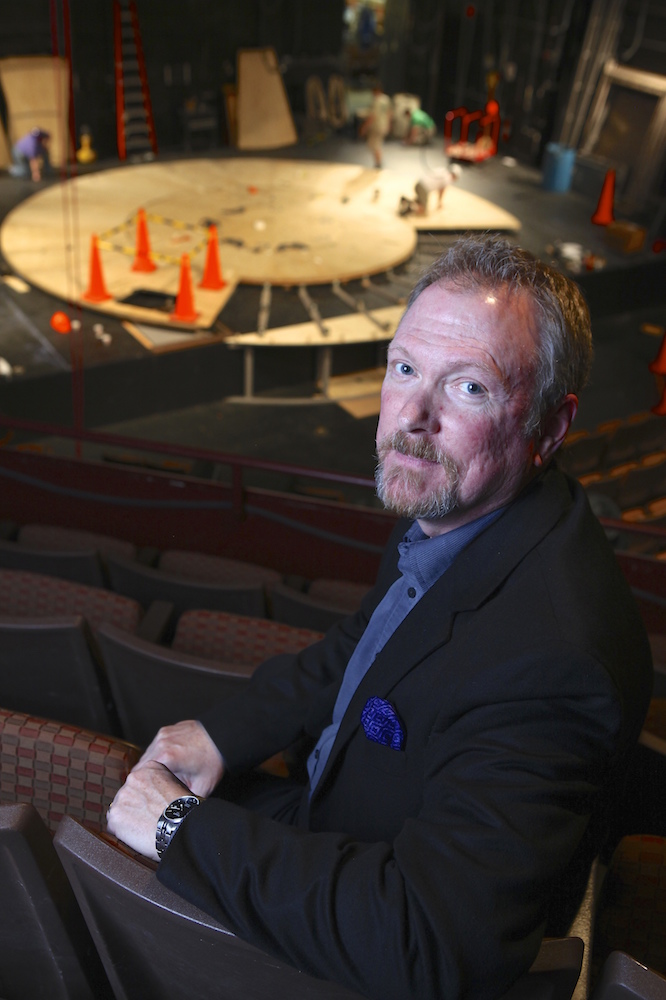

When blond, chin-bearded Robert M. Hupp, the new artistic director at Syracuse Stage, arrived in town he had to make some quick decisions about where to live. He says that one of the attractive features of the 44-year-old theater is its connection to a major university, but he did not elect to live near campus. Neither did he choose a leafy suburb, where many arts supporters reside.

Instead, in what looks like an attempt to slice through the curtain separating gown from town, Hupp and his wife, Clea Elaine Bunch, a Middle Eastern historian, opted for a downtown apartment on Warren Street. In what spare time Hupp can muster he wants to study local history at the nearby Onondaga Historical Association.

Some of those lessons in learning come from independent study. In the warm weeks of summer’s end, before the company ramped up for the new season, Hupp made forays into the local scene, showing up almost anonymously at cultural events, scoping out the crowds. Bob and Clea could be found amid the 1,000-plus crowd at the closing concert of the Skaneateles Festival in the Robinson Pavilion on Anyela’s Winery.

Hupp says his previous professional address, Arkansas Repertory Theatre, locally known in Little Rock, Ark., as “The Rep,” was “the biggest cultural attraction for hundreds of miles around.” He knew upon arrival that Syracuse Stage faces more competition for audiences and supportive donations.

After 17 years as the head of Arkansas Rep, the state’s largest arts organization, Hupp has plenty to say about achieving his artistic standards and presenting a rich array of theatrical offerings. Yet he is most passionate about the uniqueness of live theater.

“We crave communal experience, because we are often so isolated,” Hupp says. This is how the theater retains its vitality in a world of intense distractions. He puts the lure of storytelling first: “Theater is performance art with storytelling at its center.”

In an hour’s conversation, Hupp returns to the word “community” again and again in different contexts. While in Arkansas he reached out to small communities beyond the city, allowing some audiences to see professionally produced drama for the first time. Hupp says, “Artistic leadership means bringing the creative voice of the theater to the community. My philosophy of theater is tied to the idea that we have the rare opportunity to create important communal experiences for our audiences.”

