It’s an old, old building with new curb appeal. At base a remodeled 1914 movie house, Syracuse Stage’s Archbold Theatre has long been a familiar fixture on East Genesee Street, downhill from the Syracuse University campus. It looks different now, though. During the six-and-a-half year tenure of producing artistic director Timothy Bond, it has become a prime station on the Connective Corridor.

White paint now covers the wide façade with the new logo, an emerging red disc, featured prominently. Three structures, including the Storch Theatre at left and classroom space at right, now embrace a continuous whole. Over the front door stands a Japanese torii-like dark red arch. Opposite stand eight, tall mesh panels at oblique angles. Behind them lies an angular walkway of different colored tiles, 30 of which are dark red. By standing on certain tiles, not all of them, you trigger a hidden loudspeaker broadcasting a cannon shot or chimes. Abandon dull care, ye who enter here.

Bond arrived from the West Coast in September 2007, the third year of the Nancy Cantor chancellorship. He has said from the beginning that Cantor’s vision of SU’s relationship to the community was primary in his finding the Syracuse position attractive. Her continued support of Bond’s work encouraged him to try new plays that otherwise might have difficulty reaching an audience, such as Wajdi Mouawad’s drama Scorched last fall and David Henry Hwang’s comedy Chinglish, opening in late February.

Smiles from the chancellor’s office allowed Bond to achieve one of the happiest moments of his time with Syracuse Stage, when he took his production of Tarell Alvin McCrany’s The Brothers Size to the Baxter Theatre of Cape Town and the Market Theatre of Johannesburg, South Africa. The current mission statement for Syracuse Stage speaks of aspiring to a global village square.

As writer Walt Wasilewski pointed out in the Dec. 11 Syracuse New Times cover story, the whole of Nancy Cantor’s legacy is still the subject of debate as well as cocktail party argument. Her benign influence at Syracuse Stage, in reality the SU Theatre Corporation, is more assured. Cantor’s call that SU sees itself as a national rather than a regional entity was well received by Bond and his managing director, Jeffrey Woodward, formerly of the McCarter Theatre in Princeton, N.J.

In the current regime, familiar, audience-pleasing works like Noel Coward’s ever-stylish Blithe Spirit or the ultimate warhorse, A Christmas Carol, will still receive respectful, energetic presentations. But again and again Bond-era productions aim for resonance beyond the reaches of East Genesee Street, even to South Africa.

August Companion

In his many successes, Bond builds upon rather than breaks with the legacy of his predecessors. The late Arthur Storch, who founded Syracuse Stage 40 years ago this month, fostered several American and world premieres, the most memorable of which was Patrick Meyers’ mountain-climbing philosophy debate K2 (April 1982). Robert Moss’ staging in sequence of the two parts of Tony Kushner’s Angels in America (January 1998) drew audiences from all over the Northeast, while his version of Nigerian Nobel laureate Wole Soyinka’s poetic and mythic Death and the King’s Horseman (February 1999) attracted a visit from African-American playwright August Wilson, whose stage works loom large in the Bond era.

Before his arrival in Syracuse, the Toledo-born Bond had spent 11 years with the Oregon Shakespeare Festival in Ashland. Smaller but older than Ontario’s Stratford Festival, Ashland attracts select audiences, culture pilgrims, people who expect their classics to be reinterpreted. Like the Ontario fest, Ashland is not limited to works by the Bard. While there Bond directed one Shakespeare comedy, Twelfth Night, but he appears to have been the go-to man for works by African-American playwrights, such as Pearle Cleage’s Blues for an Alabama Sky, Suzan-Lori Parks’ Top Dog/Under Dog, Lorraine Hansberry’s Les Blancs, and several items by August Wilson, The Piano Lesson, Jitney and Ma Rainey’s Black Bottom, reprised as his first Wilson effort at Syracuse Stage (September 2008).

While in Ashland, Bond became personally acquainted with playwright Wilson, and then some. During a three-hour interview, Bond was usually intent, looking the listener squarely in the eyes, but he became his most sanguine and animated when speaking of shared time with August Wilson. Bond remembers being recognized and called to from a distance, and being welcomed with a bear hug. Later Wilson also conferred with Bond about plays he was writing, seeking a response with a hearty, colloquial, “Well, whattya think?”

