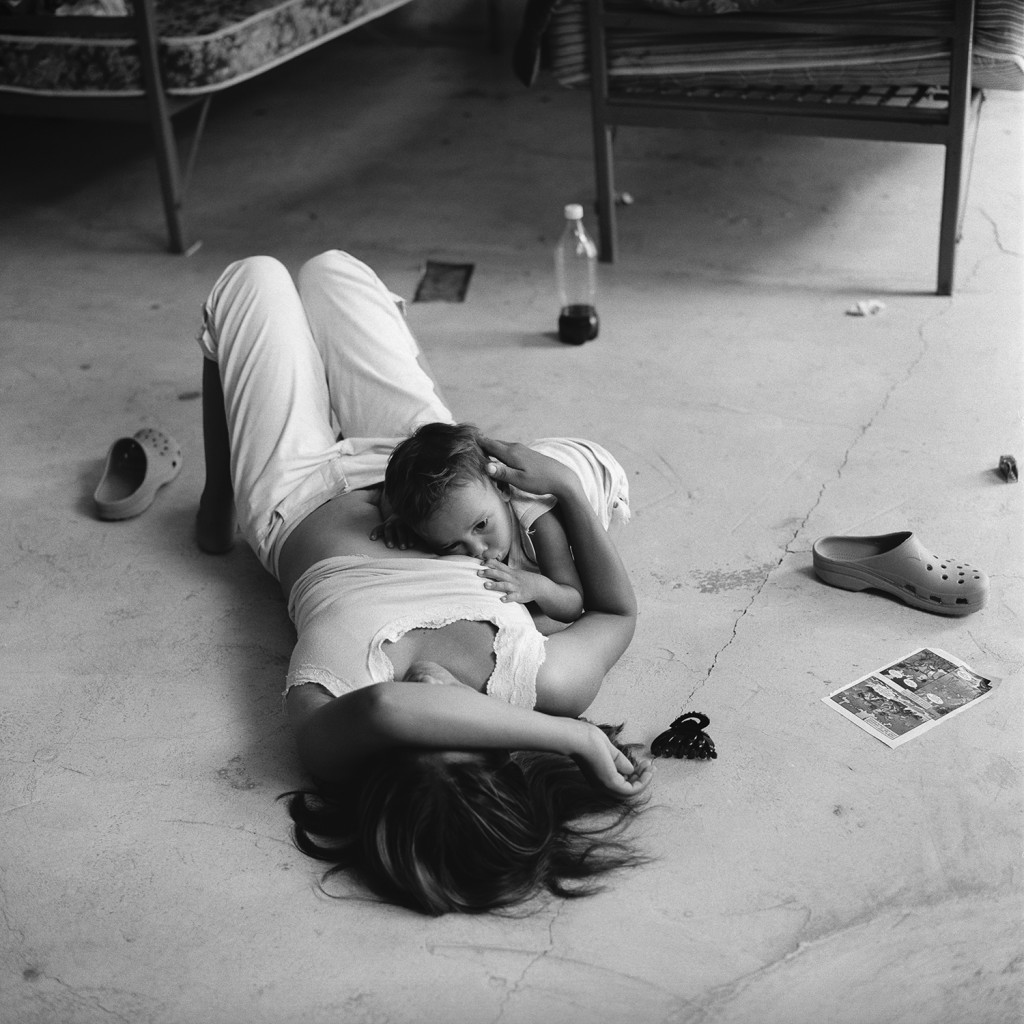

Some of your images show very intimate moments. How did you gain people’s trust to capture those moments?

It was staying there for days on end. Pictures that are frozen at a 60th of a second in time when we’re capturing an intimate moment or dramatic moment, 95 percent of what you’re doing day in and day out is waiting. You’re fighting boredom. That’s kind of their situation, as well. They’re always waiting for the train. There isn’t a train schedule. It comes when it comes, and you run for it. Other than that, it’s days on days of watching awful movies dubbed in Spanish and talking. It’s just a matter of time that you’re there and not taking photos at all. You’re talking; you’re listing. Once in a blue moon, you see something because you’re there.

You have one photo of a Guatemalan woman holding her 6-month-old. Someone said that was reminiscent of Dorothea Lange’s famous “Migrant Mother” photo from 1936. What do you make of that comparison?

