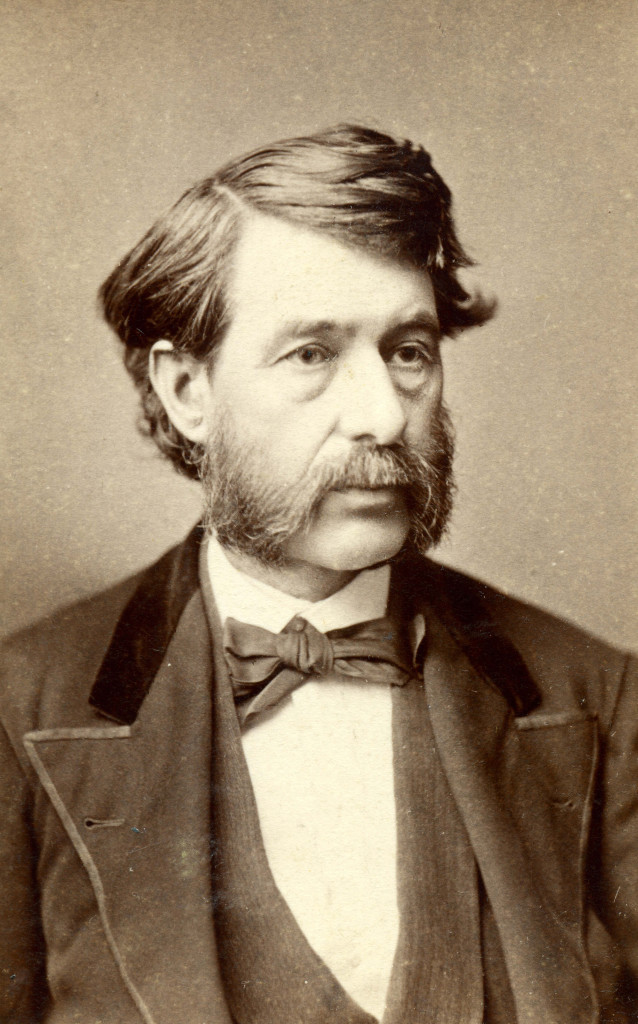

George Barnard, one of Central New York’s own, has slowly gained recognition as among the most important pioneer photographers in documenting the tragedy of America’s Civil War. A 2013 exhibition on Civil War photography at New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art included an entire gallery devoted to Barnard’s work. In November, the Washington Post’s magazine featured an article on war photography titled “Pioneers of the Form.” It highlighted the four Civil War photographers generally acknowledged as the most significant in that field: Matthew Brady, Timothy O’Sullivan, Alexander Gardner and George Barnard.

Before the war, Barnard had studios in both Syracuse and Oswego and captured some of the earliest images of Syracuse with his camera. Around 1859, he began contract work for larger studios based in New York City, which brought him into the orbit of Mathew Brady.

Brady assigned him to Washington, D.C., just as the Civil War broke out. Barnard captured some of the first photos of the Bull Run battlefield. Later in the war, he was hired by the Army to document military structures and fortifications in the western theater. In 1864 and 1865, this afforded him the opportunity to include the impact of warfare as Gen. William Tecumseh Sherman’s troops marched through Georgia and the Carolinas.

After the war, Barnard was able to use these images, and further photos of key locations, to assemble a major portfolio documenting what became known as Sherman’s “March to the Sea.” That portfolio of work, published in 1866, is considered one of the historic milestones in the development of landscape photography.

Barnard went to New York City to work on the production of this book, but he also resided for periods in Syracuse, on North Townsend Street, just behind Assumption Church. He still had family connections here. Barnard then decided to relocate to Charleston, S.C., in 1868. The nation had interest in the Reconstruction effort and the South’s future. Barnard saw an opportunity to record that.

His work was successful, but his sojourn in Charleston was interrupted with another move, this time to Chicago to be near his sister Mary. Her husband, a successful businessman, offered to underwrite the establishment of a studio there for Barnard. He moved to Chicago in 1871, just a few months before it was devastated by fire.

The Great Chicago Fire burned for two days, killed up to 300 people, consumed more than 2,000 acres in the heart of the city and left about 100,000 people homeless. Barnard ran to his studio to save some items from the raging fire. Like others, he then headed for Lake Michigan in advance of the flames and waded into the water, holding his equipment over his head.

The destruction of Chicago was unbelievable, and the nation was instantly hungry for images of the desolation. Many photographers flocked to the city; Barnard was already there and soon produced 63 stereo views.

Although less known than his Civil War work, these Chicago Fire images stand today as an effective blend of both the documentary and aesthetic talents of Barnard. Like his Civil War portfolio, these photos show an imaginative use of composition.

He framed a view of the burned-out courthouse through a series of cast-iron arches from across the street. In another photo, the stark remains of the Congregational Church appear like an abstract sculpture. The Onondaga Historical Association owns a complete set of these stereo views and an original copy of his highly valued Civil War portfolio.

Barnard later returned to Charleston, documenting more scenes of the “Old South”: its churches, landmarks, historic landscapes and citizens. His photos of African-Americans at the time, both in studio portraiture and documentation of their plantation experiences, constitute some of the best known views of mid-19th-century black life in the South.

The 1880s found Barnard in the Rochester area as one of George Eastman’s earliest employees, working to promote Eastman’s revolutionary dry-plate technology. Eastman’s entrepreneurship led to the creation of the Kodak empire. Barnard, however, moved on. He tried his hand at manufacturing dry-plate equipment near Cleveland and, in a possible nod toward retirement, relocated with family to a farm in Alabama, but just for a few years. By 1893, Barnard moved to an in-law’s farm in the Cedarvale section of the town of Onondaga.

There, Barnard lived out the final years of his life. He died in 1902 and is buried in a small cemetery along Pleasant Valley Road, just east of Marcellus.

OHA has conducted extensive research on Barnard and assembled an important collection of his work. Much of Barnard’s photography, spread over the “seasons” of his life, is on exhibit at OHA’s museum through August in a show titled Ever A New Season: 19th Century Photographer George Barnard. For information, visit www.cnyhistory.org.

Dennis Connors is curator of history at the Onondaga Historical Association.