No other local performer enjoys greater authenticity on stage than does Gerard Moses. He’s a teacher of actors, an actor’s actor. As a Syracuse University Drama Department faculty member he took on more roles at Syracuse Stage than any colleague. Unlike other department members, Moses has also given generously of himself to community projects.

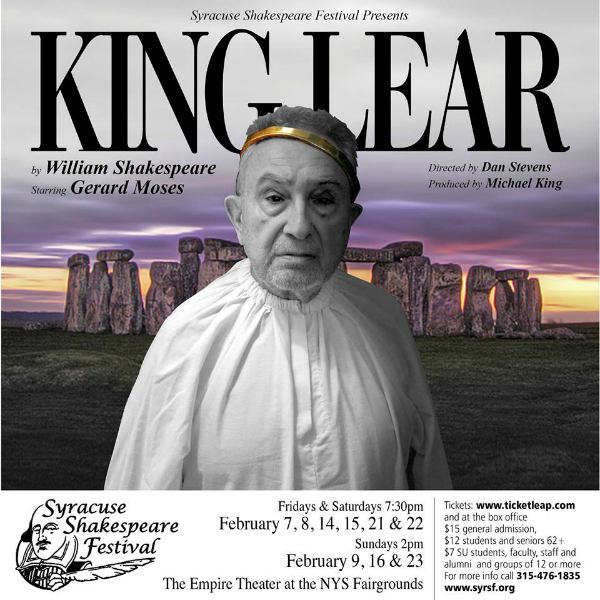

His presence in the Syracuse Shakespeare Festival production of King Lear, through Feb. 23 at the New York State Fairgrounds’ Empire Theater, draws in some welcome, rarely seen talent and raises some experienced players to new heights. In his own role Moses brings a world-standard professionalism: a misguided king of reckless power, folly and plangent pathos.

Moses brings a lifetime of concentration to this role, which he first played in his late 20s. Together with director Dan Stevens, he gives us Shakespeare in conversational American English. This is not a classroom production in which we’re supposed to admire a timeless classic but rather a community theater version emphasizing accessibility and clarity.

Moses’ default speaking voice tends to be soft, the rustling of dozens of feathers against silk. He employs it compellingly in the lengthy speeches later in the play, containing some of Shakespeare’s most admired poetry on regret, recognition and reconciliation. Along with wanting us to love these lines, Moses’ delivery underscores what the words mean to Lear’s evolving sense of himself.

This Lear comes in many colors. In the early scenes where Lear displays such reckless judgment and vanity, being cowed by his flattering older daughters, Goneril (Anne Fitzgerald) and Regan (Roxy Spano), and rejecting the honest young one Cordelia (Sharon Sorkin), Moses spurts angry vituperation. Because everyone in the theater knows this is Lear’s signal folly, there’s a temptation for actors to make this Lear a blowhard. Moses, perhaps conscious that he is shorter than your average Lear, stays away from inflated histrionics. Instead, the anger in Lear’s voice–that voice so refined, even dulcet later on–wields the lash against the innocent Cordelia.

As with Moses’ Lear, Cole’s Fool reflects decades of calculation, but that does not signal ponderousness. Cole’s Fool is taller, louder and more kinetic that the King. With his roseate robe, lace scarf and straw hat (thanks to costume designer Barbara Toman), the Fool might have been headed for a Maypole dance, eagerly grinning at the phallic imagery. He never lets an innuendo fly by unchimed and appears to have plumbed some we did not hear before. Yet Cole never neglects the Fool in the text: He speaks truths that Lear wishes to avoid.

The King’s three daughters are sharply delineated. Anne Fitzgerald, better known locally for comedy, is nearly unrecognizable as the dark-browed eldest, Goneril, a nasty girl with no need of showing her claws. Her threatened prowl is like watching movie actress Judith Anderson come back from the dead. Roxy Spano’s middle daughter Regan assumes a kind of girlish ingratiation to cover her villainy. Sloe-eyed Sharon Sorkin’s Cordelia is in no way impudent when she refuses to flatter her father, then goes smiling when she’s consigned to an arranged marriage with the King of France (Rahshon Glover).

Director Stevens cast familiar faces as the four disputing noblemen, some of whom break away from familiar personae. Mellifluous baritone Tony Bersani, a company regular but now beardless, energizes the baddie Cornwall. After marrying Regan he has license for vindictive sadism. Leading among his victims is the lean-limbed stalwart, the Duke of Kent (Tony Brown), who suffers shackles and a lost identity on Lear’s behalf.

Suffering deeper wounds is Gloucester (Bob Brophy), whose eyes are plucked out. Gloucester’s speeches have some superior poetry, and the character must negotiate the affecting scene where the blinded man encounters the half-mad king. Brophy, a frequent supporting player for many companies, has never had a better outing. Impressive also is longtime comic Lanny Freshman, reversing his usual type, as the clear-headed, take-charge Albany.

Stevens has cast two handsome hunks as Gloucester’s sons, the dour bastard Edmund (Nikolai Anatoli) and the sometimes spritely legitimate Edgar (Terrance Hartnett), whom we readily pair as siblings. Often seen as another iteration of Iago from Othello, Edmund is a malevolent schemer with big plans. Anatoli underplays him but could have used a bit more edge and cunning in his voice. Hartnett’s Edgar enters with all the insouciance of a hopped-up frat boy, badgering Edmund, but when threatened himself feigns madness as Tom O’Bedlam out on the heath. Hartnett is a charming performer throughout, but that’s not a quality we ascribe to Tom O’Bedlam.

Opening night suffered continuing problems with sound, beginning with the selection of well-known pieces of music, such as Verdi’s “Requiem,” which tag along emotional associations from other contexts. During the scene of reconciliation between Lear and Cordelia, the piped-in choral music drowned out the soft-spoken dialogue, exacerbated by blocking that interrupted sightlines. In all, though, Gerard Moses’ King Lear is one of the strongest performances the Syracuse Shakespeare Festival has ever given us.