As an increasing number of states ease up on the once illegal use of marijuana, it is apropos to note that it was 80 years ago this month that the great experiment to make alcohol illegal, Prohibition, was finally declared a failure.

The topic of Prohibition is explored, with a local twist, in The Culture of the Cocktail Hour, a new exhibit at the Onondaga Historical Association. The show accompanies, and provides perspective for, a larger exhibition, Fashion after Five, which features 22 cocktail dresses drawn from the holdings of the association and Syracuse University’s Sue Ann Genet costume collection. Arranged on realistic mannequins, the gowns date from the 1920s through the 1990s.

Prohibition of alcohol had become federal law in 1920 with the adoption of the 18th Amendment to the Constitution.

But instead of raising the morality of the nation, as its advocates had long argued it would, it increased lawlessness. This ranged from the violent activities of gangsters like Chicago’s Al Capone to everyday, formerly law-abiding citizens who were technically breaking the law if they consumed a single beer in the backroom of a neighborhood club.

Liquor had been deeply woven into American social life since earliest colonial days. In the 17th and 18th centuries, beer and hard cider were considered safer drinks than water drawn from unknown sources. Wine was regarded as a basic food. Some of Onondaga County’s earliest settlements included a tavern from their beginnings.

By the mid-1800s, however, some people believed that the consumption of beer, whiskey, rum and other intoxicants had become much too widespread. They argued that it created hardships for families, especially for women and their children as husbands drank away wages. Taverns bred gambling, vice and prostitution, they cried.

This “Temperance Movement” coincided with the mid-19th century’s great religious and moral revival–the same revival that created the anti-slavery and women’s rights movements–and it persisted, right into the early 20th century

American cities like Syracuse, teaming with new immigrants, had grown into large urban centers. Their saloons and breweries became symbols to some citizens, usually those living in rural America, of a growing moral decay in the nation. At a local level, temperance advocates began to lobby many towns and smaller cities to adopt “dry” laws, banning liquor within their borders. By 1916, 10 of Onondaga County’s 19 towns had such laws.

The Temperance Movement eventually achieved its goal with passage of the 18th Amendment: The National Prohibition Act essentially turned the entire United States dry. It was ratified in January 1919 and took effect a year later, making the production and consumption of virtually all liquor illegal.

Enforcing the law, however, proved almost impossible. Most Americans, in little ways, clever ways and, sometimes, violent ways often got around the ban. There was illegal smuggling from Canada, concealed stills in the countryside, secret hiding places in homes and the wayward, but always popular, speakeasy.

Speakeasies sprung up all over Syracuse, from small backroom operations in homes to elaborately decorated upper floors in the heart of downtown. These classier speakeasies would evolve into the nightclubs of the 1930s and 1940s, after the end of Prohibition in 1933.

Ironically, women had achieved the right to vote in 1920, with the passage of the 19th Amendment. The decade of the 1920s became one of their liberation, perhaps most notably in dress, with the image of the “flapper girl” in her short hair and ankle-revealing skirts.

But the anonymity of the speakeasy also supported another facet of this liberating decade for women. Somehow, women seemed more at ease drinking in a hidden speakeasy, instead of publicly, in the old male-dominated saloon. Plus, the speakeasy needed their business and did not discourage women drinkers. For the male customers, the already naughty nature of a speakeasy was only enhanced by the presence of women.

And the cocktail thrived. New recipes became popular, such as the daiquiri, to help flavor the sometimes watered-down or poorly distilled liquor that might arrive at a speakeasy. Also, the flavored cocktail was often preferred by the increasing numbers of women customers frequenting the speakeasy.

