Tom began to head home from the party after 2 a.m. that morning. A farmer, who did odd jobs for neighbors and who loved to play the fiddle, he lived in the Hollow with his wife, Sadie and their four young boys. Earlier in the evening, he had entertained women as they quilted and men who worked on finishing a favorite alcoholic drink of the time called applejack. Tom’s path down the hill must have been as familiar to him as his set list, which, according to sources, consisted of just two tunes, the English/American “Heye Betty Martin” and the well-known anti-Irish satire, “Brian O’Linn.”

It was just springtime in the early 1810s, and he wore his usual homespun pants with a deerskin belt and a patched white shirt. Since the snow had mostly melted, his feet were probably bare. Only during the cold winter months (say February — to the Onondaga, Ka-na-ho-ta, or “winter leaves fall”) did he wear moccasins.

He was well on his way toward home when he heard the foliage crack behind him. Someone was there, he may have thought. But when he peered into the darkness, the only eyes he saw staring back were those of a large wolf. Deep in the animal’s element, all appeared to be lost for Tom. He had eaten and drank at the party as well, and was in no condition to race.

Then, a second wolf appeared. When the beasts gave chase, he fled but to flee, but, to his surprise, he noticed a shanty ahead which he had helped a shingle weaver build about two years prior. Leaping into the building through a small trapdoor, he scrambled up the peg-pole and cut the cord — closing the door, and the first wolf in, too. Fiddle in tow, he held tightly to the rafter while the wolf paced below and waited.

According to a source, he played a tune to his captive audience. Soon it was morning, and the search party that Sadie had organized heard his cries. When they learned what was inside, a few of the men stuck their rifles between the logs and fired.

A few weeks later, Tom answered his door and found three of the men outside his cabin. handing him a deerskin bag, one said

“Here’s somepin’ to keep you warm next winter when you start rememberin’ that cold night up in the shanty,” he said.

Photo provided

Tom opened the bag and pulled out the fine wolfskin wrapped inside.

“I do, thank you,” he replied. “I know you all want me t’have this, but I can’t take it. That wolf was only hungry. ‘T’would be unchristian t’ glory over him losin’ a meal.”

He accepted the $50 bounty on the wolfskin offered by the men, but only if they invited him to play at upcoming social gatherings free of charge. It appears from this story that Tom was a well-respected man in Onondaga, and it isn’t strange to see why, except that Tom was black.

This story was included in the book, The Hill and the Hollow, by local historian Marian K. Schmitz, and is well worth the read. It got me wondering what life was like for African-Americans around the time that Syracuse was beginning to form. What did Tom’s color have to do with the way things panned out, if anything? How much of a threat did wolves pose to settlers in early Onondaga County? Why was it Tim who provided the entertainment that night? The trek from Onondaga Hill to Onondaga Hollow (now, the Valley), seems like a stretch to us now, but what was their relationship before Syracuse eclipsed them as “civilized” parts? The answers I found surprised me.

Smoke from the Revolutionary war had barely cleared when the former soldier and future trader Ephraim Webster left his family’s farm in New Hampshire to go west in 1784. He lived with the Oneidas for two years, dealing in furs and supplies while at the same time learning Native language and customs. The Onondagas introduced him to the valuable salt springs, and he was invited to set up a trading post by the chiefs.

With their permission, he soon settled in an area which would become known as the Hollow. Other folks, hearing about the opportunity, came too. By 1798, when the town was incorporated, approximately 80 people had come to the area, mostly from New England, leaving behind high taxes and land as scarce land.

Some made their homes in the Hollow, but many others preferred the high ground of the Hill. After a few wealthy “founders” bought land from a state sale and sold small lots, a town began to form.

Competition to host the county seat pit the Hill against the Hollow. Those partial to the latter argued that its location was easily accessible to travelers and that it was home to many of the most prestigious and wealthy townspeople, including Webster. Still, the Hill country had ample land to improve. The swampy land to the east which later became the site of Syracuse seethed with rattlesnakes and bears and was out of the question. (Bear and Wolf streets were practical names it turns out). By 1810, the Hill had seven pubs and eight stores, and it retained its place as county seat until 1827 when the coming of the Erie Canal inspired its move to Syracuse.

