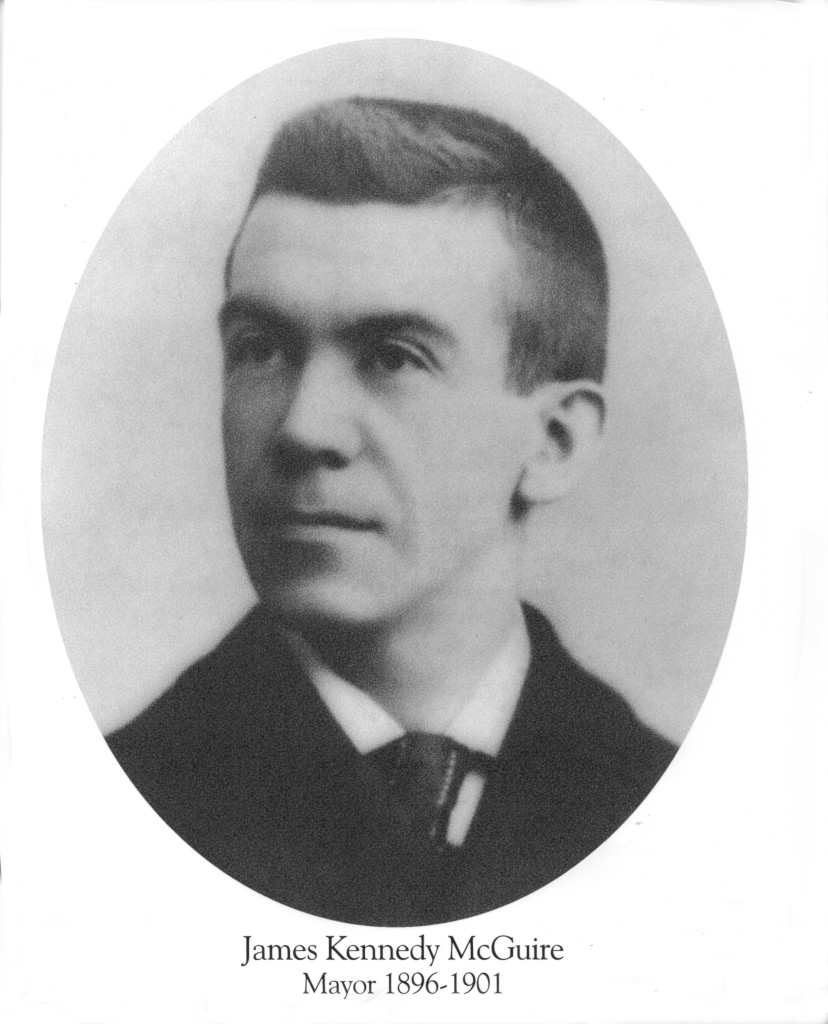

City of Syracuse Mayor Stephanie Miner says he was a “remarkable man” and “Syracuse’s own boy mayor.” James Kennedy McGuire (1868-1923) indeed began the first of his three terms as mayor of Syracuse in 1895 at age 27. A maker and shaker, he helped to change the face of the city by, among other things, pushing for the building of 38 schools and paving South Salina Street. Unlike any other local politician, he went on to make his fortune after leaving office. He also rose to national and international prominence and traveled with the powerful. Just before American entry into World War I, he published a jaw-dropping bestseller, arguably the most controversial book ever to come from any Syracusan.

