A woman with years of experience as a social worker in Syracuse tells a story of a mother sleeping with her newborn baby in bed between her and the baby’s dad. The baby suffocated because of the heat of the parents’ bodies and the heat of the room.

The bereaved mother later told the social worker that a staffer with Onondaga County’s Department of Social Services came to her home. Without offering condolences for the couple’s loss, the worker began opening cupboards and drawers, apparently looking for drugs, because the mother had a documented history of drug use.

Several longtime experts working with Syracuse’s most vulnerable families told the Syracuse New Times similar stories last week. While none of the stories can be verified, they suggest a deep-seated perception that the Department of Social Services (DSS) is unsympathetic and punitive, with a primary goal of taking children away from their parents. The result, experts say, is that many families most in need of education and assistance might resist aid if they think it is connected with DSS.

The apparent disconnect between the county’s well-intentioned efforts to help families and the perception that DSS polices behavior reflects one facet of what former county Health Commissioner Dr. Cynthia Morrow has described as an “unintended consequence” of Onondaga County’s possible reorganization. Morrow resigned as health commissioner early this month because she disagrees with the county’s plan to move its maternal and child health services into the county’s Department of Children and Family Services.

The county in 2013 began a reorganization of all its human services to offer more streamlined service to families. The Department of Social Services-Economic Security (DSS-ES) provides public benefit programs. The Department of Children and Family Services provides casework programming related to child welfare, mental health, school-based services and juvenile justice, including Hillbrook Juvenile Detention Center. The county also created the Department of Adult and Long Term Care Services.

Reorganization of the county’s Health Department would continue to make access to services less confusing, according to county officials. The Health Department oversees programs including nutrition and healthy food support (WIC), home visits for new mothers and Healthy Start. No change will occur until at least the 2015 county budget in the fall, said Onondaga County Legislator Danny J. Liedka, R-East Syracuse, who is chair of the county legislature’s Health Committee. He said Morrow’s resignation was premature because no formal proposal has been made.

“They are not going to put this in if they think it’s going to jeopardize families and children. That’s that,” he said. “They’re certainly not going to do it if it’s going to jeopardize funding.”

But fears and criticism are strong among some in the health care provider community. They worry about funding, and one woman with years of experience as a social worker and health educator declined to speak on the record, saying she feared she would lose her job if she were candid.

Elizabeth Crockett, executive director of Reach CNY, is worried about losing money. Reach CNY is an independent agency that contracts with Onondaga County to provide two programs: the Syracuse Healthy Start Consortium, which seeks to improve maternal child health and eliminate disparities in infant mortality in Syracuse; and a perinatal program, which provides pre- and perinatal services, such as breastfeeding support and education about safe infant sleep. County grants pay for four employees and 15 percent of the executive director’s salary.

“We rely on that money,” Crockett said. “What we don’t know is whether the new design will need to be looked at by the state and federal governments.”

Crockett echoes the concerns of Morrow and other medical experts who see child and maternal health services as a core public health function.

“Healthy Start has community input as part of it,” she said. “That’s why it would have been important to talk to the public first. It’s so hard for us to understand why it would make sense to take some of the direct services and move them, because they depend on other services we offer.”

The public health structure, she said, “is so valuable and has evidence behind it and it’s effective.”

Crockett and others fear that a stigma associated with DSS – the name most still use, despite the county’s reorganization – could undermine trust between families and providers and slow or reverse progress in areas such as infant mortality and premature birth.

A pregnant 15-year-old is influenced by her family and friends, said the worker afraid to speak on the record. “They see Social Services as the enemy,” she said forcefully. “They say, ‘They’ll be in your business and take your children.’ It’s a history of what CPS (Child Protective Services) is.”

She and several others interviewed conceded that sometimes social workers have to remove children from a home to keep them safe. And most of those interviewed said Child and Family Services workers are well-trained and committed to helping families. But the consensus is that for many families, a visit from DSS or CPS makes them defensive and less likely to seek aid for fear of being judged or punished.

“We are going to lose clients because of that connection,” the worker said. “Moms who need to get prenatal care are not going to get care as early. It’s a real concern. They (the county) don’t know what people are really living.”

Evelyn Kinsey, a member of the executive council of Syracuse Healthy Start and a longtime social worker who works at Jewish Family Services, was blunt about the deep suspicion and fear many city families hold for anyone connected with DSS.

“If the mom had to go to WIC to get prenatal care and other services she may need, she may fear that her child might be taken away,” she said. “Say she indulges in smoking marijuana and crack cocaine. You think she’s going to go down there?”

Kinsey points out that healthy babies save money.

