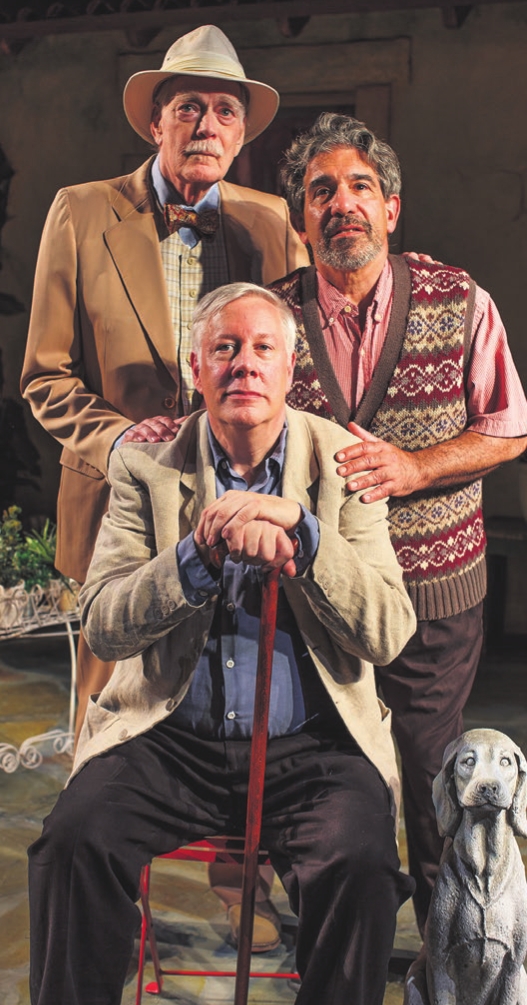

At first glance, the three veteran officers in Heroes—the season opener at Ithaca’s Kitchen Theatre Company—don’t look sufficiently disabled to have been confined in the old soldiers’ home for 41 years. The only visible wound is the bad leg of Henri (Arthur Bicknell), who hobbles with a cane, but he is often smiling. After a little while stocky and earthy Philippe (Eric Brooks) suffers a blackout from a piece of shrapnel still lodged in his head.

Tall, patrician Gustave (Evan Thompson), a recent arrival at the home, carries internal damage that comes more slowly to the surface. Mordant and acerbic, Gustave can disguise his inability to greet people on the street and re-enter society, but we see it. His attachment to the weighty statue of a dog is fetishistic. Nonetheless, he yearns to escape from comfortable confinement and take the others with him.

The year is 1959, as we are frequently reminded. The men’s wounds were delivered in World War I, not so long earlier in years as it might seem. The men could be the age of today’s baby boomers; both Bill Clinton and George W. Bush are 67. In their confinement, an economic depression, another world war and enormous technological change has transformed the world outside. The former colony of Vietnam, once a place for romantic escape, has been lost.

Inside the home there is only the counting of time. Simple ceremonies meant to cheer up the men, like the celebration of birthdays, have become occasions of dread. In a cracklingly witty early speech, Gustave laments the passage of each month, putting sunny August (when Frenchmen vacation) at the bottom.

If they were to escape their idleness, where would they go? Henri observes that if you go over the hill to the next valley, you find one that looks just like this one. The world of the men’s youth, with the music of Debussy, women in corsets and sharper social divisions, has completely vanished.

Heroes derives from the pen of French playwright Gérald Sibleyras (born in 1961), where it won acclaim under the title Le Vent des Peupliers (The Wind in the Poplars). Tom Stoppard’s translation won a 2005 Olivier Award in London, but he flubbed the title. Heroes says nothing about all the subtext of what on the surface sounds like a boulevard comedy. He was stuck: Any title beginning Wind in the . . . evokes Kenneth Grahame’s children’s classic about Mr. Toad, Wind in the Willows.

Lines about wind in the poplars are still in the dialogue, however. That’s because, students, poplars are deeply symbolic trees: They line the edges of cemeteries. Such notes do not exist in isolation, nor are they ominous. When Philippe is prowling the outer yards of the home he accidentally falls into an open, freshly dug grave.

The cheery surface in Heroes invites you to misinterpret it. Stoppard’s crisp dialogue and Margarett Perry’s assured direction guarantee the three men are good company. The wonder is all in the delivery because much of it does not look like much on the page. Some, however, is quotable.

Philippe: “When it comes to women we are not exactly at a loss for choice.”

Henri: “The fact that most of them are nuns is a bit of a drawback.”

For a while the audience might feel it is in a replay of another play about three Frenchmen talking, Yasmina Reza’s Art, also translated by a prestige Britisher, Christopher Hampton. The difference here is that the men are not talking about painting but life.

Similarly, the men’s surroundings are gorgeous. Kent Lynn Goetz’s lush set—with kind of a Proven�al fa�ade that would do credit to the Mirbeau Spa in Skaneateles, and warmly lighted by designer Tyler M. Perry—looks like a dandy place to pass the time. French veterans’ benefits, in the first year of Charles de Gaulle’s Fifth Republic, look generous. The absence of female companionship, which Henri has never enjoyed, prompts some silly speculation. In general, however, they want for nothing, and they are waiting for nothing.

In summary it must sound as though Heroes invites comparison with Samuel Beckett’s Waiting for Godot, but that’s pushing the men’s confinement too far. They never suggest that all life, or at least life outside the home, is meaningless.

A more likely antecedent for Heroes’ action is film director Jean Renoir’s antiwar classic Grand Illusion (1937), one of the most famous French movies of all time. Of the officers confined in a POW camp, it is tall, patrician Captain Boeldieu (Pierre Fresney) who feigns madness to prompt the escape of two companions. Like Boeldieu, Gustave, a fellow World War I aristocrat, is haughty rather than chummy. Notice his cruel remarks to limping Henri. It takes us a while to understand that Gustave’s grasp of reality falls behind that of nearsighted Henri, who ironically never sees the poplars. Henri must jettison good sense to accede to Gustave’s vision.

Despite its acclaim in Paris and London, Heroes has been little performed in North America. With all of Stoppard’s gifts, one suspects on this printed page it would offer the reader little. Its charm lies in the work it calls from three experienced actors. Evan Thompson, a newcomer here but a Broadway performer, allows Gustave more than his share of laughter and pain. Kitchen veteran Eric Brooks plumbs the mad nuances of Philippe, who fears that two patients having a birthday on the same day signals the exit for one of them. Arthur Bicknell, a community theater player as Henri, matches the subtlety and power of the two pros. This splendid production also features an atmospheric original score, written and performed by Anthony Mattana.

This production runs through Sept. 22