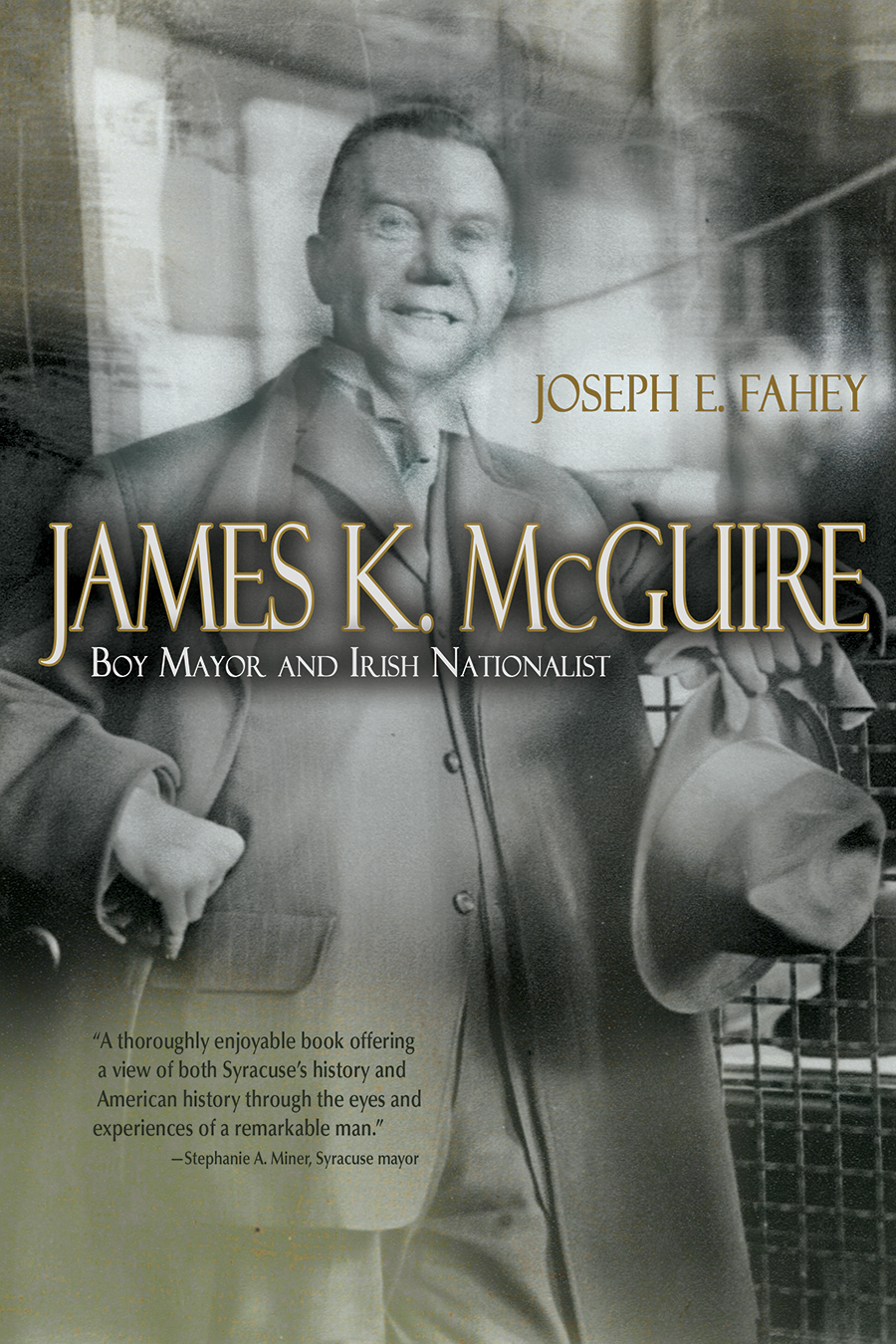

Rivaled only by Horatio Seymour, the mayor who ran for president against Ulysses S. Grant in 1868, McGuire is easily one of the most colorful and dynamic figures in Syracuse history. Despite creative efforts of the Onondaga Historical Association, that’s still a subject on which many of us know too little. Addressing this gap is a new book from Syracuse University Press, James K. McGuire: Boy Mayor and Irish Nationalist (hardcover, 280 pages, $24.95), by Joseph E. Fahey. An adjunct professor at the SU Law School, Fahey has researched McGuire’s life, both in and after Syracuse, exhaustively. As an author Fahey benefits from an inside track: James Kennedy McGuire is a maternal great-uncle, giving Fahey access to family lore and other unpublished material.

The McGuire family had emigrated from Enniskillen, County Fermanagh, in what is now Northern Ireland. James was born in New York City before the family moved to Syracuse to enter the shoemaking trade. They lived mostly on the near North Side, once residing at 149 N. Salina St. The Erie Canal was a marked presence then, not always welcome. James’ brother Frankie drowned in it, possibly the victim of anti-Catholic bullies, a trauma that weighed heavily on the family. In the multi-ethnic city, the Germans were thought to have run the best schools, and so the family decided to send James there, where he took instruction through the German language. This experience would affect his life in unexpected ways over several decades.