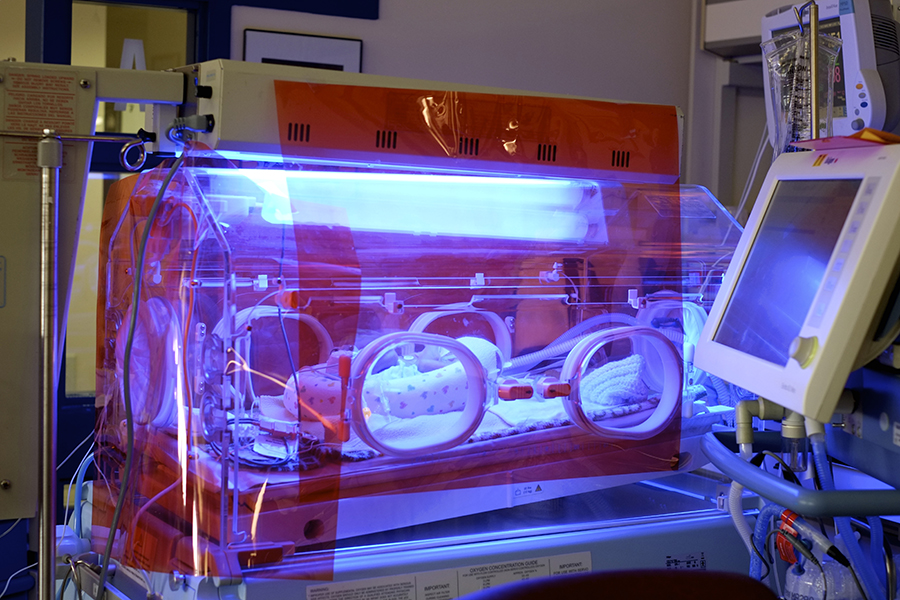

“If our moms are healthy, there’s a strong possibility our babies are healthy,” she said. “If the baby is born and the mom is addicted to drugs and the baby is addicted to drugs, that’s a burden to all the taxpayers. If you bring a sick baby into this community, underweight and hooked on drugs, in the NICU for six months on all kinds of tubes and machines, who pays for that?”

Kinsey said experience shows that social workers visiting a home are often met with suspicion and fear – if the parent even opens the door.

“That mother automatically goes in the defensive mode,” she said. “She thinks, ‘What did I do wrong? I don’t want those people here. Why is she coming here for?’”

Dr. Michelle Bode, a neonatologist at the Regional Neonatal Intensive Care Unit at Crouse Hospital, in Syracuse, treats many of the city’s sickest infants. The increased use of prescription painkillers (codeine, hydrocodone and oxycodone) among pregnant women is just the latest challenge for the vulnerable families she treats. New babies going through drug withdrawal often end up at Crouse’s NICU.

“My worry is these women won’t tell us they are using a narcotic,” Bode said. “They may not think it’s a problem because it was prescribed. They might be afraid to tell us.”

Patients fear the stigma of drug use and don’t want to be under the supervision of DSS, she said. If trust declines, so will early intervention, she said.

“Are we going to see a drop in prenatal care done early? Are we going to see a rise in the rate of infant mortality? It might not be direct cause and effect, but it sure is going to be looked at,” she said.

“There’s a real fear,” Bode said. “The word ‘DSS’ strikes fear in families. Period.”

“The language pushes buttons,” she said. “It’s an important cultural fear to acknowledge.”

She cited the Tuskegee syphilis experiment, in which the U.S. Public Health Service studied the progression of untreated syphilis in African-American men, as one source of mistrust. More than 400 men infected with syphilis went untreated for decades in a federally financed experiment in Alabama.

“It was terrible,” Lane said. “One of the worst fallouts was it left people of color fearful of using medical care.”

That’s one reason Healthy Start did not call itself the health department, she said. But she also called DSS workers “quite reasonable and deliberative. They were not trying to take children away quickly.” And when children did have to be taken from dangerous or neglectful homes, they “acted with professional concern,” Lane said.

She does see merit in consolidating all county maternal and child services. For example, many women experience depression in pregnancy and after pregnancy.

“Having perinatal care and mental health services linked together would be a great thing,” she said. “Pregnant women might have multiple needs: housing, shelter from domestic violence, drugs, she might need smoking cessation, lead poisoning assistance. … Anything that can help coordinate those services would be good. The more we could integrate them, the better it would be for the people, and there might be cost savings.”

Lane hopes the county reorganization creates an integrated data system.

“We have about 2,200 births a year in Syracuse,” she said. “Many of the people with the greatest health challenges live in the city. Two thousand two hundred is not too many to coordinate if there was software and training and capacity to follow these kids so when a public health nurse goes out to the home, they might get information about other services. Think how efficient it could be.”

