In a mid-1970s Berkeley Barb article about the activities of the Weather Underground, the most radical of that generation’s Caucasian social activist organizations, co-founder Bernardine Dohrn, was quoted, “One day you’ll wake up and look out your window. And there on your front lawn will be a great flaming W and you will know the time has come for you to be a Weatherman.”

In a recent telephone interview she chuckled relating a contemporary irony. “If they passed by my house in Chicago today, they would see a big W in an upstairs front window. It’s for the Cubs, reflecting on a brief moment of ecstasy (the World Series triumph). And then we got Trump.”

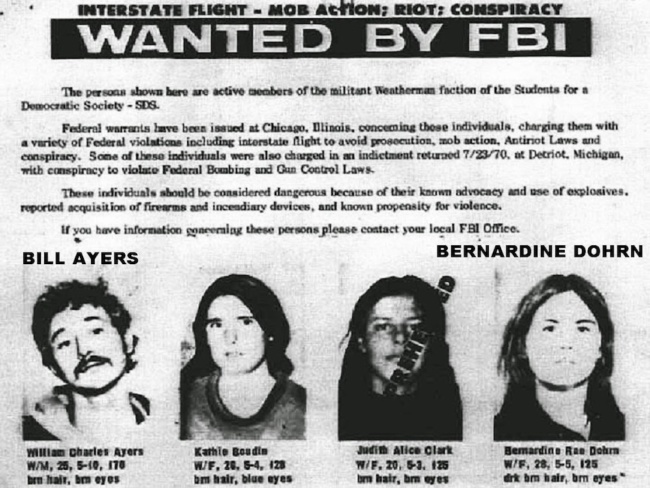

Her comparative reflection on social activism then and now, however, found more similarities than differences. Once labeled by the late FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover as the most dangerous woman in America, Dohrn noted that to get some indication of people’s current concerns she recently leafleted her block, calling for a meeting to discuss social issues.

“Thirty people came,” she said. “Everybody was doing something.”

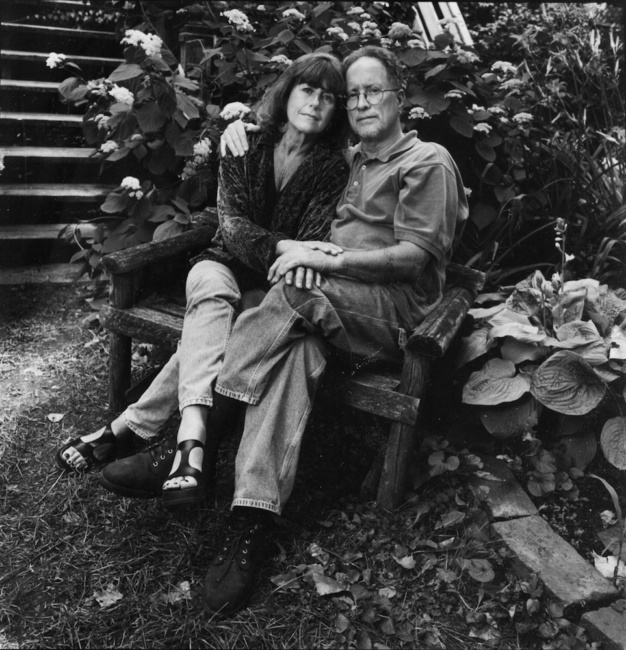

Dohrn will be talking issues herself, with her husband Bill Ayers, also a Weather Underground co-founder, on Wednesday, May 24, 7:30 p.m., at The Other Side, 2011 Genesee St., Utica, next door to the Café Domenico for a session of the newly instituted Big Conversation series. Tickets are $10 for adults, $5 for students; for reservations, call (315) 735-4825 or e-mail to [email protected].

Café proprietors Kim and Orin Domenico hope the series will become an inspiration for discussions of social action issues, with the potential for inspiring some action itself. They plan to host four speakers each year, with one being of national significance. Syracuse Peace Council veteran Ed Kinane set a tone for the locals when he kicked off the series opener.

Dohrn and Ayers have both retired from college teaching but still work as adjuncts in the Chicago area. Dohrn, who once served nine months in jail for refusing to cooperate with a federal grand jury, works on prison issues.

