Sixty-two years ago, Sam Feld was ready to start teaching high school social studies in Syracuse when a letter arrived at the Syracuse school district office.

“Gentlemen: Just for your information, Sam Feld, Harrison Street, is a Communist leader and organizer,” read the anonymous note. “He graduated in education. I hope he will never teach our children.”

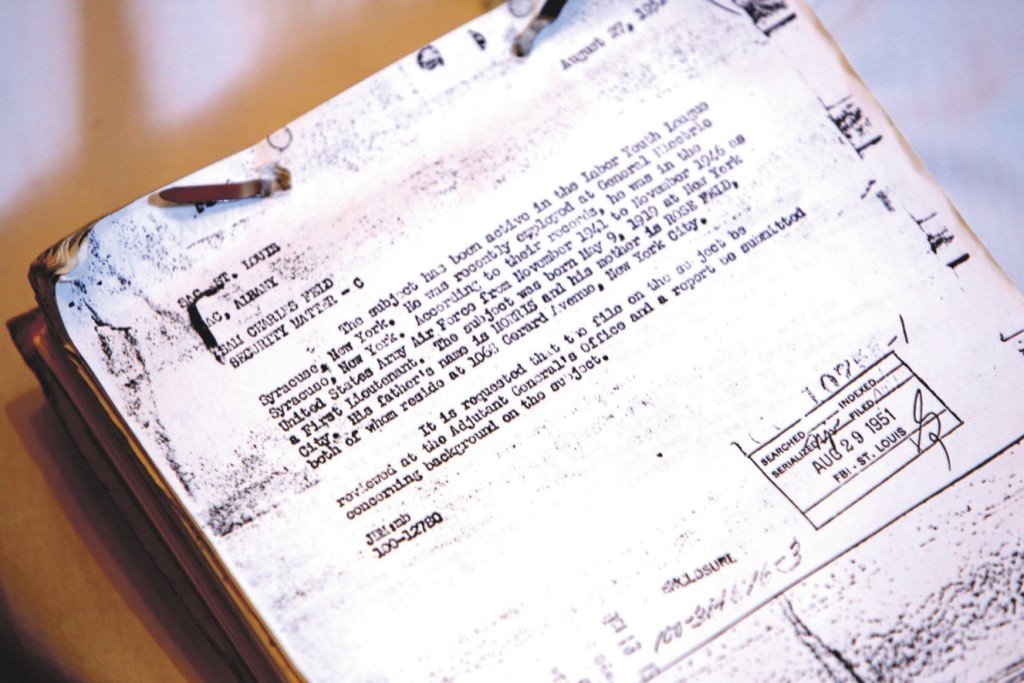

“Unfortunately, I got my degree during the McCarthy period,” says Feld, now 94. He gestures toward a thick FBI dossier about him that he keeps as a grim souvenir. “It was not a happy time, to know your phone was probably tapped, that you were being followed.”

The era named for Wisconsin Sen.

Joseph McCarthy touched the lives of countless Americans. Seizing on Cold War tensions with the Soviet Union and postwar jitters in the new nuclear age, McCarthy launched a crusade in 1950 to expose communists and others he claimed were subverting American government and values. Although he never uncovered any communist plots, McCarthy’s anti-communist zeal spread across the nation.

Washington and most state governments held hearings, passed laws against subversion and adopted loyalty oaths that were copied in the private sector. While the Communist Party itself was never banned, any association with the party was considered grounds for suspicion, investigation and dismissals. These laws and regulations eventually were repealed, found unconstitutional and overturned by the courts.

But between 1947 and 1955, more than 179,000 Americans were “screened,” and at least 12,000 workers lost their jobs: civil service employees, teachers, college professors, union and office workers, librarians, journalists, entertainers and others. Some Communist Party leaders went to jail. An atmosphere of suspicion and intimidation had a broad chilling effect on free expression and political participation that lingers to this day.