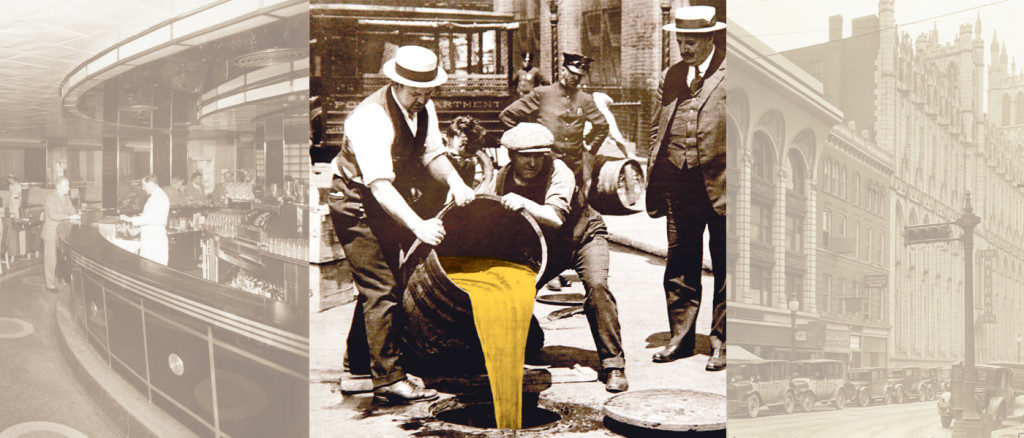

Local, state and national law enforcement agencies were supposed to stop all this illegal alcoholic consumption and production but never really succeeded. There were raids, arrests, bottles smashed and gallons of liquor dumped into sewers. But the illegal activity soon returned, because the public demand was always present and there was money to be made.

The intensity of police and judicial activity varied greatly. Some officials were lax, perhaps questioning the wisdom of Prohibition. Undoubtedly, a few were bribed to look the other way. But several pursued their job with great energy, such as when federal agent Charles Kress was assigned to Syracuse. A federal agent detailed here in the late 1920s, Kress was the “Elliott Ness” of Syracuse, feared by bootleggers for his aggressive raids and sometimes flamboyant stunts in breaking into speakeasies. Syracuse was not Chicago, however, and there was little open violence.

Syracuse police, Onondaga County sheriff’s deputies and federal agents made many arrests, but some were dismissed on technicalities. Even if bootleggers were found guilty, penalties were not severe. A common dodge for speakeasy operators might be lack of a search warrant by the raiders. And the speakeasy management was adept at quickly hiding or disposing of the incriminating liquor evidence.