Economic necessity deprived McGuire of the chance to finish high school, but he nonetheless became a skilled wordsmith, both on the printed page and on the platform. He early became associated with the Catholic Publishing Company, producers of The Catholic Sun, which is still with us. Without formal training, he early emerged as a powerful public speaker, favoring Democratic party policies and Irish nationalism. This was before public address systems. He was only 19 when he spoke before a labor convention at the old city hall and an even larger group on the shores of Onondaga Lake.

Irish concerns, then represented by remnants of the failed Fenian movement, gave McGuire a national stage. Flaming the still burning embers of passionate crowds, McGuire drew more than 10,000 people to Ogden Park in Chicago. Strange to say, one of the personages most taken with McGuire’s oratorical skills was a putative enemy: legendary Republican Party operative Mark Hanna, the Karl Rove of his day. Hanna advised returning to Syracuse and running for office, even if was for the Democrats.

Making his first run for the top of the local ticket required all of McGuire’s silver-tongued adroitness, but also great luck. Getting the nomination first meant upsetting the local Democratic machine, run by former Mayor William Burns Kirk (still remembered for the South Side’s Kirk Park). The Republicans, with an edge in registration, should have been more formidable but they were split. The larger faction was headed by party boss Francis Hendricks (donor of SU’s Hendricks Chapel), who promoted Charles G. Baldwin, and the other by Congressman James Belden, who favored Charles I. Saul.

An imaginative campaigner, McGuire reached out to Syracuse’s small African-American community, which until that time had voted Republican, the party of Lincoln. Along with his other gifts, McGuire also gained by campaigning speaking German in the North Side’s German neighborhoods. Election night brought McGuire a plurality of 3,300. His address at that time was 203 Green St., in what we now call the Hawley-Green District.

An unexpected reward of reading James K. McGuire: Boy Mayor and Irish Nationalist is in seeing those names from streets and buildings attached to dramatic personalities. Among the most vivid of these is the young mayor’s annoying adversary, saloonkeeper and alderman Frank Matty, a fellow Democrat, the scourge of the city council. McGuire vetoed 60 of the council’s measures. Among them was one to charge impoverished bootblacks a $25 license fee to ply their poverty-level trade. But the council fought back, overriding 40 of his vetoes.

He wanted more schools. Of the 40 that existed in the city in 1908, 38 were McGuire-sponsored. McGuire pushed for the building of the first city-owned golf course, in Burnet Park. A lover of the arts, he supported the establishment of the first Everson Museum on the North Side. What he could not get the city do to, he led by personal action. Most importantly, he persuaded philanthropist Andrew Carnegie to build the ornate library at the corner of Montgomery Street and Columbus Circle.