Sam Feld, like many others, felt the sting of McCarthyism even before he could find a job.

“I got my master’s,” he says. “There were a couple of leads from the Education Department, but when the dossiers went to these two schools, that was the end of it.”

A neighbor of Feld’s in the Syracuse University area, Charlie Wollowitz, 85, still isn’t sure why his old friend was rebuffed while he, who also joined the Communist Party, was hired by the same district years later. But he has an idea.

“He was going through the employment service at SU,” Wollowitz recalls, noting there was at least one anti-communist activist in the office at the time.

“She was defending the faith, so she would have blown the whistle.”

She and McCarthy both were gone by the mid-1960s, when Wollowitz got his teaching job. But loyalty oaths remained a potential pitfall, even for former communists. Wollowitz says he was ready to deny party membership, but the subject never came up.

“Nobody asked me if I was or wasn’t,” he says, “and I wanted a job and needed a job.”

While Sam Feld became a salesman, Wollowitz’s long teaching career at Nottingham High School expanded to include classes at Le Moyne College that ended with his retirement in December. Today, Wollowitz contemplates the two old comrades’ divergent paths and sighs.

“You think you just dilly-dally through life, smell the daisies, have a drink, smile at people and shake hands,” he says. “And life is a little complicated.”

Mary Ann Zeppetello also came on the Syracuse job market in the 1960s. She and her late husband, Nate, had split from the party years earlier.

“Whatever loyalty oath I signed, it was not fraudulent,” she says, explaining that she and her Syracuse comrades always were patriotic Americans who loved their country, saw its faults and worked to bring about change. She moved smoothly from graduate school at SU to a job with Onondaga County’s mental health services, then with the state. “By then, they changed the wording from ‘have you ever been a member of the Communist Party’ to ‘are you loyal to the United States,’” she notes.

Zeppetello’s politics did shut off one career option. “My husband used to say, ‘It’s too bad you were a member of the communist party, because you should have run for office,’” she says. “But that was out of the question.”

Instead, Zeppetello, now 82, built a successful counseling practice that continues four decades later. In 1983, she was named Social Worker of the Year. In 2002, she received the Peace Award from Peace Action of Central New York. She also was recognized by state Sen. John DeFrancisco (R-Syracuse) for her work on behalf of victims at the site of the 9/11 terror attacks.

“Not bad for a girl from the North Side,” she jokes.

Changing times played a role in the careers of these three former communists. While Wollowitz was growing up in the 1940s, there was already nostalgia on the left for the radical 1920s and 1930s, when Feld was young. The Communist Party once claimed 80,000 members. They helped to build labor unions and to promote civil rights and integration. American communists marched in annual May Day parades and ran for office. In the early days, a few even won. During World War II, Zeppetello and other teenagers cheered the Soviet Union, then America’s staunch ally in the fight against Hitler.

By 1956, though, the party’s fortunes had turned. Battered by McCarthy-era attacks, American comrades also had grown disillusioned by Soviet totalitarianism and were increasingly dubious about prospects for communism at home. The three Syracuse communists had endured surveillance and harassment, but they also had shared comradeship and solidarity. Their stories recapture a startling era when political ideology and cultural norms collided on the streets.

‘The word came down …’

Feld grew up in the Williamsburg section of Brooklyn.

“My father had a little store at 157 Havemeyer St.” he says. “There were pushcarts all along that street.” As Feld recalls, there were just two political choices in his neighborhood: “You either became a socialist or a communist.”

After graduating from high school, Feld went to work for his father. He served as a B-17 bombardier in World War II, participating in a rare U.S. landing on Soviet territory.

“I was an admirer of the Soviet Union, ushering in a new economic system,” he interjects, adding ruefully: “They mucked it up terribly.”

After the war, he went to college in Illinois on the GI Bill. There, he met Jane Berkman, a Syracuse native and ideological soul mate. The couple married and returned to Syracuse, where he enrolled in a master’s program and had three children in three years. Blocked from teaching, Feld sold sewing machines for Sears, Roebuck & Co.