The bottom line, Lane said, is, “if it’s done well, the potential good outweighs the potential bad. I understand where that fear comes from. But when the decision has been made to coordinate services, we have to take that fear and deal with it. It’s very possible to change perceptions.”

She suggests a public relations effort to address the fear, and meetings at churches, faith communities and community centers.

“They need to talk about it with the families,” she said. “They need to be clear, ‘This is what we’re trying to do.”

Kinsey, the longtime social worker, remains skeptical.

“They really need to think this through before they vote,” she said. “They really need to get the community’s take on this. They need to talk with the mothers. They’re the ones that are going to be affected.”

Increased Painkiller Prescription

At-risk families face a new challenge. U.S. doctors are prescribing opioid painkillers to about one in five pregnant women who receive Medicaid benefits. That means more babies could be born addicted.

Onondaga County has the highest rate in New York of hospital discharges of newborns with drug-related problems, according to the state health department. In New York, 6.9 of 1,000 newborns have drug-related issues; in Onondaga County, the rate is 26 of 1,000 newborns.

That sharp difference can be explained by the fact that all babies born in the regional NICU are recorded as being from Onondaga County, while the region stretches much farther. Still, Dr. Michelle Bode, a neonatologist at the unit, is concerned about the trend, and worries that pregnant women might not disclose to their caregivers that they are taking prescription painkillers.

Mothers who use these narcotics – even if only for a few weeks, risk giving their babies Neonatal Abstinence Syndrome – otherwise known as withdrawal.

Video Source: https://nccnews.expressions.syr.edu/2014/02/babies-with-withdrawal-symptoms/

What’s at Stake?

Here’s how the Onondaga County Health Department describes its Maternal and Child Health services:

Division of Maternal and Child Health (MCH) is made up of programs that target at-risk infants and children, new moms and parents, as well as their families. These include the Departments of WIC, Healthy Start, Immunizations, Special Children Services and the Bureau of Community Health Nursing. Services provided include home visits by nurses, outreach workers, and social worker to maternal/child clients for health assessments, case management and consultation, preventive teaching, as well as facilitating access to medical care and referrals for indicated community agencies and services. We concentrate our efforts to reach first time pregnant women and those at highest-risk for infant mortality, low birth weight, and developmental delays or disabilities. MCH strives to promote a healthier maternal/child community and to eliminate healthcare disparities. MCH tailors all client services to meet the differing needs of each individual and family. For more information about the Division or to make a referral, call 315-435-2000.

What the County Says:

David Sutkowy, commissioner of the Department of Children and Family Services:

Last year, during the budget process, we realigned services because many people were receiving services across departments. It was so hard for families. We could do better. It was just very confusing to a lot of people. We thought we could make care connections far better.

The services that are being provided through Child and Family Services are voluntary. People access mental health services voluntarily. … We talked to many families. They were appreciative that we were doing this. No one thought doing this would have a chilling effect.

In the child welfare system, half of the families currently receiving child welfare services are participating on a volunteer basis. They have come into the system and see us as a help. These are families that trust us.

Our planning is by no means done on this. I did contact some other counties that are organized this way. I asked them if they have any evidence through data or anecdotes that there is a chilling effect on seeking services. The answer was “no.”

Ann Rooney, deputy county executive for human services:

They’re reacting to something that is not part of our thinking. They would become a part of Child and Family Services. They are not the same program.

You have spoken to people on the medical side. The human services providers have not made that accusation. This idea that physical health is somehow segregated from the whole of health of the child is one that should not be promoted here.

Ben Dublin, Onondaga County executive’s chief of staff:

If something is happening that is inappropriate under the current program, under Healthy Families the nurses are mandated reporters. They are obligated to elevate it. To say these same people under a different organization will act differently is just wrong. That’s underestimating the clients.

The Onondaga County Health Advisory Board meets quarterly to advise the commissioner of health on matters regarding the preservation and improvement of public health and public services throughout the county. Members are:

Chair – Thomas H. Dennison

Mary Beth Carlbert, MD

Larry Consenstein, ND (NICU at St. Joe’s)

Ruben Cowart, PDS

Peter Cronkright, MD

Ann Rooney, deputy county executive for human services

Diane Turner, mayor’s appointee

Monica Williams, Onondaga County legislator representing the 16th District, which includes the Southwest Side, Outer Comstock and University area

Lawmakers Discuss Objections to Proposal

The Health Commission held a special meeting April 11 to address Dr. Cynthia Morrow’s concern about the proposal to move the county’s maternal health programs in the county’s Department of Children and Family Services. CLICK HERE to read minutes from the meeting