This year continues to mark the 200th anniversary of the War of 1812. The Onondaga Historical Association is hosting an exhibit from the National Museum of the U.S. Navy about naval activity during that war.

A local connection involves a man named Daniel Dobbins (1776-1856), a pioneer mariner on Lake Erie in the early 1800s. One of the most sought-after commodities in this era was salt, one of the few means available to preserve fish and meats before refrigeration.

An early history of Erie, Pa., states, “Previous to the war of 1812-14, a dozen or more vessels comprised the whole merchant fleet of the lake, averaging about sixty tons each. The chief article of freight was salt from Salina, N.Y., which was brought to Erie, landed on the beach … hauled in wagons to Waterford, and from there floated down … to Pittsburgh.”

Before canals, salt heading west left the shores of Onondaga Lake on boats run down the Seneca and Oswego rivers. At Oswego, the salt barrels were placed on a schooner, shipped to the Lower Niagara River, portaged around Niagara Falls, and then reloaded onto another sailboat for Erie. The trade totaled thousands of barrels annually.

Dobbins was one of the most active of these Lake Erie merchant captains. In 1809, he purchased a 90-ton schooner called the Charlotte and renamed the ship Salina, after the place that would be the source for most of its cargo: the village on Onondaga Lake. Sometimes he unloaded Onondaga salt at Erie, destined for Pittsburgh. Other times, he sailed up the Great Lakes to Mackinac and traded salt there for furs, which he brought to Montreal for great profit.

