Twenty years ago on Central Issues, the WCNY-Channel 24 public affairs program, host Dan Cummings asked Lee Plavoukos, then associate counsel to the speaker of the New York State Assembly, if we should have a constitutional convention. A provision in the New York state constitution mandates that every 20 years citizens decide whether they wish to convene a convention to revise and amend that document.

Plavoukos described the endeavor as romantic. “It’s a great idea,” he told Cummings then, “but it’s not worth the risks.” Today he thinks we have no other choice.

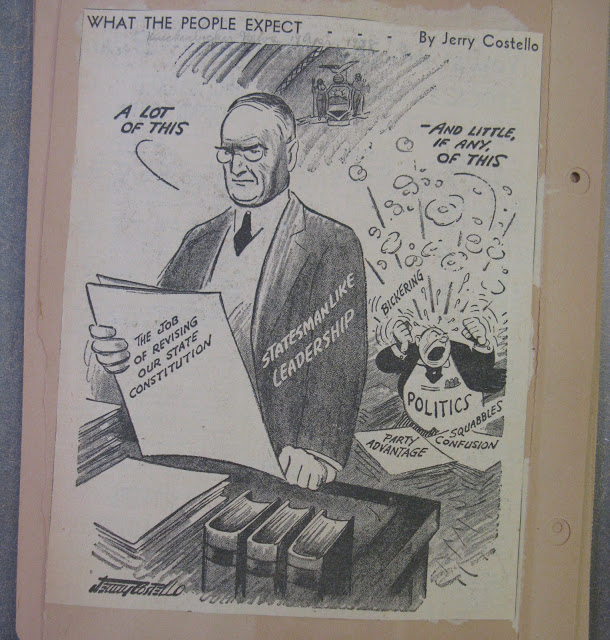

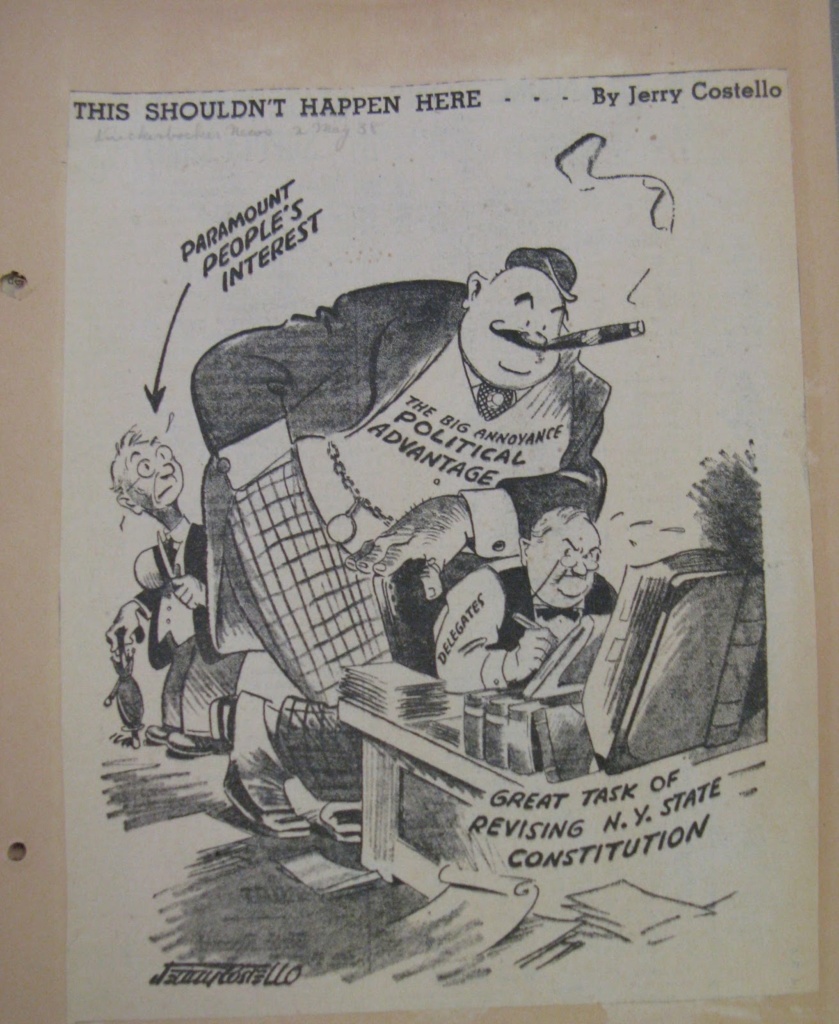

In a telephone interview, state Sen. John DeFrancisco, currently touring to determine the prospects for a gubernatorial campaign, dismissed the concept as having “very little likelihood of success.” He noted that good government groups may see a constitutional convention as the only way to deal with current corruption in Albany, with the election of three delegates from each state Senate district together with 15 statewide delegates bringing fresh faces into the political system. “But realistically,” he observes, “who are the people most likely to get elected?”

Former City Hall lawyer Joseph Bergh, whose practice often included constitutional issues, views the convention as an opportunity to address such issues as municipal finance and the improvement of the court system. He agrees with Plavoukos that it could provide a platform for settling the issue of consolidation of government services.

