Many courtroom dramas suffer from the Hamilton Burger syndrome. Burger (played by William Tallman on television) was the hapless prosecutor who nearly always lost to Raymond Burr’s Perry Mason for the defense. And our sentiments were always pinned on Mason anyway, no matter how assiduously Burger struggled.

Real drama, as opposed to melodrama, calls for conflict, where we could conceivably be rooting for either side. The issue is even tougher when the trial is based on history, as it is for Jerome Lawrence and Robert Lee’s Inherit the Wind. Seasoned director Sharee Lemos addresses these problems through bold and deliberate casting for this Central New York Playhouse production.

Lawrence and Lee claim their 1955 stage play is set “somewhere in America,” but there is scarcely a single person who enters without knowing its prime antecedent is the Scopes “Monkey Trial,” on the legality of teaching evolution in Tennessee schools in 1925. Further, no one needs Cliff’s Notes to see that the bombastic former presidential candidate who aids the prosecution, Matthew Harrison Brady (Joe Pierce), is based on William Jennings Bryan, and the agnostic, acerbic defense attorney Henry Drummond (Tom Minion) speaks for Clarence Darrow. And we know how the trial and the historical perception of it worked out. How are a director and actors going to get our juices going?

To begin with, as Lemos says in her program notes, Lawrence and Lee are not exactly being disingenuous with us. Interrogation in the trial is meant to evoke the tactics of demagogue Joseph McCarthy during the 1950s Red Scare that just preceded the play’s opening. In this it is like Arthur Miller’s The Crucible, not really so much about the Salem witch trials as it is about the present.

Thus Lemos, who thanks God in her program bio, does not think Christian faith is on trial in Inherit the Wind. This is why her casting choices are so significant.

Both Joe Pierce and Tom Minion are familiar faces in community theater, and Lemos has worked successfully with both of them before at Appleseed Productions. She cast Minion as Christian thinker C.S. Lewis in Shadowlands (September 2011), a project close to her heart, and deployed Pierce to prove that Atticus Finch does not have to talk like Gregory Peck in To Kill a Mockingbird (May 2010).

The 58-year-old play is still performed because its two poles can be aligned with oppositions in U.S. culture—such as that of the rural South and the urban North.

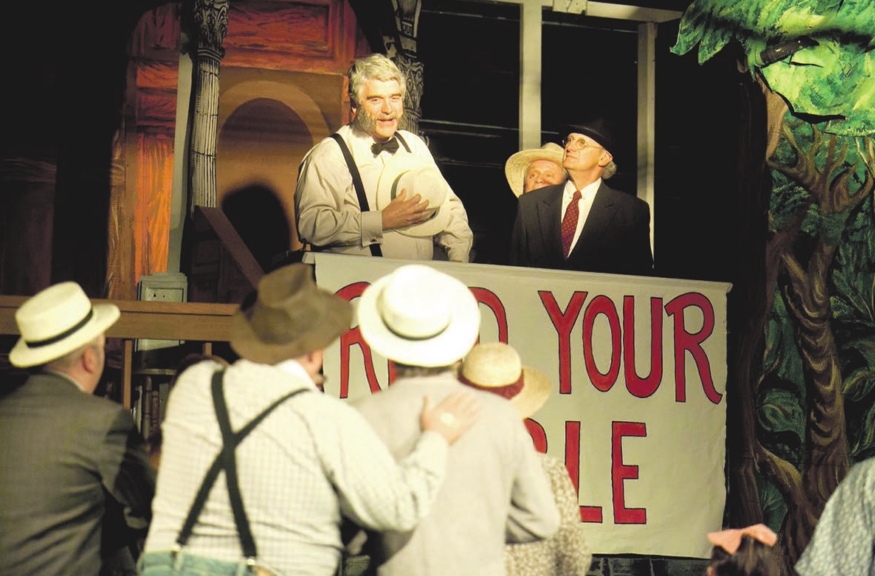

Pierce has the larger task, also the potentially less-rewarding one: human ize Brady. In much of blue state America Brady is seen as a blowhard and a bully, which is what director Stanley Kramer asked Fredric March, wearing a bald cap, to do in the heavy-handed 1960 movie version. Lemos and costumer Barbara Toman put Pierce into a fat suit and thick, gray, leg-of-mutton sideburns, but still draw on Pierce’s off-stage persona. He’s one of the most popular players in town, known for his generosity and willingness to volunteer for dirty grunt work, like building stages.

What you get from Pierce then is the most lovable Brady ever seen, a man to charm the townies, even if he lost three times running for president. No prig, his little failures, like an overindulgence in sweets, are endearing. His roseate compliments, Protestant editions of blarney, win hearts if not votes.

In contrast Lemos asks Minion to underplay Drummond, even though he has some of the juiciest lines in the play. Stanley Kramer, defining the conventional interpretation, cast Spencer Tracy, the Tom Hanks of his day, for the movie. Minion, instead, is anti-heroic, a gadfly who can’t quite deliver his sting. The sense of futility he feels when the judge (Bob Lamson) overrules his reasonable requests is numbing rather than enraging. He might be speaking for the values of the playwrights, but he is no triumphalist.

This pitting of two reliable good guys changes the readings of more than a dozen lines. When Brady proclaims that he has come to defend the “truth of scripture” and decries of the “blasphemies of science,” he sounds heroic rather than misguided. Inherit the Wind continues to be performed, including four times on television, because the two poles it represents can be aligned with a number of binary oppositions in American culture. Here it looks like a dialogue between the populist, rural South and the secular, urban North.

Brady’s real adversary is the sneering journalist E.K. Hornbeck (Edward Mastin), a stand-in for H.L. Mencken, who indeed covered the Scopes trial. His lines may be even richer than Drummond’s, but his real prominence is as the most visible observer at the trial. When Drummond’s cleverness unties Brady’s strained logic, it feels like a fall of a tribune of the people before his enemies.

Central New York Playhouse has recently been devoted to large-scale musicals, filled with thunderous dancing feet. Here it puts 21 players in motion to demand that you think about old questions in new way.

This production runs through Oct. 26.

See Times Table for information.