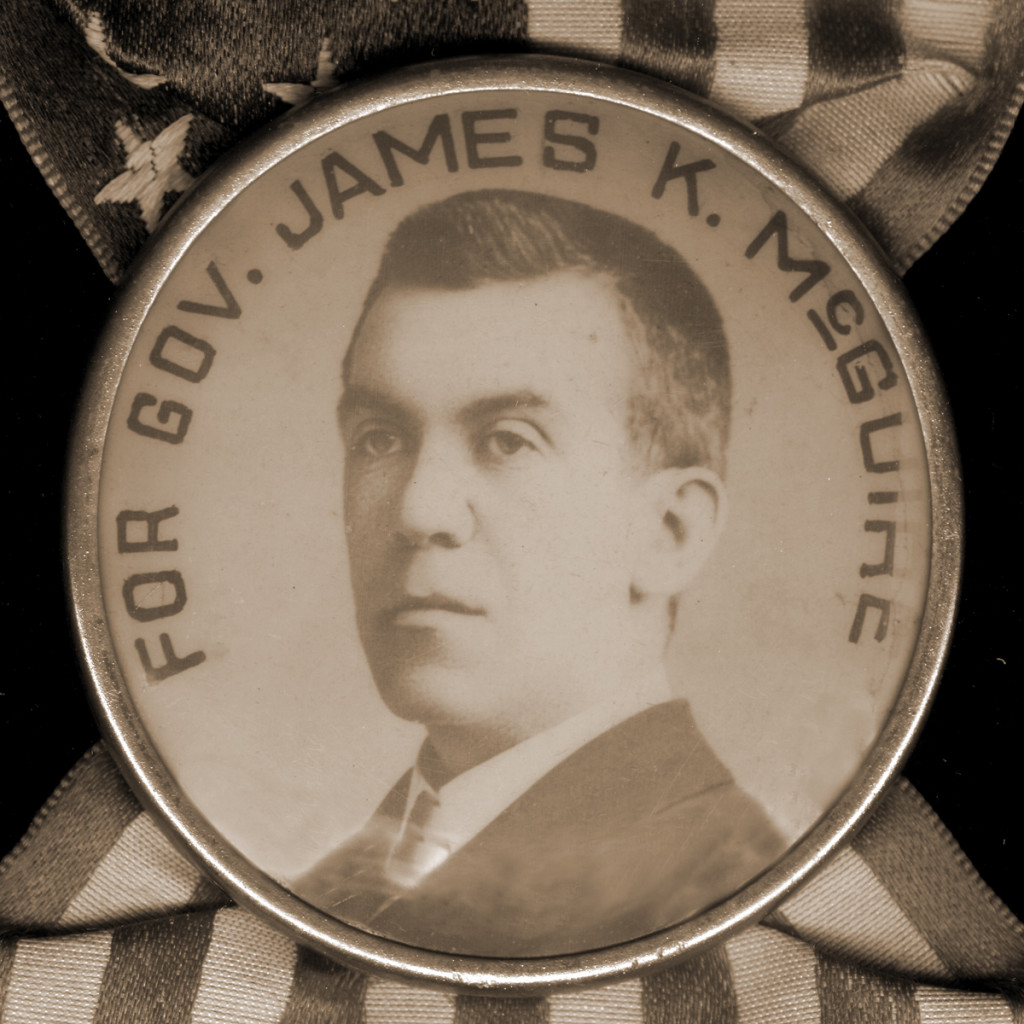

Not yet 30, McGuire’s star was rising when he defeated Donald Dey of the department story family. His name was bruited about to run for governor, which would have pitted him against another youngster, Theodore Roosevelt. But the machinations of Tammany Hall and its boss Richard Croker would not allow it. For his third run, McGuire defeated patrician Theodore Hancock, owner of one of the most celebrated of all Syracuse names. But three two-year terms was all there was going to be. At the end of 1901, McGuire was an ex-mayor, age 33. He passed on running for the U.S. Congress on a ticket that would have been headed by gubernatorial candidate William Randolph Hearst. Instead, he would go in new directions.