Sam Feld, now 94, worked as a salesman after someone sent an anonymous note to the Syracuse school district telling of Feld’s participation in the Communist Party. “I hope he will never teach our children,” the note said. He never did.

“Then the word came down, and I couldn’t work there anymore,” he says.

Eventually, he found long-term employment in pharmaceutical sales with a politically sympathetic boss.

Like Feld, Wollowitz grew up amid the zesty politics of Brooklyn, Brighton Beach in his case. His parents both emigrated from Belarus before World War I. From a chance encounter with other immigrants at Coney Island, Wollowitz says, he learned his father had been a “red hot communist.” Family lore tells of the new immigrant refusing to register for the U.S. military in World War I, declaring, “I will not kill.”

At Brooklyn College, Wollowitz was surrounded by communists and began his up-and-down relationship with the party. He still remembers a conversation with classmates.

“One of the young people was saying, ‘Why isn’t this the time for revolution?’” Wollowitz shakes his head at the memory. “Who is going to fight this revolution, two kids in a third-period class?” Near the end of World War II, Wollowitz volunteered for the U.S. Maritime Service (“I found it incredibly exciting”). Afterward, he went back to college. . . and dropped out (“It was boring”). By then, he had discovered upstate New York through a summer farm-study program. Wollowitz went to work as a toolmaker in New York, married and started a family.

His move to Syracuse in the early 1950s coincided with a decision by communist leaders in New York City to “colonize”—to branch out and escape the red-baiting that was taking its toll.

“They asked some people who were freer than others, who tended to be young—I was young—if they would sort of move to new places where they weren’t known,” he says.

Wollowitz quickly found work as a toolmaker. He had a third child, remarried and eventually became an art teacher.

Zeppetello, a Syracuse native, says she always seemed to have a rebel streak. She felt the sting of discrimination early, as an olive-skinned Italian girl in an Irish neighborhood. She says the kids across the street “always called me ‘darkie.’” The headstrong teenager switched from parochial to public school, then chose Central over North High School. “There were no black people and no Jews there, so I transferred,” she explains.

She found her way to jazz clubs and Sunday dances in the old 15th Ward. “I saw a world out there, and I wanted to partake in the dinner,” she says, “and the breakfast and the lunch!” She won a scholarship to SU, where she discovered the Communist Party. “Most of the students were from New York City,” she remembers. “Some of them were children of very leftist parents.”

A high school friend introduced her to Nate Zeppetello, a labor organizer, World War II vet and local Communist Party leader. In 1949, the couple decided to wed, but when Mary Ann asked her parish priest to marry them, he insisted they first renounce communism.

“He wanted to be the next Fulton Sheen,” she explains, referring to the anti-communist cleric of the McCarthy era.

She said the couple was married a few days later by a sympathetic black minister in the 15th Ward who subscribed to The Daily Worker, the Communist Party newspaper. The newlyweds spent their honeymoon in New York City, where they sat in on the sensational trial of communist leaders who eventually were convicted of subversion under the Smith Act.

In 1956, Monsignor Walsh, who knew the couple since childhood, performed the Catholic marriage rite at Our Lady of Pompeii.

The Zeppetellos had three sons. While Mary Ann stayed home with the boys, Nate found work with family members in the heating and air conditioning business, avoiding the McCarthy-era blacklist.

“We could survive and not have to worry so much.” Housing, too, was a challenge.

“Because Nate was openly a communist, it was difficult to rent,” Mary Ann says. They managed, she says, by living in family-owned apartments.

Zeppetello still thinks her public support of the Rosenbergs had personal repercussions. In 1953, the nation was transfixed by the trial of Julius and Ethel Rosenberg, who were convicted of passing atomic secrets to the Soviets and executed the next year. Zeppetello received a letter from the Jewish Community Center asking her to withdraw her son from child care because “he needed his mother,” she recalls. “But I’m convinced it was because my name was in the paper, at the height of the McCarthy era, with the Rosenbergs, and they didn’t want any child of a known communist in their center.”

