Thirty-five years ago this week, a little-known cleric in a country few of us had heard of, sent a letter to the president of the United States. On Feb. 17, 1980, Archbishop Oscar Romero called on President Jimmy Carter to stop sending weapons to his country, arguing that to do so would only bring more repression to his long-suffering people.

Romero’s words turned painfully prophetic little more than a month later, when he himself was gunned down at the altar while saying Mass in a hospital chapel.

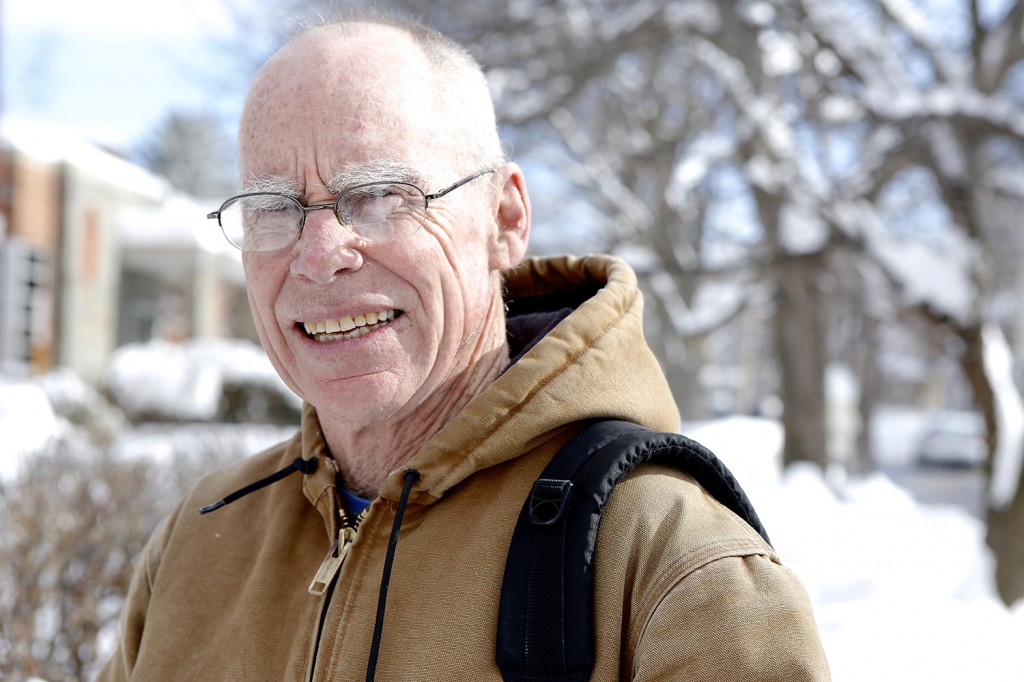

A day earlier, as the once-timid Romero delivered what was to be his final sermon, Kip Hargrave was one of the millions in El Salvador who tuned in to the broadcast. As the archbishop calmly spoke against the injustice in his country, the former Marine turned missionary, who now resides on Scott Avenue in Syracuse, listened intently.

As was his weekly custom, the archbishop named case after case of people who had disappeared or been murdered by the armed forces or the death squads allied with them. At the end, Romero called out to the army, begging the soldiers to stop killing their own countrymen and women, obeying their conscience even if they had to defy a direct order. It was as if he had crossed a line – many felt that he had signed his own death warrant.

Hours after the archbishop’s killing, Hargrave found himself amid a crowd of thousands carrying Romero’s body through the streets of San Salvador to the National Cathedral. For the next five days, almost by accident, Kip Hargrave had a front-row seat at some of the most dramatic moments leading up to El Salvador’s civil war.

Between Romero’s murder and his burial a week later, Hargrave, by virtue of his nationality and his position as a Maryknoll seminarian, was pressed into service to assist in keeping order as hundreds of thousands came through the Cathedral to pay their respects. He barely slept, finding ways to be of service as a grief-struck populace struggled to honor their fallen leader and at the same time advance his legacy.

The week ended as it began, with tragic violence. At the archbishop’s funeral, soldiers opened fire, panicking the crowd, and dozens of people died, most of them crushed against the Cathedral’s iron gates as they fled the gunfire.

Hargrave had taken a roundabout route to El Salvador. A graduate of Notre Dame, he had served in the Marines, was shot down in Vietnam and spent a year in rehabilitation. For a time he ran a paving business in his hometown of Evansville, Ind., before deciding that he wanted to be a Maryknoll missionary priest. “I was in the seminary and they sent me to El Salvador as part of my training,” he recalls That was in 1979, and Central America was already in the throes of revolution.

Now retired after a long career working with Catholic Charities settling refugees in Central New York, Hargrave reflects on the legacy of Romero, who is now being considered for sainthood by the Catholic Church’s first Latin American pope.

Michael Davis Photo | Syracuse New Times

“He did what great leaders do,” says Hargrave. “Had he not spoken up back then, nobody would have ever known what was going on. Because he did what he did, so many others were able to speak up. It just means so much to me that somebody at that level was willing to give his life like that. “

Last month the Vatican announced that the process of Romero’s beatification, which had been put in a deep freeze by previous popes, had been “unblocked.” Pope Francis said that he believed that Romero’s murder was committed out of “hatred of the faith,” a hint that his beatification process might move along quickly.

“It says a lot about Pope Francis,” says Hargrave. “He is a Latin American, and thinks like a Latin American. He was always clearly of the church. Francis just sound like a good Latin American cleric. He reminds me so much of Romero — that same sense of humor.”

He remembers one of Bishop Romero’s most enduring teachings. “He said he would rise again in the Salvadoran people, but it’s also in a lot of other people that he’s alive.”

Hargrave is one of those people. This week he boards a plane for Nicaragua, where he and a group of parishioners from St. Lucy’s Church will be working with a rural community in central Nicaragua that Syracusans have been helping for 20 years.

Ed Griffin-Nolan is a journalist who believes we have to ask the hard questions no matter whose interests are at stake. Sanity Fair is his weekly take on life, politics and society.