That was from my last trip. I had that same reaction when I saw her there: “Wow. This is like that situation in the 21st century, and it’s kind of staggering.” I felt like I was seeing this iconic situation in real time. In the ‘30s when you had these displaced Okies streaming along southern California, they were probably greeted by yelling, too.

Why did you shoot this in black-and-white?

When I went free-lance, especially in the very early days, I stuck with black-and-white for all of my personal work, because from a practical standpoint, it was more cost-effective for me to produce. Because of the timeless nature of this story, I thought black-and-white was especially appropriate. I didn’t want the images to seem rooted in any particular time period.

What do you wish people understood about the situation you’ve been documenting for years?

I want people to know that, for the most part, they’re people who are leaving dire circumstances and weak governments and drug violence and domestic violence and poverty. A lot of the economic devastation that’s taking place in these countries is related to free-trade policies that have made it impossible to work or make a living.

July 2010

Most Local Unaccompanied Minors are Refugees

Up to 40 unaccompanied minors a year settle in Onondaga County. Unlike the recent surge of unaccompanied minors at the southern U.S. border, most children (under 18) who come here have refugee status.

“Seeking asylum after they’re here is a harder claim to make,” said Diane Chappell-Daly, a Syracuse lawyer who specializes in immigration.

To get refugee status, a United Nations staffer interviews the person to determine if the asylum-seeker experienced or is at risk of persecution based on race, religion, nationality, political opinion; are a member of a persecuted social population; or are fleeing a war. U.S. immigration officials also interview the refugees.

The U.S. accepts 55,000 to 77,000 refugees a year as part of an agreement with the U.N.

July 2010

“This is part of our international commitment,” Chappell-Daly said.

Beginning in the 1980s, unaccompanied minors from Vietnam came here. Since 2000, the county has welcomed refugees from nations including Sudan, other African nations and Burma. Daly said children as young as 10 have come here as unaccompanied minors.

Once here, unaccompanied minors are assigned a legal guardian, and the Onondaga County Department of Social Services finds them housing or foster families. The county contracts with Toomey Residential Services, a Catholic Charities program.

Finding foster families is the biggest challenge, Chappell-Daly said.

Most refugees speak little or no English and have little education. Many arrive after surviving severe trauma, and many are malnourished.

Many of the refugees are teens who may require a lot of attention, Chappell-Daly said.

“Younger kids have a better chance at assimilation, but have fewer ties to customs and language,” she said.

Chappell-Daly is not surprised at the partisan criticism about refugees coming to the U.S.

“There is an identity crisis every time there’s a wave of immigrants,” she said. “It creates fear Americans will lose their identity.”

Still, she thinks the recent debate – including the heated conversations about whether unaccompanied minors should have been housed temporarily in Syracuse – has been helpful.

“There’s more information getting out there about why kids are coming here,” she said.

• For information about becoming a foster parent for unaccompanied refugee minor children, call Michelle Maser at Toomey Residential Services: (315) 424-1845.

• Free immigration law clinic for low-income clients: First Tuesday of the month, 4 to 6 p.m., hosted by Refugee Resettlement Services, CYO Building, 529 N. Salina St., Syracuse. (315) 471-3409. Sponsored by the Volunteer Lawyers Project of Onondaga County.

February 2011

Michelle Frankfurter

-

www.michellefrankfurterphotos.com Personal: Born in Jerusalem, Israel; graduated from Jamesville-DeWitt High School and Syracuse University. She lives in Takoma Park, Md.

- Work experience: Staff photographer for the Syracuse Newspapers 1985 to 1988. Later worked as a free-lancer in Nicaragua for Reuters and with the human rights organization Witness for Peace. She has also worked for publications including The Guardian of London, The Washington Post Magazine, Ms., Time and Life Magazine.

- Awards: In 1995, a long-term project on Haiti earned her two World Press Photo awards. Her documentary work has been featured in numerous juried exhibitions.

- Learn more: www.michellefrankfurterphotos.com

- Get Destino: www.fotoevidence.com/bookstore

Renée K. Gadoua is a free-lance writer and editor who lives in Manlius. Follow her on Twitter @ReneeKGadoua.