The Ashland Festival might lie on the other side of the continent, but its influence on Syracuse has flooded in intermittently over the past six years. Sometimes we learned how different the two theaters were. A prime case was Bridget Carpenter’s Up (March 2009) about a day-dreamy loser who tied balloons to a Sears lawn chair in order to rise 16,000 feet into the air. The show was a hit in Ashland but was poorly received here by audiences and critics.

Imported from Ashland to direct Up was director Penny Metropulos, who has become a frequent visitor. She later helmed Steve Martin’s Picasso at the Lapin Agile (November 2009), Lisa Peterson’s An Iliad (May 2013) and John Logan’s Red (March 2012). An impassioned essay on creativity as seen in the life of modernist painter Mark Rothko, Red was one of the most admired plays of the last three years. Joseph Graves, who appeared in both Red and An Iliad, has worldwide connections but had also appeared in Ashland.

Influence from Oregon of a different kind came in the person of 39-year-old director Bill Fennelly, who was in charge of the effervescent production of A Midsummer Night’s Dream (March 2013), this year’s Syracuse New Times Syracuse Area Live Theater (SALT) winner and the most dazzling Shakespeare performance in the history of Syracuse Stage. As a co-production with the SU Drama Department, Dream gained mightily from the contributions of local faculty choreographer Anthony Salatino, not to mention the cream of the current drama students. For tricky, key roles Fennelly called on Ashland veterans William Langan as Duke Egeus and John Prybil as an uproarious Bottom. Fennelly enjoyed extensive Broadway and off-Broadway credits, but somehow it felt that his finesse and sense of adventure derived from his having been a directing fellow in Ashland.

The benign influences from the Oregon festival aside, Bond unmistakably had some bumps in his period of adjustment to audiences in moving from the comfy confines of an arts festival to the show-me demands of theatergoers in a Northeastern rust belt city. Not that Syracusans are hicks by any means. Even though Syracuse is the smallest and least affluent of the three upstate metro areas with regional theaters, the others being Albany’s Capital Repertory and Rochester’s GeVa (excluding Buffalo’s now-defunct Area Stage), audiences have long been the most sophisticated. No longer a “factory town,” Syracuse’s biggest employers are SU and the hospitals, which have drawn well-educated and well-traveled people to live here.

Some of the lowest points in Bond’s tenure came in the first season in which he controlled the agenda, 2008 to 2009. Things began well enough with Bond’s direction of Ma Rainey’s Black Bottom in September, but the run had just begun when gloomy events on the national scene affected everyone in the arts and the entire economy. Lehman Brothers collapsed Sept. 15, leading to a deep market plunge. Some of Bond’s most enticing plans with Cantor were put on hold.

Closer to home, the hiring of new assistant associate director Rajendra Ramoon Maharaj paid dreary dividends. In Maharaj’s conception for the John-Michael Teberak-Stephen Schwartz chestnut Godspell, slated for the December holiday slot, the Jesus (Anwar Robinson) of the Gospels had been transformed into a secular United Nations soldier in a sky blue beret. The familiar score (“Day by Day,” “Beautiful City”) had acquired an Afro-Caribbean beat.

Very few Syracuse Stage patrons are evangelical Christians, who likely found this Godspell blasphemous, but many people found the show’s greatest sin to be artistic. Worse, Bond himself had to step in to trim Maharaj’s sprawling length. It was the most poorly received holiday show since Robert Moss and Anthony Salatino launched the hugely beneficial collaboration with SU Drama in 1999.

This would also be the season of Bridget Carpenter’s regrettable Up, but before that Maharaj had more mischief to deliver. His casting of the Stephen Sondheim review Putting It Together (January 2009) featured some superlative voices, such as Chuck Cooper and Lillias White, but his handling of the singers offended more than Sondheim’s notoriously picky admirers. Instead of angst-ridden privileged New Yorkers, players came on like the cast of Married with Children in formal wear.