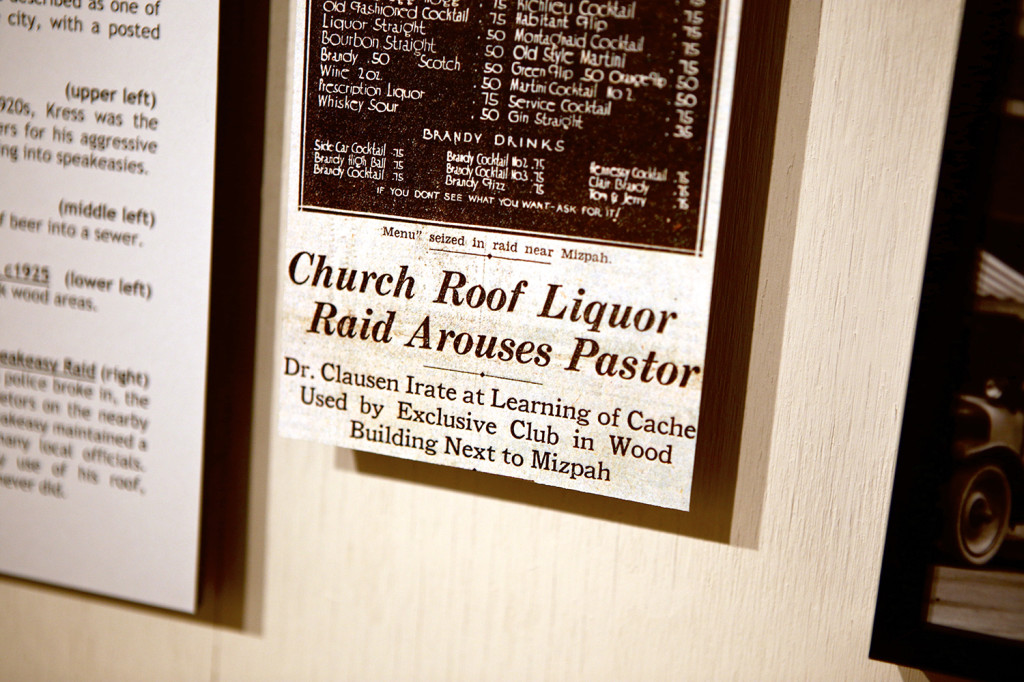

Speakeasy raids made good headlines, though, and one of the most notorious in the Salt City occurred on Feb. 7, 1931, when Syracuse police broke into one particularly elaborate hideout just off Columbus Circle. It was described as one of the most lavish speakeasies ever found in the city, with a posted menu listing 75 drinks and cocktails. This most ornate speakeasy was on the third floor of the Wood Building, in the 200 block of East Jefferson Street.

Working on a tip that “many young girls of the city, some unescorted” were seen frequenting the building, Syracuse Police detective Martin Kavanaugh walked over from police headquarters near Clinton Square and rang a bell next to a locked door leading to the upper floors.

A man, later identified as Arthur Anklin, opened a peephole in the door and announced, “Sorry gentlemen, but only members are admitted here.” Seeing a glass transom above the door, Kavanaugh broke the glass, crawled through and unlocked a heavy metal door to let five other officers enter. Meanwhile, Anklin had run up to his speakeasy and was doing his best to dispose of all the liquor.

When Kavanaugh and the other officers reached the third floor, the local press reported, they were “amazed at the scene which met their eyes.” The décor was fancier than some of the high-class lounges in existence before Prohibition. There was a long mahogany bar in front of a large mirror, cozily furnished chairs, plush oriental rugs and softly shaded floor lamps, with private rooms off the main lounge. If there was any doubt about its function, the prominent display of the menu of drinks and cocktails erased that uncertainty.

While keeping an eye on Anklin, who had grabbed his coat and hat, the police began a search for any incriminating booze. A few quarts of whiskey and several bottles of Canadian ale were uncovered, but the largest quantity was noticed lying in the snow on a nearby lower roof of the adjacent First Baptist Church and Mizpah Hotel. It had clearly been quickly tossed out a window. Anklin was arrested.

The police also confiscated a list of the private club’s “members,” which reportedly included prominent local citizens. The case gained a great deal of attention because the speakeasy had been operating adjacent to a Baptist church and because the roof on which the liquor had been thrown was just outside the study of its pastor, the Rev. Bernard C. Clausen.

Clausen was infuriated that such illegal goings-on had occurred in the shadow of his sanctuary. The minister, upset by the emergency use of his roof, demanded that police release the names of the club’s members. This must have given several of the speakeasy’s regulars a case of the sweats. But they were not to worry. Because Kavanaugh did not have a search warrant, the raid was ruled illegal by U.S Commissioner Edward Chapman. Anklin was freed.

The Wood Building speakeasy soon reopened, but its manager did not reckon on the fury of Clausen, who began a crusade against the place. Continuing attention by the press, generated in part by Clausen, eventually forced Mayor Rollie Marvin to exert pressure on the building owner to evict Anklin and his “private club.” Anklin left, and it was assumed he moved his operation to some other, undisclosed location.

The Wood Building still stands, along with its neighbor, the former First Baptist Church and Mizpah Tower. While the latter is well known for its landmark status and long-standing odyssey in search of a successful re-use, the Building remains fairly anonymous – perhaps as Anklin would have wished it to be in 1931.

A visit to the Onondaga Historical Association’s exhibits offers more colorful history of the cocktail in Syracuse along with a chance to view styles of cocktail gowns over the years, including designs that might have once graced Syracuse’s most notorious speakeasy.

Dennis Connors is curator of history at the Onondaga Historical Association.