Any town worth its salt needs to have a newspaper. The Lynx was founded in 1811 and preceded even the Onondaga Register, which is often cited as the first local rag. Thurlow Weed, the well-known editor and Whig political booster (he backed Seward over Lincoln!) got his start here. The paper’s founder, Thomas Crittenden Fay, wrote in the paper’s prospectus,

“I shall endeavor to promote the nation’s interest, with the industry of the BEAVER while I watch its enemies with the eyes of a LYNX.”

But it was wolves that caused the real alarm. Since the community was carved out of the wilderness, the majority of government business involved dealing with plants and animals, according to minutes of town meetings in 1810. Everyone was responsible for removing Canada thistle and Tory weeds from their properties and roads, and people who let their animals roam during the winter months were charged a $5 fine, the same as for failing to eradicate the monarchical plants.

Wolves had been used for feasting mainly on wild deer herds until settlers began to erect fences around their livestock, which, of course, was to the wolves’ advantage. In colonial New England, wolf heads had basically been a form of currency due to the bounty prices. This became problematic when hunters sometimes handed in the same head twice for payment — one solution to this was to cut off the ears of captured animals and bury them separately.

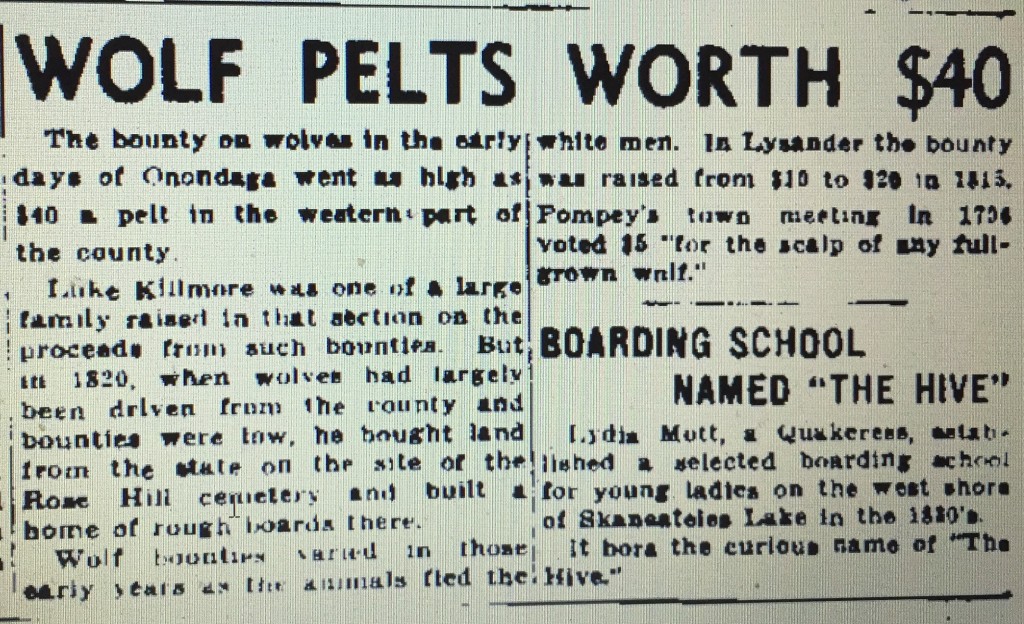

As Tom’s story shows, people felt threatened as well. Despite the gruesome due diligence involved in the bounties, the bodies of wolves were not necessarily wasted. In unheated colonial town meeting houses, wolfskin bags were attached to seats that could be used as leg-warmers. Thus, the bounty that would later be offered in Tom’s story was not unique; its amount would fluctuate as the wolf population did.

In addition to the growing marketplace in town, agriculture required the bulk of the labor, and even to abolitionist Central New York, some settlers brought slaves. Of the northern states, New York had the largest number of slaves, but also of free blacks. After Independence, the national map of bondage we are familiar with came into being on the territory. Northern states began to outlaw slavery. In 1785 the New York legislature divided over how many rights blacks would be granted as citizens. Intermarriage, the right to act as a witness in court and the right to hold office were agreed upon, but the two houses deadlocked on whether black citizens could vote. It was only 15 years later, in 1799, that slaves were gradually emancipated: boys born after July 4 would be freed no later than their 28th birthday and girls their 25th. One of the first generations of black Americans in New York would spend their “formative” (and most lucrative) years in slavery.

As Edgar J. McManus reminds us in his book, Black Bondage in the North, “some runaways fled to the forest where they sought refuge among the Indians.” The Iroquois were crucial agents in the safe harbor and passage of runaways, especially in the colonial era. McManus points out that “recovery clauses” included in tribal treaties. Rewards for the return of slaves were offered, but, “even Indians as closely allied with the English as the Iroquois refused to return blacks who took refuge among them.”