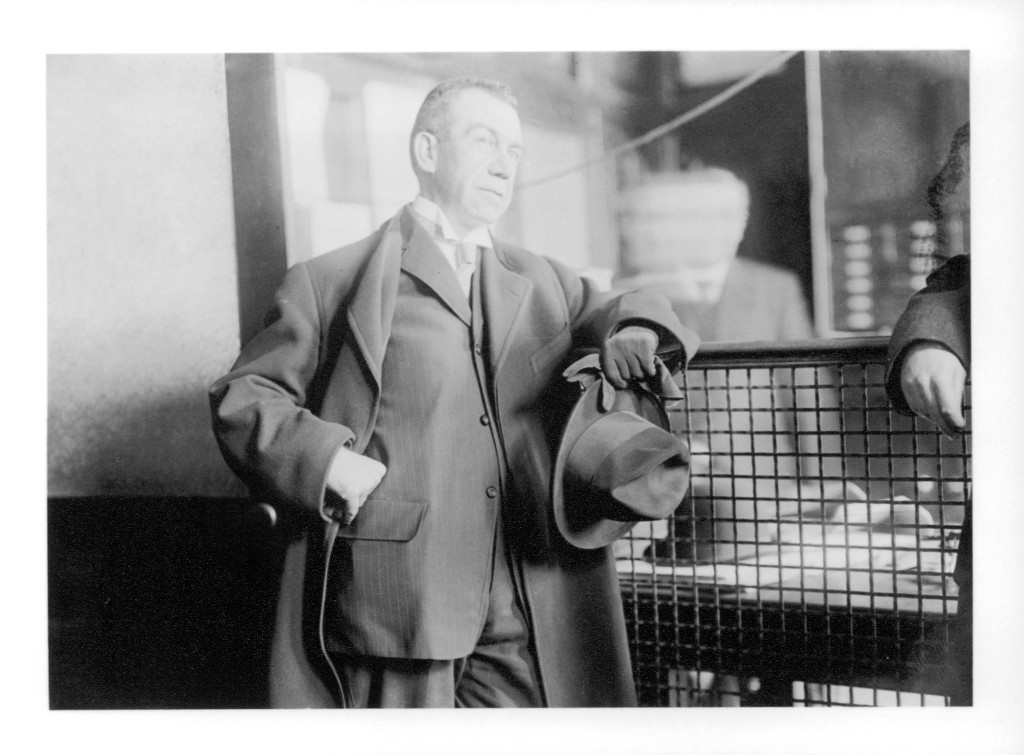

After a few years in the insurance business, McGuire became a lobbyist for Barber Asphalt Company of New Rochelle, and in 1910 he moved to that city, staying there until 1921. The proximity to Manhattan changed many things. He became better acquainted with national figures, both those campaigning for Irish freedom, and prominent Democrats. One was the thrice-defeated presidential nominee, William Jennings Bryan, who would become secretary of state in the Woodrow Wilson administration. McGuire would also become affluent.

The arrival of the automobile meant that all the roads in the nation had to be paved. Nearly all of them would be paid for with public money. The former mayor of a city of 100,000 was ideally suited to understand that different jurisdictions could be fanatically specific about the requirements of the chemical and physical composition of the asphalt to be laid. Although the years in the asphalt trade appear to be unrelated to the Syracuse years of the exciting last five years of his life, they are the most turbulent. Disputes over money led to lawsuits and subpoenas. Battling Frank Matty and the city council seemed tame in comparison.

McGuire’s heartfelt commitment to Irish nationalism came to dominate the center of his life. This meant intense study of Irish history, geography and politics. He maintained links to American organizations supporting Irish independence, such as the Gaelic-named Clan-na-Gael. He was fascinated by shadowy, secret organizations, such as the Irish Republican Brotherhood, and ultimately by the famed Irish Republican Army. All these tensions moved into high gear when war broke out unexpectedly between England and Germany in August 1914. Could the enemy of Ireland’s oppressor be Ireland’s friend?

Germany had actually been Ireland’s friend for some time. German scholars learned how to decipher the Old Irish language and explored Ireland’s ancient ruins when the ruling English either ignored or disparaged them. It should also be remembered that the Imperial German Army of World War I, despite its bad press in Belgium, did not behave as monstrously as the Nazis of World War II did.

Quite a few Irish nationalists were openly pro-German. Famed Irish anthropologist and public intellectual Sir Roger Casement was hanged as a traitor for his putative pro-German activity. British forces intercepted boats full of German arms interested for Irish rebels. This was a sentiment shared by many Irish-Americans. Victor Herbert, Dublin-born composer of popular operettas Babes in Toyland (1903) and Naughty Marietta (1910), loudly championed the German cause, at a high personal price.

The most strident voice in this chorus belonged to the North Side-educated James K. McGuire in his The King, the Kaiser and Irish Freedom (1914), far and away his most famous work and still very much in print. It was followed by What Germany Could Do for Ireland (1915). The author’s thesis could not have been clearer. He urged Irish-Americans and the United States itself to favor Germany in current conflict, assuring that the defeat of Britain would free Ireland of centuries of oppression. The books were banned in Britain and Canada and made for a hard sell in Anglophile America. As the United States drew closer to war, McGuire’s friendship with Secretary Bryan proved useful.

McGuire’s relationship with Eamon de Valera, the key figure in 20th-century Irish politics, led to the Boy Mayor’s last adventure. The American-born de Valera was the only one of the rebels from the Dublin Easter Rising of 1916 to escape the firing squad. After a daring jailbreak in early 1919, de Valera made his way to the United States raising money for bonds supporting the new state to emerge from the then-raging Irish War for Independence. Hosting a fugitive from British justice was a dangerous undertaking, but de Valera knew he had a safe haven at the McGuire home in New Rochelle. Bold as brass, de Valera’s main fund-raiser was held at the Waldorf Astoria.

James K. McGuire was only 54 when he died of a heart attack at the Hotel Raleigh in Washington, D.C., on June 29, 1923. Huge crowds attended his funeral at St. John the Evangelist, and he is buried in St. Agnes Cemetery.

The premiere

The launch for Joe Fahey’s book James K. McGuire: Boy Mayor and Irish Nationalist (Syracuse University Press) will take place 4:40 to 6:30 p.m. May 21 at the Onondaga Historical Association.

Books will be available for purchase. The event will include a talk by Fahey and a book signing.

The launch is free and open to the public. Refreshments will be sponsored by the Irish American Cultural Institute.

![Facebook-460x56-(re)DiscoverTheAlternative[1]](http://syracusenewtimes.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/03/Facebook-460x56-reDiscoverTheAlternative1.png)