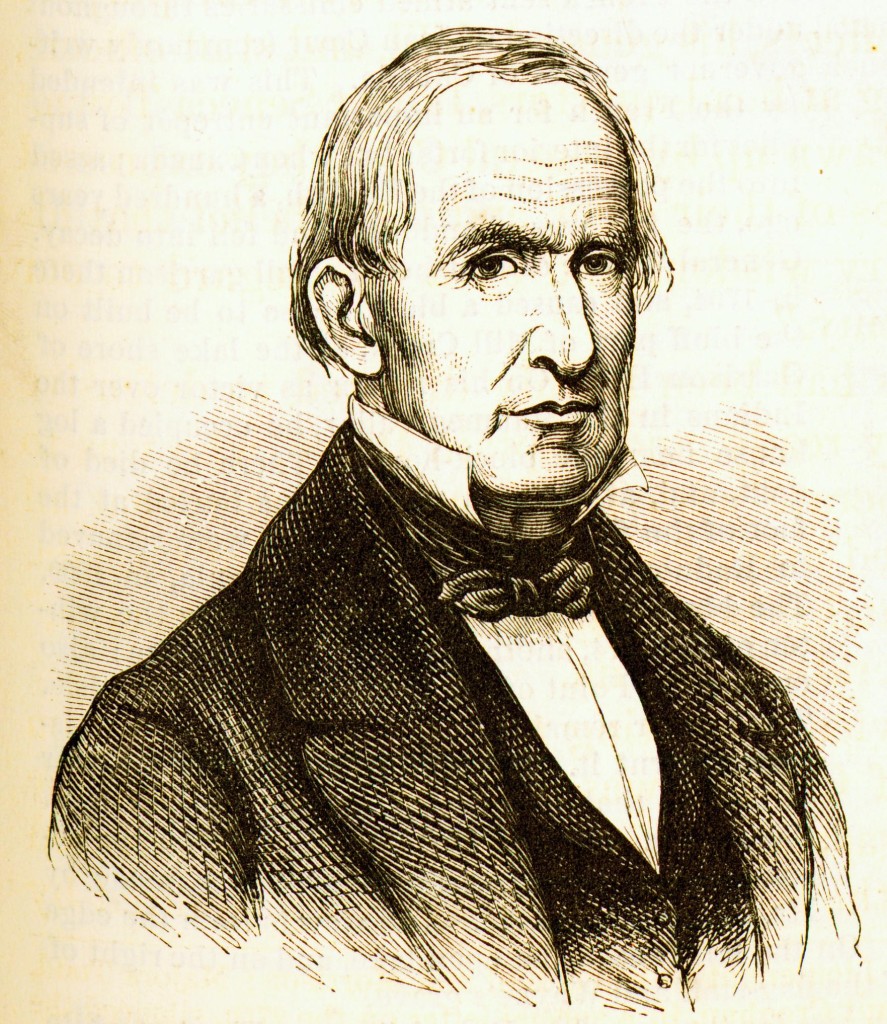

Photo: Onondaga Historical Association.

The United States declared war on Britain on June 18, 1812. Dobbins and the Salina were docked at Mackinac Island, at the head of Lake Michigan. The small American garrison, stationed at that island’s fort, was soon surprised by an enemy force of 300, which was 10 times its number. Dobbins and the Salina were temporarily commandeered by the victorious British and ordered to transport the paroled American prisoners to Detroit.

In August, a larger British force attacked and seized Detroit. Dobbins again found himself and the Salina in British hands. This time, the British kept the Salina to use as a supply ship. Dobbins, however, escaped.

The Madison administration in Washington knew it needed a naval fleet on Lake Erie or risk defeat on that front. Dobbins was asked to serve as a sailing master in the Navy and ordered to return to Lake Erie and establish a shipyard. He chose Erie, Pa., and Dobbins’ labors became the nucleus for the shipbuilding effort that would lead to creating Commodore Oliver Hazard Perry’s Lake Erie fleet.

Meanwhile, the British were using the former salt-hauling Salina to transport provisions and shipbuilding supplies among their Lake Erie posts in Canada. In December 1812, she was caught in Lake Erie ice and abandoned.

At the same time that winter, Dobbins and his construction crew were desperate for materials to outfit his unfinished gunboats at Erie. One day, to Dobbins’ surprise, a “ghost” ship appeared offshore, locked in the ice and abandoned. He organized a salvage operation, drawing sleds over the ice. Dobbins was no doubt amazed to find the ship that had drifted down the lake in the ice floe was his old command, the Salina.

Photo: OHA

It was a fortunate event. Dobbins decided to remove everything he could use. Desperately needed rope for rigging was taken. Scrap iron, rods and spikes from the Salina could be converted by blacksmiths into nails and fastenings for the ships that would become part of Perry’s fleet. Perry himself took over assembling the Lake Erie fleet in 1813, but Dobbins, the Great Lakes salt trader, continued to work closely with him on construction and supply details.

Their effort resulted in an American Lake Erie squadron of 11 vessels, nine of which confronted the British fleet at the western end of the lake in an epic naval battle on Sept. 10, 1813. The Battle of Lake Erie was a major American victory, immortalized with Perry’s report to his superiors: “We have met the enemy, and they are ours …”

The British defeat gave the Navy control of the Upper Great Lakes for the remainder of the war.

Dobbins had hoped to participate in this crucial battle. Perry, however, had given him command of the Ohio, a 59-foot merchant schooner with one gun. Perry assigned it to supply duties, and it was docked at Erie when the battle began. Three days later, Dobbins and the Ohio reached the victorious squadron and its captured prizes, carrying much-needed provisions for the weary and wounded sailors of both sides.

Dobbins continued with the Navy into the 1820s and then with the Revenue Cutter Service, a precursor to the U.S. Coast Guard. He left the salt trade behind, but getting Onondaga salt to market continued as one of the important drivers for internal improvements in the United States, especially for the creation of the Erie Canal.

Today, Dobbins lies buried at Erie. The hulk of the salt schooner Salina lies just a few miles away, beneath the waters of Lake Erie. Almost 200 years later, its small role in helping outfit Perry’s victorious War of 1812 fleet remains a provocative but virtually forgotten footnote in the lore of the Onondaga salt industry.

Dennis Connors is curator of history at the Onondaga Historical Association.