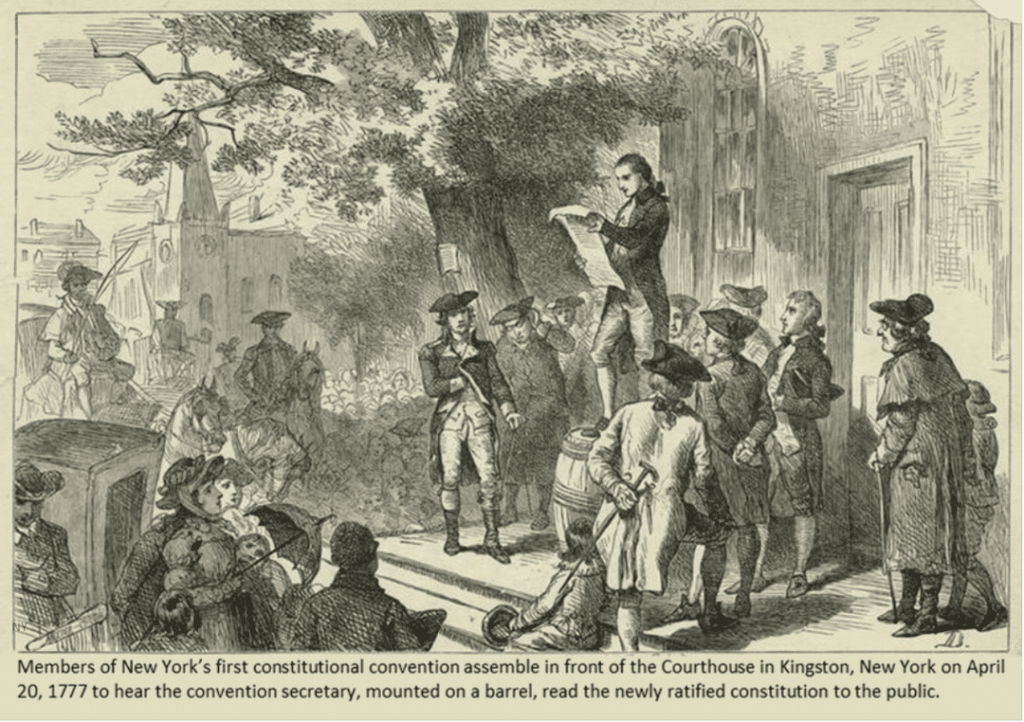

“The last time we had a constitutional convention,” he points out, “the world was a lot different.” That time, which Plavoukos describes as a distant mirror of today, was

That year the voters approved the convention, 1,413,604 to 1,190,275. But civic attitude toward the process can be gauged by the total vote on the proposition, which was 3 million less than that cast on the governor’s race on the same ballot. Voters rejected the concept in 1957, 1977 and 1997.

That year, despite controlling the governor’s office, the state Senate and New York City, Democrats failed to win control of the convention. The final tally was 92 Republicans, 75 Democrats and one member of the American Labor Party. A special convention was called by the state Legislature in 1967.

The 1938 version attracted an all-star lineup of then-prominent politicos. Frederick Crane, chief judge of the Court of Appeals, was elected convention president. Also on hand were four-time governor Al Smith, Sen. Robert Wagner, Congressman Hamilton Fish and urban planner and power broker Robert Moses.

During a five-month session, the delegates debated and enacted proposals both progressive and traditional. Conflict over an “exclusionary rule,” prohibiting the use of any evidence obtained by an illegal search or seizure, previewed that year’s race for governor. Thomas Dewey’s arguments against the rule prevailed, but Herbert Lehman beat him that November.

If voters approve a convention for next year, they may be providing a stage for a confrontation between environmentalists and developers over the future of Adirondack Park. Unions fear their right to organize, to receive the prevailing rate on construction projects and to bargain collectively might be adversely affected courtesy of powerful special interests.

And then there are the strange bedfellows. Advocates for Planned Parenthood and the National Right to Life Committee finally agree on one thing: Both groups oppose the constitutional convention. The New York State Conservative Party and major public employee unions view the prospect of a constitutional convention as a dangerous waste of time and money.

The New York State Teachers Union is warning members and the general public that the current education system would be compromised by private school tuition vouchers, tax credits and charter schools, all made possible courtesy of the constitutional convention.

There is, however, one issue that everyone concerned can agree on: Albany has a longstanding tradition of government corruption. “After I left Albany,” Plavoukos recalls, “I realized that politics is all the organized crime we can agree on.” Since 2000, almost three dozen members of the state Legislature have faced criminal charges resulting in their resignation or removal. Several good government groups view the convention as an opportunity to address the issue of ethics reform.

The convention could create a full-time legislature, with term limits and a ban on any outside income. Also possible is establishing the right of every New Yorker to health care, including reproductive rights protections. Currently, the state constitution is silent on those issues.

“Right now we see the far right and left pulling the political spectrum so far apart there is no longer any common ground for compromise,” Plavoukos projects. “Each side points fingers at each other as to the reason why nothing is getting done. Call it institutionalized failure. A constitutional convention could provide the vehicle to bring policymakers back to the middle, long enough to do something positive, with the rest of us looking over their shoulder.” SNT