Two other productions, both happier occasions, would help to set the tone of the Bond era and also tell where his artistic heart lies. The first was Regina Taylor’s high-spirited Crowns (May 2009), based on a coffee-table book of photographs of the extravagant, high-rise hats Southern black women have long worn to church services. The slight plot resembled 5 Guys Named Moe with genders reversed. A skeptical youngster from the North learns to respect the exuberant music of the pre-civil rights South. Featured songs were actually quite well-remembered and easy to embrace by general audiences: “Wade in the Water,” “That’s All Right,” “His Eye is on the Sparrow,” and, inevitably, “When the Saints Go Marching In.”

Production values greatly enhanced Crowns’ appeal, beginning with Reggie Ray’s florid costumes, Felix E. Cochran’s scenic designs and Jennifer Setlow’s lighting. The transformative personality in the production was that of director-choreographer Patdro Harris, making the first of several appearances here. Among the first of Bond-favored directors, after Penny Metropulos, Harris brought an anthropologist’s knowledge of African-American and also African kinesthetics as well as a dazzling visual sense. He would later help Africanize McCraney’s The Brothers Size (April 2012), a play staged with grim realism elsewhere, and one of Bond’s signal achievements.

Crowns was the second production that season with a mostly black cast, after the previous September’s Ma Rainey. In all other respects the shows had nothing in common and represented entirely different theatrical experiences. It was a way of showing that if Tim Bond was going to produce works close to his own heritage, they would come with different faces and say different things. Ma Rainey, a landmark, is one of the most critically acclaimed dramas of the past 40 years, and is widely produced. Crowns is stylish light entertainment, much associated with Princeton’s McCarter Theater, managing director Jeffrey Woodward’s previous home base. While it is neither political nor threatening, neither is it patronizing nor overly sweet.

The Directors’ Chair

A producing artistic director should not be asked his personal tastes and priorities at the door. Arthur Storch, who came of age artistically in the 1930s, began and ended his time here with plays by Clifford Odets, Waiting for Lefty and Awake and Sing, as well as producing John Steinbeck’s Of Mice and Men twice. Robert Moss had been a professional associate of Edward Albee, and his Syracuse Stage tenure produced Three Tall Women and a revival of Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf?

Bond’s approach differs greatly from Syracuse Stage’s other African-American producing director, Tazewell Thompson, 1992 to 1996. Thompson never produced an August Wilson drama, the only one of four artistic CEOs not to. He also found it difficult to connect with audience tastes, especially with African-American projects. The exception was the return appearance of Thompson’s own Constant Star (October 2004), an upbeat celebration of the life of crusading journalist Ida B. Wells. It wowed audiences and won a SALT Award.

What the two men have in common is a flair for opera. After leaving Syracuse, Thompson directed in two dozen of the world’s leading opera houses, including Milan’s La Scala, and helmed a Porgy and Bess on PBS that was nominated for an Emmy Award. Timothy Bond’s experience with opera has been post-modern. He was assistant director to Peter Sellars for the world premiere of John Adams’ Death of Klinghoffer at the Brooklyn Academy of Music, repeated in Vienna and Brussels.

Earlier in the spring of Crowns came a production that more emphatically contrasts Bond’s tastes and talents with those of the other three men who have held his position. When he announced a revival of The Diary of Anne Frank (April 2009), more than a few subscribers groaned that the drama of the Dutch girl’s confinement has long since worn out its welcome through overproduction. In scheduling, however, Bond took heed of the rancorous controversy over tempering with Anne Frank’s legacy and the displeasure that many Jewish intellectuals, most prominently Cynthia Ozick, had with Frances Goodrich and Albert Hackett’s 1955 stage drama. The complaint was that Goodrich and Hackett, who also worked with Frank Capra on It’s a Wonderful Life, had both sweetened the story and made it more ethnically generic rather than specifically Jewish.

To take a new direction, Bond used the revised text by Wendy Kesselman. Startling differences emerged immediately. The Franks and the others are forced to wear the sewn-on yellow star. Anne (Arielle Lever), far from being a saint, asserts her emerging sexuality and resents her mother. Her sometimes abrasive hoydenish antics grate on the patience of the other residents, and we’re inclined to sympathize with them. A signature of Bond’s direction is that listeners must be as expressive as speakers, and their response boosts tension. More than in any other production, we feel how claustrophobic that hiding place was.