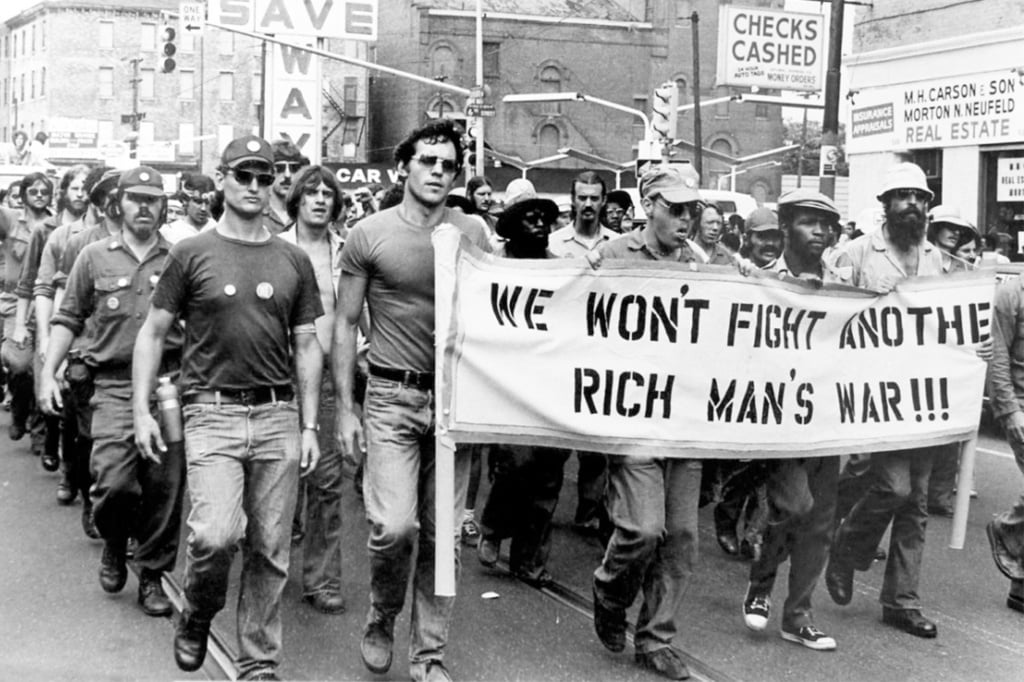

Dohrn is enthused by a variety of indications of resistance to President Trump, especially the turnouts to women’s marches. Recalling “The Movement” of activism half a century ago, bringing together groups seemingly diametrically opposed in philosophy, the women’s movement, along with an LGBT movement and one focused on climate issues, she sees as resurgence taking root in a labor movement generated by domestic labor and health workers.

She has a sense that common longings will foster that resurgence, and that currently across the country discussions are beginning to explore actions that can be taken. She feels that the country’s democratic system can be utilized to achieve equal rights and empower the disenfranchised.

“We can’t not use it,” she says. “But the radicals and activists of today have to understand what works inside the system and what has to work outside the system.”

Locally, the stories of two young people demonstrate the impact of the Weather Culture. Naomi Jaffee came to town in the mid-1960s, in a flowered cotton dress, with stockings, high heels and a scarf in her hair. A Syracuse University graduate student, she worked through the School of Social Work as a researcher at the Community Action Training Center, the largest community organizing project of that era’s War on Poverty in the country.

Her evolution in style to black turtleneck, blue jeans and sandals broadcast a reaction to the sense of change she came to personify, a merging of ideology and lifestyle. When the training center was crushed as a threat to the powers that be, local and federal in direct connection, Jaffee was visibly hardened by the experience.

She left town but returned on an FBI wanted poster on a post office wall citing her for consideration as “armed and dangerous.” By that time the Weather Underground’s several factions had begun to splinter in open conflict. “They should consider us ‘armed and terrified’” one leader defined the state of things, “or ‘armed and incompetent.’”

The case of Susan Stern started with some similarity. She came to the campus, admittedly, to find a husband. As with many of her generation, she found a husband with a rapidly expanding political consciousness.

Within five years her own consciousness was dominated by Weather Underground thinking. She left Syracuse after being fired for encouraging her sixth-grade students to send less-then-diplomatic letters to the mayor. She echoed the group’s rhetoric at every meeting she attended in her adopted hometown of Seattle, but when a collective formed there, she was accepted — only to be kicked out for not fitting in.

She recalls the experience starkly. “The weight of the underground loomed over us with devastating certainty,” she says. “There was no escape. No heroism, no splendor, no glorious revolution, no marching bands and banners. We were just on the verge of learning that revolution is more than hard and greater than human.”