By the 1960s, she adds, “the climate had changed.” They moved to the East Side and became members of the JCC.

‘Friends were losing jobs …’

In 1956, the Zeppetellos were ready to quit the party.

“It was a loss, because it was a place during that period where you could put your hopes and your actions together,” Mary Ann says.

In prior years, though, the party had been in full swing in Syracuse. As early as 1949, Nate and Mary Ann Zeppetello stood with SU student Irving Feiner as he was arrested for making a civil rights speech from a ladder on Harrison Street. Feiner was urging his listeners to attend a meeting that evening where noted civil rights leader O. John Rogge spoke on behalf of the Trenton Six, black youths on trial for murder. Four of the six were found not guilty, one died in jail and the sixth was exonerated.

The Syracuse communists joined forces with local progressive groups and demonstrated outside the Federal Building downtown. They leafleted at the gates of General Electric, Carrier Corp., and Pass and Seymour.

In 1951, an FBI informant described Mary Ann as an “explosive” young communist leader. In March 1954, Zeppetello was called to testify before the Subversive Activities Control Board in New York City. She says she wore a red dress to the hearings. The Syracuse Herald Journal, noting she did not “name names” of fellow party members, headlined its story, “Syracuse Woman Mum at Red Quiz.”

Zeppetello attended a Communist Party leadership camp at a farm south of Syracuse. Local communists mingled at an annual summer picnic at the rambling Cazenovia estate of two “fellow-travelers.” This kind of stimulation and comradeship helped to sustain the Syracuse communists.

“Friends of mine were losing their jobs,” Feld recalls. “Even in the face of facts—seeing the destruction that was taking place in the Soviet Union because of this dictatorial edifice—I still wanted to believe. Part of it is to be part of a family, part of a group.”

“There was a closeness with your comrades,” agrees Zeppetello. “Don’t forget the word was ‘comrades.’ It meant you had direction, you had a shared purpose, you had a vision of a better world.”

Wollowitz still reveres U.S. communism’s heritage, which dates back to the Arbeter Ring—mutual aid societies that grew into the International Workers Order. “Finnish groups, Swedish groups, all of them had a core of people who were very strongly left,” says Wollowitz.

“There was a very rich tapestry of people on the left. The sense of fraternalism was very much with them.”

‘You were careful …’

Outside the warm circle of Communist Party comradeship in the 1950s, unnamed informants in Syracuse were gathering evidence for the FBI.

“It’s possible that they came by and picked up our trash,” says Zeppetello.

The informants scrutinized receipts and compiled expense accounts for Nate and Mary Ann’s trips. They kept records of Nate’s writings, and logged the Zeppetellos’ comings and goings for more than a decade—three fat files’ worth. Although Mary Ann dismisses the dossiers as “boring,” and indeed they contain no bombshells, the sheer bulk of the files is daunting. Informants’ names are blacked out.

The FBI’s unnamed agents also tracked Sam Feld’s activities: meetings attended, speeches heard, discussions about disarmament, fair housing, Korea, the Rosenbergs. “I was sorry for them,” Feld says of the informants, speculating that they “probably capitulated to the FBI, fearful of their jobs.”

One entry in Feld’s dossier from 1960 veers close to satire.

“Advise that subject’s three children are under 10 years of age,” it reads. “No indication has been received from this or other informants that these infants are engaging or being influenced in CP affairs.”

Understandably, the surveillance fostered paranoia within party ranks.

“You begin to question if the informants were those closest to you,” says Zeppetello. The harassment cast a pall over normal socializing. “You were careful not to be very public,” she says. “We did not hang out with the Felds and their kids. . . We were very protective of them publicly.”