The most striking departures in the production were director Bond’s call, rather than emphases from Kesselman’s text. When we get to Anne’s famous lines about hope, the most quoted of all her words, they are in voiceover: “I believe, in spite of everything, that people are truly good at heart.” The thunder of jackboots on the stairs nearly drowns her out, and we have to struggle to hear her.

Following this, Bond has Anne’s father Otto Frank (Joel Leffert) spell out in tears what happened to the denizens of the hidden room. The Holocaust is, of course, already one of the best remembered events in World War II, but a live speaker enables audiences to sense the horror in a way that a statistic or black-and-white photograph might not: the extinction of the flawed people whose time we have just shared.

From reports Bond was deeply empathetic to Leffert’s performance, and when speaking of the rehearsals nearly five years later at a table in Phoebe’s, emotion still flushes his voice. The Goodrich-Hackett Anne Frank is a worthy high school literature assignment encouraging students to accept tolerance. The Kesselman-Bond Anne Frank matched the director’s highest criterion for the theater as articulated in his 2007 Syracuse New Times interview: to provoke dialogue about our place in the world.

Two patterns in presentation flow from the Anne Frank model. One is that very familiar works, especially when they look like comfort food for audiences, will be re-imagined and treated as if they are startling and new. Among these are William Gibson’s The Miracle Worker, directed by Paul Barnes (March 2011); Irving Berlin’s White Christmas, directed by Barnes and choreographed by David Wanstreet (December 2012); and, most arresting of all, A Christmas Carol, directed by Peter Amster (December 2013).

As for shows that provoke dialogue about our place in the world, such might be said about many popular productions that could be seen in almost any regional theater because they’re proven good box office, such as Jonathan Larson’s rock opera Rent (January 2011), directed by Salatino, or John Logan’s Red (March 2012). More pertinent to Bond’s ideal was the production of Nilaja Sun’s No Child. . . (September 2010), with Bond himself directing, about the struggles of an idealistic drama teacher (Reenah L. Golden) in a hardscrabble inner-city school. By staging a play about convict settlers in early Australia, the dregs of the Empire, she transformed the lives of her desperate students. Despite the importance Bond placed on No Child . . . , he knew it would never have the appeal of Rent or Red, and so it was staged before the regular season began in the smaller, remodeled Storch Theatre.

Other selections supporting Bond’s ideal would include Tom Griffin’s comedy about a group home, The Boys Next Door (October 2011), directed by Bond, and David Lindsay-Abaire’s class-conscious comedy-drama Good People (March 2013), directed by Laura Kepley. Less successfully, seeking dialogue about our place in the world also brought us two Ping Chong premieres: Tales from the Salt City (October 2008) and Cry for Peace: Voices from the Congo (September 2012). Both works employed original voices, but they suffered from the compiler’s lockstep, one-size-fits-all dramaturgy.

Pitt Stop

The culmination of Timothy Bond’s tastes and artistic ideals is, of course, his commitment to stage all 10 of August Wilson’s Century Cycle of dramas. Nine of them, excluding Ma Rainey’s Black Bottom, are set in Pittsburgh’s Hill District, the most prominent black neighborhood, one for each decade of the 20th century. The plays were written out of chronological order between 1985 and Wilson’s death in 2005, and all of them stand well on their own. Despite the preponderance of local references, Wilson is never parochial, always seeking the universal in the particular. The focus is on black history, with recurring characters and themes, with touches of magic realism, but it’s a world white audiences may enter and immediately orient themselves. Past racial injustice may come up (how could it not?), but playgoers do not suffer finger-pointing for the past sins of the majority culture.

Wilson’s critical reputation, including two Pulitzer Prizes, is secure and does not need a boost from Syracuse; several other cities have already staged all 10 plays, with Seattle, Boston, Pittsburgh and Rochester’s GeVa placing them in chronological order. Few American dramatists have given us 10 plays that ticket-buyers would still want to see in toto. Certainly not Eugene O’Neill and probably not the mid-century giants Arthur Miller and Tennessee Williams. Wilson’s important contemporaries, Sam Shepard and David Mamet, have been in decline recently. For quality alone, Bond is making a strong case with Wilson, if not greater than the others, then more consistent.