Hupp’s views appear to be in harmony with the directions of Syracuse Stage. At one time “community” meant any opening night gala for a core of regular subscribers, many of them people associated with Syracuse University. Under the regime of previous artistic director Timothy Bond, quite different theatergoers were invited for dinner in the Sutton Pavilion on opening night. Audiences were chosen for their presumed connection with whatever show happened to be running, such as church groups for Lucas Hnath’s The Christians in April.

In welcoming Hupp to Central New York, former Syracuse Stage board president Louis G. Marcoccia emphasized, “Bob brings strong institutional experience and astute awareness of the varied roles the theater plays within the broader community.”

One of the ways that Hupp worked for a sense of community at Arkansas Repertory was to seek out stage works on local history. The most contentious moment in Little Rock history was the embattled racial integration of the public schools in 1957. Fifty autumns later, Hupp brought in Rajendra Rimoon Maharaj’s It Happened in Little Rock. Hupp remembers that the production provoked much discussion and soul-searching, and not just because so many of the original participants were still on the scene.

Syracuse Stage subscribers will remember Maharaj’s brief tenure, especially his secular Godspell, the 2008 holiday co-production with the Syracuse University Drama Department.

Hupp’s Arkansas Repertory continually welcomed new works, some of them with Central New York connections. Carla Vitale and Brett Smock’s musical version of Treasure Island premiered there in 2013. Its second production, directed by co-author Smock, appeared at Auburn’s Merry-Go-Round Playhouse in August. The last Arkansas work to appear on Hupp’s watch was last spring’s mounting of television writer Scooter Pietsch’s dark comedy Windfall, directed by Jason Alexander of Seinfeld fame.

Other premieres have enjoyed unmistakable regional appeal at The Rep. A hit of Hupp’s previous season was the opening of Duncan Sheik and Nell Benjamin’s Because of Winn-Dixie, based on the award-winning 2000 children’s novel.

When one looks at Hupp’s offerings at Arkansas Repertory, there is no signal of a sharp departure from what we have seen in the seven Timothy Bond years or in the 2016-2017 season that Hupp inherits from Bond. At The Rep he had scheduled Shakespeare, American classics, contemporary plays and musicals. He is untouched by Syracuse Stage founder Arthur Storch’s widely known aversion to the musical and can see scheduling one or two per season. “They are not bifurcated,” he stresses, not cordoned off from the non-musical dramas.

Hupp will also honor the company’s commitment to playwright August Wilson. He expects to complete the remaining three plays set in Pittsburgh’s black Hill District, decade by decade.

Hupp is reluctant to cite a single stage work he would never schedule but says he would avoid “the overproduced and the shopworn.” Classic theater interests him, but not as mere museum pieces. “What makes a classic timely?” he asks. “Can they be seen as bringing relevance to our lives?”

Before his move to Little Rock, Hupp was devoted mostly to works for select audiences that could include classics. From 1989 to 1999, he was artistic director of the Obie-winning Jean Cocteau Repertory in Manhattan’s East Village. The Cocteau was named for French poet, dramatist and polymath Jean Cocteau (1889-1963), a supreme modernist. Most productions were staged in the 140-seat Bouwerie Lane Theatre. Initial offerings included many works by Cocteau, in English, not French. Earlier directors had championed Greek drama and Restoration comedy.

Some of Hupp’s most notable successes were demanding modern works, such as the Eric Bentley-Darius Milhaud version of Bertolt Brecht’s Mother Courage and The Cure at Troy, an adaptation of Sophocles’ Philoctetes by Irish Nobel laureate Seamus Heaney, as well as Eduardo De Filippo’s realist comedy, Napoli Milionaria (filmed as Side Street Story). Six years after Hupp’s departure, the Cocteau Repertory morphed into The Exchange and still exists.

Despite Arkansas Repertory’s cultural dominance, and Little Rock’s being a state capital, Hupp is moving into a substantially larger operation here. The Rep’s annual budget for last season was $4 million while the one for Syracuse Stage next season will be more than $6 million. One of Hupp’s strongest assets for the search committee must have been that he increased the company’s subscriber base 100 percent.