At their most expansive, the Syracuse communists dreamed of influencing public policy and changing society. At the other extreme, they worried about being sent to internment camps. As Smith Act prosecutions continued into the 1950s, some party leaders changed addresses and even changed their names to protect themselves.

Feld’s FBI dossier depicts him as a “courier” for an “underground leader of the Communist Party in Syracuse” in 1953. Feld recalls what the errand was.

“He, like many other leaders, went underground, fearful that they were going to be caught, convicted and sent to jail,” he recalls. “And he wanted to meet with his wife again. So I picked his wife up here in Syracuse and drove to Ithaca to meet him.”

Mary Ann Zeppetello says American communists deserve more credit for their pioneering advocacy of social reform and civil rights.

“Communist Party members were taking chances with their lives in the 1940s and 1950s, long before the civil rights movement of the 1960s,” she says. She recalls traveling with a black comrade to a still-segregated Washington, D.C., for a Civil Rights Congress in 1949, a gathering that later would be labeled suspicious by the McCarthyites.

“We got there at night,” Zeppetello remembers. “We had to hide Jim on the floor when we got near Washington. . .

We sneaked him into a house after dark and out before dawn. We went to breakfast, and they wouldn’t serve him at the counter.”

Like the Zeppetellos and the Felds, Wollowitz drew away from the Communist Party in the later 1950s. But he always had been bothered by rigid ideologies—and their contradictions. His unease surfaced at an early protest rally in Brooklyn.

“They were all screaming, ‘No free speech for fascists! No free speech for fascists!’ And in my mind was: How do you determine what a fascist is?” Wollowitz’s ambivalence toward the party line deepened as art led him toward abstract sculpture. “You have to address the working class,” he explains, “and it’s only realism that will do this. Abstraction is selfish, self-indulgent. So it always created a barrier for me.”

Still, Wollowitz grows wistful, thinking of the old days. “The things you valued, you felt were values shared by many more people than you,” he says.

‘I believed…’

The U.S. Communist Party also suffered as economic prosperity took hold. But so did the influence of a discredited Sen. Joe McCarthy, along with fellow anticommunists marginalized by the advancing civil rights movement. Wollowitz could be speaking for both the reds and their zealous foes when he describes the fantasies of the McCarthy era.

“There’s always a sense people have of magnifying who they are, what they do,” he says.

Were communists ever a real threat to American democracy? Zeppetello scoffs at the notion.

“My husband was a first lieutenant in the U.S. Air Corps,” she says. “He flew 34 combat missions. When he got out of the service, he gave his gun up.” The communists were never out to overthrow the government, she adds. “They were on trial for thinking.”

With active party membership a faded memory, these three former communists remain committed to their ideals.

“The orientation is in many ways still there,” says Wollowitz.

Feld says he never considered himself a disloyal person. “I believed what we were doing,” he says.

Zeppetello says she would not join the Communist Party today, although she continues to work for peace and social justice. “There will always be people who are bleeding,” she says. Quoting Harry Belafonte, one of her heroes who also was affected by the red-baiting era, she adds: “I can’t live any other way.”

The communists in Syracuse wanted a fairer world, not revolution, says Feld. “It was just ordinary, good people.” He suggests the anti-communist backlash posed a greater threat to America’s security. “The most important thing it did was to scare the multitude from taking any action,” he says. “So people didn’t join, and the Communist Party just disintegrated.”

Even today, Joe McCarthy casts a long shadow—long enough that Zeppetello hesitated before revealing her ancient Communist Party membership; long enough to give her pause when an interviewer asks her to identify fellow party members, raising ghosts of the inquisitors from more than half-a-century ago.

She says the names would reveal doctors, dentists, professors, laborers, bakers, teachers, housewives, social workers, blacks and whites living everyday lives in Central New York. Many have moved away. Many have died.

“This puts me in a predicament,” she says. “What do I do if I talk to you about these people? Am I ‘naming names?’”