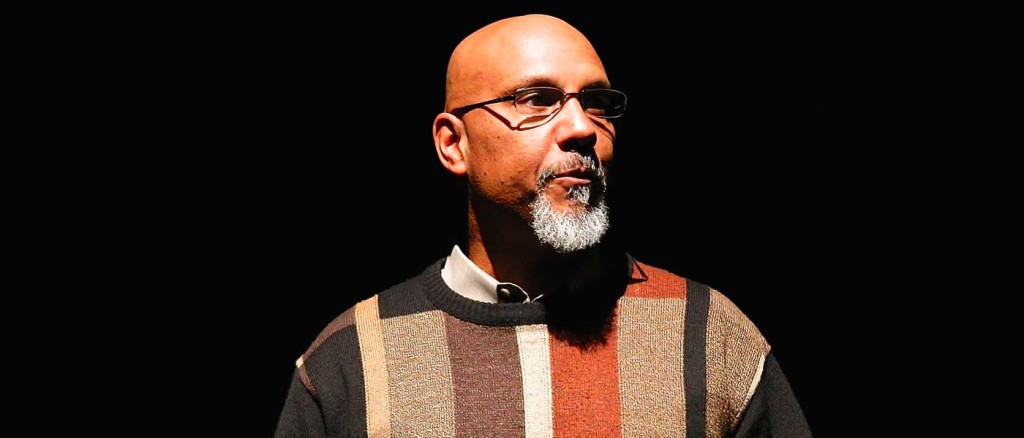

When Bond is asked why he has the commitment to Wilson he cites the personal connection, the shared conversations, the assurances of trust, especially as experienced in Ashland. It is also unmistakable that the director brings an authority over the different rhythms of urban speech and the demotic poetry. Even though Bond is the son of a college president and a graduate of Howard University, he knows the angst and the gaiety of characters at every social level. Director Bond has a light touch for the characteristic wise fools in Wilson plays, who are often quite funny but can babble so that many other characters dismiss them, until we know they’re speaking deep truths. But the director can also endow tragic figures, such as Troy Maxson in Fences, with resonant moral weight.

Bond has presented four Wilsons in his time here. Ma Rainey’s Black Bottom (September 2008), reprised from Ashland, bristles with the razzle-dazzle of a rules-breaking young playwright. We have to learn that we care not so much about the fabled jazz singer of the title but rather the forgotten musicians, seen on a lower stage, who backed her up. Radio Golf (February 2011), set in the 1990s, is often ranked lower among the 10 because the themes of affluence and gentrification were new to the playwright’s world, and also because he was literally on his deathbed when he was trying to finish it. Nonetheless, Tony-winning actor Thomas Jefferson Byrd gave an electrifying performance, with as brilliant a monologue as can be found in any of these four. Two Trains Running (February 2013), set near the time of the Malcolm X and Martin Luther King assassinations, was a drama rich in intellectual and political conflict. Actor G. Valmont Thomas, yet another Ashland alumnus, soared to the heights.

Which leads to Fences (May 2010), often cited as the top of the 10 plays. In reviving it Bond was inviting comparison to the March 1991 Syracuse Stage production, led by director Claude Purdy, a close friend of Wilson’s and usually thought to be one of his prime interpreters. That might have been two decades earlier, but some of us took notes and have refreshed our memories. The Purdy version suffered from projection problems, with many players speaking in heavy street accents that could not be discerned 10 rows into the audience. Purdy’s Troy, the distinguished stage actor John Henry Redwood, played the garbage man as a wounded giant.

With James A. Williams as Troy, Bond’s version shook off the legacy of mellifluous James Earl Jones to give us a hero of low social station but raging with imposing strength. Like so many great dramas, Fences is a family story, spelled out in Troy’s wrenching conflicts with his wife (Kim Staunton) and sons (José A. Rufino and Stephen Tyrone Williams). Bond’s Fences was not only more powerful than Purdy’s, it is his peak moment as a director in the last six-and-a-half years.

At age 55 Timothy Bond is now at home in Syracuse. When asked what he has learned about what local audiences really like, he smiles and itemizes a short list. For last fall’s productions, Blithe Spirit, Scorched and A Christmas Carol, he scored a bull’s eye each time. And subscriptions are up for the spring.

For more like ‘Bond’s Market’ – click here for STAGE