The Jerry Rescue story, in which an escaped slave was broken out of jail by Syracuse abolitionists, is now well known. However, well before the tumultuous 1850s,“Central New York was a magnet for African-Americans, whether in Rochester, Buffalo or Syracuse,” Doug Egerton, a history professor at Le Moyne College told me. “Many of those new to the area were from Massachusetts, and their strong religious faith led them to oppose slavery.”

A few notables such as Samuel Day, the first Onondaga County judge, emancipated their slaves upon arrival here. Another story has it that John Ellis, who owned 6,000 acres on the Hill, requested in his will to be buried with the slaves he had bought from Virginia. However, his wife freed them after he died, so Ellis’ wishes were probably left unfulfilled. In addition to the manumission of slaves, some undoubtedly escaped to Canada. A young woman named Harriet, described as, “so fair that she would generally be taken for white,” stayed with her owner, a Mississippian named Mr. Davenport at the Syracuse House in 1839. A black waiter named Tom Leonard arranged for her to be smuggled out of Syracuse to Marcellus, Skaneateles and on to Peterboro where the abolitionist Gerrit Smith arranged for her journey to Canada.

Apparently Tom (no relation to the waiter) had come from “down south way” in 1808, but when asked about his past, he replied simply that he had “jumped over the broomstick,” a wedding custom thought to be practiced by slaves. had he meant he jumped over the whip? It seemed that the townspeople had their views.

“No one who knew Tom ever questioned his origin — no one that is, who valued his own standing in the community or the good opinion of his friends and neighbors,” Schmitz writes.

Whether they were escaped slaves, free blacks or, somewhere in between, like Tom, Central New York granted more freedoms to black Americans than many other localities did.

However, I began this story wondering how much freedom one could have in the wilderness without proper protection from our version of lions, tigers and bears. In colonial New York, free blacks were forbidden to carry firearms. If Tom had been carrying a rifle along with his fiddle, we might have been spared a Fenimore Cooper story, but Tom could have gone home to his wife, kids and neighbors without risking such a run-in out in the woods that night.

Douglas Egerton, whose 2009 book, Death or Liberty: African Americans and Revolutionary America explores these contradictions by focusing on how black Americans saw slavery in the Revolutionary era. He pointed out that local or state law did not prohibit free men from carrying guns, be they white or black.

“If you were a bad guy, then it was possible that the sheriff would disarm you, but it was not color that decided the question.”

This was unexpected, but good to hear. It makes sense: the less black Americans in a population there were, the less necessary it became to legislate them into a coffle. In a way, Tom’s meeting with the wolf was much simpler than I had imagined before the research.

Yet much remains unknown about the context of the incident. Canada thistle and Tory weeds? We thought liberty cabbage and freedom fries were bad…

More seriously, why did Tom only play two songs on the fiddle — “Heye Betty Martin” had English roots but was played and sung by black musicians as well. “Brian O’Linn” was about a lovable but savage Irishman. Isn’t it likely he knew other songs, just “not safe for work?” Maybe it depends on who, if anyone, taught him to play.

He was also a young man around 1810, so it’s fitting that he played the fiddle. Very common in early America, it was often handed down from father to son at a fairly young age. It was also considered “slightly servile” and a large percentage of the musicians who played at socials and dances were black. For such a contentious instrument, outsourcing immorality may have been a compromise that was easy and pleasurable to make for all involved.

Where did Tom and his wife come from and where did they go? They seem to have made a comfortable home in Onondaga County. Still, as westward expansion continued, the debate over slavery intensified. In the book and film Twelve Years a Slave, Solomon Northrup, also a farmer and violinist, recounts how he was kidnapped from eastern New York in 1841 and sold to a planter in New Orleans.

Commenting on the Missouri Compromise in 1820, shortly before his death, President Thomas Jefferson wrote,

“But as it is, we have the wolf by the ear, and we can neither hold him, nor safely let him go. Justice is in one scale, and self-preservation in the other.”

For a man who is remembered as such a principled and uncompromising idealist, this comment is deeply disappointing. Tom no doubt desired a secure life as well. As he looked at the wolf’s body on the shanty floor, he remarked, “Poor ole feller. Had his heart set on a tasty meal – namely me.”