In person, Hupp brings a comforting presence. He does not speak in elevated stage diction as did previous artistic directors Tazewell Thompson (1992-1995) or the Brooklyn-born Storch. Despite 17 years in the South, his default accent still evokes the East Coast, specifically Laurel, Del. (pop. 1,600), where he was born and raised. He fixes the questioner in his blue eyes, and answers in full sentences, never at a loss for words. Never facetious, he laughs easily and rolls effortlessly at teasing questions. He appears to suffer fools benignly and looks like a good man to send to a crowd that has never seen a stage play ever and is afraid to ask.

A director who has helmed both Seamus Heaney’s The Cure at Troy and Because of Winn-Dixie can bring us excellence in different costumes.

Season Schedule

The 2016-2017 slate at Syracuse Stage (820 E. Genesee St.; 433-3275) begins with Gale Childs Daly’s adaptation of Charles Dickens’ Great Expectations (Oct. 19-Nov. 6). Dickens’ classic Victorian novel boasts plenty of characters, but they will all be played by a half-dozen performers. Next comes the lavish musical Mary Poppins (Nov. 26-Jan. 8), the annual holiday co-production with the Syracuse University Drama Department. Choreographer Anthony Salatino and director Peter Amster will call the shots for this family treat.

The new year opens with controversy, as Ayad Akhtar’s Pulitzer- and Tony-winning Disgraced (Jan. 25-Feb. 12) addresses the timely issues of assimilated cultures. Ain’t Misbehavin’ (March 1-26) offers the pleasures of Tin Pan Alley composer Fats Waller. Memories of adolescence and incest key Paula Vogel’s 1998 Pulitzer-winning How I Learned to Drive (April 5-23), a co-production with Cleveland Playhouse. And capping the season is Ira Levin’s enjoyable puzzler Deathtrap (May 10-28).

A Jill Of All Trades

“Bob handles the plays, and I handle the spreadsheets.” With characteristic succinctness, this is how new Syracuse Stage managing director Jill A. Anderson describes the division of labor between her and the new artistic director Robert Hupp.

Amid the attention given the departure of previous artistic director Timothy Bond for Seattle, less notice was given to his managing director in those years, Jeffrey Woodward, who left in July 2015 for the Dallas Theater Center. The area’s premiere cultural institution thus launches its 44th season with fresh faces at the top.

In the earlier years of Syracuse Stage, the two people leading the company were described as the artistic director and the producing director. The semantic signal of Anderson as managing director is an expansion of her responsibilities, even to the purchase of paper products for the toilets.

At the center of that responsibility is supporting the artistic integrity of Syracuse Stage and its commitment to enriching the lives of people in the community. One of Anderson’s early tasks was to determine how one performance of the upcoming big holiday show Mary Poppins could be refitted for an audience filled with autistic children.

Managing an artistic enterprise calls for much more than accounting skills. Anderson began her life in the theater with the Mixed Blood Theatre company in Minneapolis. A Wisconsin native for whom allusions to the Green Bay Packers come readily, Anderson began her education at the University of Minnesota and completed her undergraduate degree at the University of Connecticut. Eventually she moved to Connecticut’s Eugene O’Neill Theatre Center, her last stop before Syracuse. She is also a member of the Actors’ Equity Association, a nod to the artistic side of her professional equation.

After bearing the burden of a company’s finances, Anderson can still find pleasure in performance. She is especially fond of dark comedies, notably those of Sarah Ruhl, known here for The Clean House and In the Other Room (The Vibrator Play), and also of Rhode Island-based Adam Bock. Some of his works, including Swimming in the Shallows, Drunken City and The Receptionist, have been produced locally, but not yet at Syracuse Stage. Lest this sound too rarified, Anderson is quick to speak of eclectic tastes. She swoons to remember Oscar Hammerstein II’s lyrics for South Pacific.

Since arriving in Central New York, Jill Anderson and her husband Dave Anderson have embraced Syracuse’s urban revival scene. They live within hailing distance of downtown’s Dinosaur Bar-B-Que. Jill Anderson speaks fondly of the easy access to gorgeous rolling countryside. It was only a short hop for the two of them to go apple-picking recently.

Dave Anderson is an electric bass player who grew up in orchestra pits as his father was a cellist with different symphony orchestras. He continues to work remotely for the Upton Bass String Instrument Company of Mystic, Conn., and looks forward to renewing his skiing habit on local slopes.