At the ArtRage Gallery, Blackout: Through the Veiled Eyes of Others. Racist Memorabilia from the Collection of William Berry Jr. investigates racism by displaying a series of household objects stereotyping African Americans. These are mass-culture items purchased and used by everyday households.

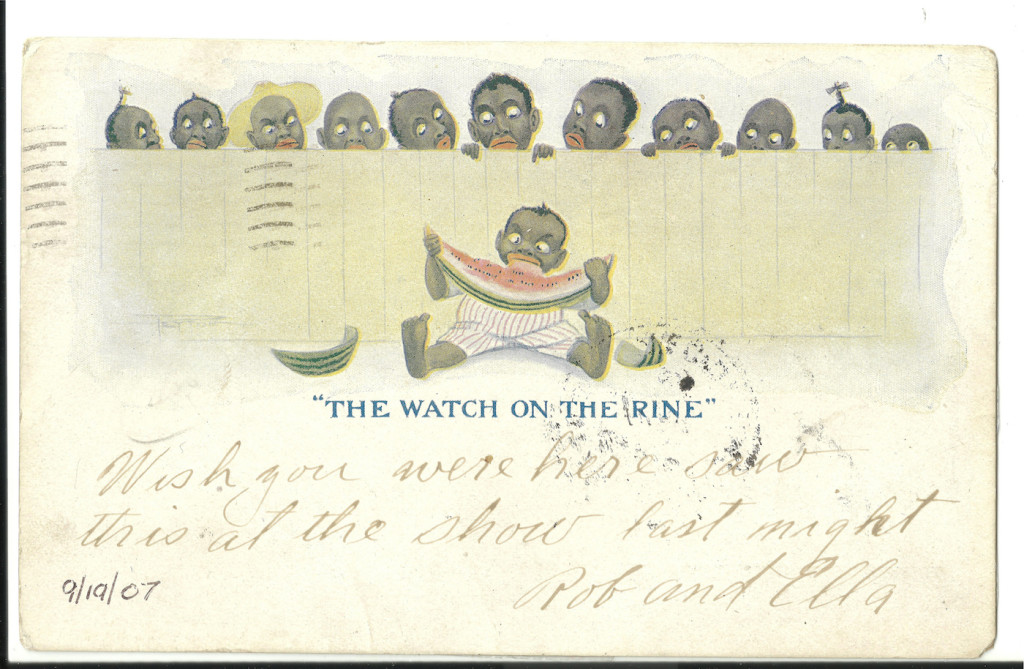

Indeed, the exhibit presents a range of artifacts: “Jolly Nigger Bank,” whose subject has outlandish lips and other distorted features; “Darkie,” a top-selling toothpaste in Asia until a name change in 1989; a ceramic ashtray from roughly a century ago based on an ideology perceiving anyone of African descent as subhuman. There’s also a postcard published just after 1900 that depicts an alligator chasing a young African American up a tree. That event is seen as humorous.

Blackout, selected from a collection that Berry began during the mid-1970s, includes well-known objects like an Aunt Jemima syrup dispenser from 1960 and more obscure items. It encompasses a postcard mocking an African American minister, a “Red Cap” picnic jug from the 1940s, and material regarding Coon Chicken Dinner. Three restaurants with that name operated in Utah and other Western states. Each of them had a stereotypical figure, representing African American men, at their entrance.

These, and other objects, are presented in a gallery context and accompanied by captions that both identify a particular item and discuss development of stereotypes. For example, the text about the aforementioned ceramic ashtray references the work of anthropologist Madison Grant. In 1906, he displayed Ota Benga, a Congolese Pygmy, in a cage at the Bronx Zoo, in proximity to apes. Grant was an individual with academic credentials who held highly racist views.

Another caption discusses the evolution of the Uncle Tom stereotype. In the novel Uncle Tom’s Cabin, there’s a hardworking, highly ethical character who strives to maintain dignity even while he’s enslaved. In the stereotype, anything positive is torn away, and he’s reduced to a groveling figure.

And the ArtRage show highlights the absolutely ordinary nature of the products on view. There’s nothing unusual about Gold Dust, a household cleaning product. Yet the manufacturer centered an advertising campaign on “Goldie” and “Dusty,” two stereotypical characters.

The objects on display access and illustrate a belief system with racism at its core. Although many of them were first sold in stores long ago, the exhibit isn’t intended to be purely historical in scope. There are three remembrances in which Berry recounts incidents from his own life. In the first, as a young child visiting Florida, he attended Mass at a Roman Catholic church. When he stepped toward the altar to take communion, an elderly man shoved him aside.

In reflecting on the exhibit, Berry said he understands it will be a difficult show for some viewers. However, he notes that it places the memorabilia in a safe space, in a gallery where people can view the objects and consider their significance today. Even more importantly, Berry hopes the show “will open up dialogue, an open, frank conversation about race and racism.”

Berry, a retired educator who worked as an administrator at various schools including Cayuga Community College and SUNY Stony Brook, will give a gallery talk at ArtRage on March 10 starting at 7 p.m. That’s just one of several events hosted by the gallery over the next three weeks. For more details, see the sidebar on the facing page.

ArtRage Explores Minstrel Show Tradition

By Russ Tarby

Although now scorned by mainstream critics, minstrel shows dominated American entertainment during the 19th century. Initially performed by white actors in blackface, the genre was adopted by African American performers in the 1850s. These enterprising Negro entertainers willingly played the grinning black fool to entertain audiences of all races.

“We now consider minstrelsy an embarrassing relic, but once blacks and whites alike saw it as a black art form, and embraced it as such,” write researchers Yuval Taylor and Jake Austen in their 2012 book, Darkest America: Black Minstrelsy from Slavery to Hip-Hop.

The authors make a strong case for black minstrelsy’s deep relevance to contemporary black entertainment, particularly in the work of popular artists such as Dave Chappelle, Flavor Flav, Spike Lee and Li’l Wayne. Darkest America explores the origins, heyday and present-day manifestations of this tradition, exploding the myth that it was a form of entertainment that whites foisted on blacks and shining a controversial light on how such performances can be demeaning but also, paradoxically, liberating.

Booklist critic Vernon Ford wrote that Darkest America traced minstrel traditions well into the 20th century on radio and television shows such as Amos’n’Andy The Jeffersons, Good Times and The Cosby Show. “They note that Bill Cosby’s sitcom and other shows were counterpoints to contemporary minstrel shows,” Ford wrote. “Yet Cosby in his earlier cartoon show presented characters that appeared to embrace the old-time minstrels.”

Central New Yorkers can reflect on this checkered entertainment history when ArtRage Gallery, 505 Hawley Ave., presents a free screening of director Spike Lee’s 2000 satire Bamboozled on Wednesday, Feb. 17, 7 p.m. The plot revolves around a frustrated African American TV writer who proposes a blackface minstrel show in protest, but to his chagrin it becomes a hit. The movie stars Damon Wayans, Jada Pinkett Smith, Paul Mooney and Michael Rapaport.

On Thursday, Feb. 25, 7 p.m., ArtRage presents pianist Dick Ford performing a program called “Blackface! Race: The American Obsession Nurtured and Affirmed Through Popular Music (1850-1940).” Admission is free.

The founder of Signature Music in Syracuse, Ford will lead a discussion and play songs ranging from the Civil War era to the Roaring ’20s, and will display more than 100 racist images from sheet music that helped popularize racism in our culture.

His talk will touch on the phenomenon known as “coon songs,” a genre of music that relied on stereotypical and often demeaning images of African Americans. In fact, the biggest hits of the ragtime era weren’t Scott Joplin’s stately piano rags. Instead, coon songs such as “Every Race has a Flag but the Coon” and “Coon on the Moon” defined ragtime for the masses. Although such titles may offend modern ears, it’s impossible to investigate black popular entertainment of the 1890s without directly confronting the coon songs that clearly presaged the original blues.

Ford will also discuss songs such as “Darktown Strutters’ Ball,” written in 1917 by black Canadian composer Shelton Brooks.