Jukin’ Bone’s induction into the Syracuse Area Music Awards (Sammys) Hall of Fame this week entails a certain irony. For starters, Jukin’ Bone wasn’t even the real name of the band.

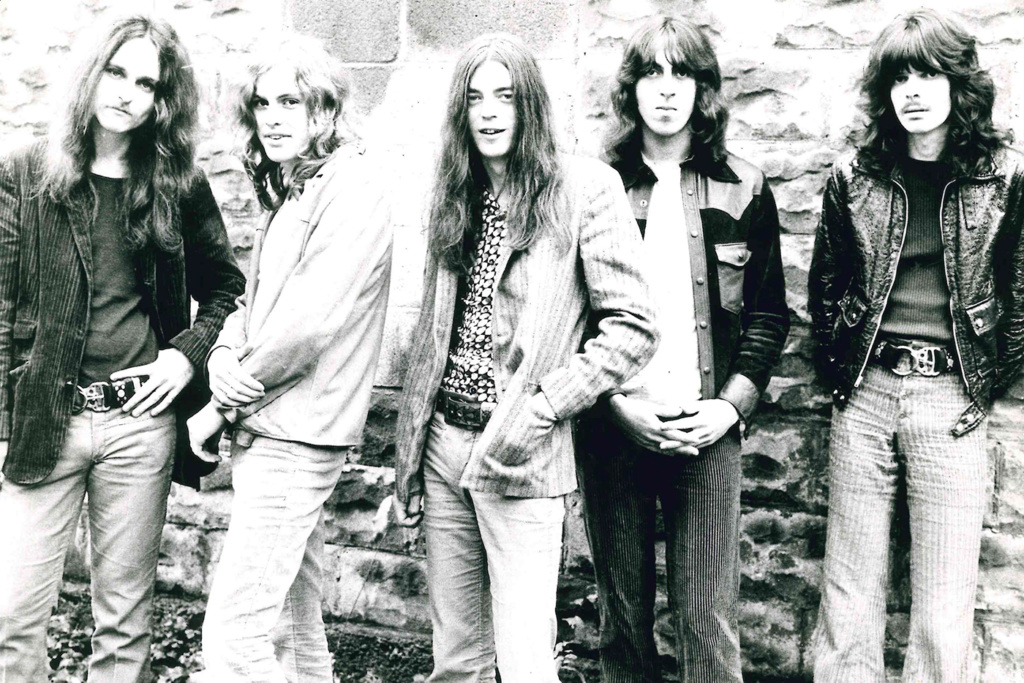

The relentlessly rockin’ quintet was called Free Will, led by guitarist Mark Doyle and vocalist Joe Whiting. The band also featured second guitarist George Egosarian, bassist John DeMaso and drummer extraordinaire Tom Glaister. An earlier version of Free Will included Bill Irvin on rhythm guitar and Barry Maturevitz on bass.

After drawing record crowds from 1968 to 1971 at nightclubs, high schools and colleges up and down the Thruway, Free Will signed a $35,000 three-LP recording contract with RCA that had been secured by Concerts West. The band had successfully showcased at Wheels, a Manhattan nightclub on the Upper East Side.

Free Will became one of three area rock acts to ink major-label deals in the early 1970s. They joined Jam Factory (Epic) and Ronnie James Dio in Elf (Purple Records/MGM) to take a stab at national fame and fortune.

Before the band plugged in at Jimi Hendrix’s legendary Electric Lady Studio in Greenwich Village, however, RCA demanded that Free Will change its name.

“We came up with the name Jukin’ Bone, somehow,” Whiting said last week. “RCA found the name Free Will kind of esoteric, especially given the hardness of the band. I think George (Egosarian) was involved. Jukin’ Bone sounded hard.”

Free Will made its bones as an ultra-exciting live act, as documented by the band’s independent 1970 LP, Live at Jabberwocky, highlighted by a breathtaking seven-minute-26-second version of “Ridin’ with the Devil.” The outfit hoped to capture its live sound at Electric Lady.

“The producer, Lewis Merenstein, had seen us (performing live) in good circumstances, and he advised us to make a live record,” Whiting recalled. But the band decided to try to capture its live sound in the studio.

“Then we made the first of many foolish mistakes by taking some time off, about two months without playing out, and then went straight into the studio,” Whiting said. “So we were stiff.”

Merenstein, then 37, had been making records since 1959. His credits ran the gamut from Charlie Musselwhite to the Spencer Davis Group, from Charlie Daniels to George Burns. He helmed the Jukin’ Bone sessions for the nine-track LP, to be titled Whiskey Woman.

“Lewis had produced Van Morrison’s Astral Weeks and Moondance, and Mama Cass’s first solo record, so he had good credentials,” Whiting said. “I really think he was a jazzer at heart.” Perhaps that’s why the cover art for Whiskey Woman depicted a marquee for Roseland Dance City, although New York City’s Roseland Ballroom owner Louis Brecker had famously banned rock’n’roll at that Manhattan music landmark.

For Whiskey Woman, Merenstein and the band eschewed studio tricks in favor of running through all or most of the nine tunes every night, then choosing what were deemed the best. All tracks were recorded completely live in front of a small, invited audience.

Doyle remembers the studio buffet table well-stocked with liquor and cocaine. “Everybody was getting high in those days,” he said. Self-described Free Will hanger-on Dave Rezak, later to become Syracuse’s top booking agent, confirmed that the Whiskey Woman sessions were “well-lubricated.”

“But we weren’t out of our heads,” Whiting insisted. And the performances — while not as riveting as their live shows — were more than respectable, exuding an authentic hard-rockin’ blues groove on originals such as “Jungle Fever” and “Got the Need,” as well as covers of Aretha Franklin’s “Spirit in the Dark” and Booker T’s “The Hunter.”

While the rhythm section created a solid foundation, Doyle’s dynamic guitar work, which ranged from cascading single-note solos to eerie, slippery slide, and Whiting’s ardent, aching vocals carried the day … or night, as the case may be.

But Whiskey Woman fell short of the band’s and RCA’s expectations. It failed to sell, and wasn’t even embraced by Free Will’s fan base in Central New York. “No one was happy with the first LP,” Whiting said.

Doyle heard longtime local fans griping, too. “One guy told me, ‘Man, you got screwed in the production.’”

Even before Jukin’ Bone could atone for the first album’s failure — in fact, before Whiskey Woman was even released — the band was already pulling apart. Drummer Tom Glaister was the first to call it a day, and rhythm guitarist George Egosarian was also itching to leave.

So a few months later, when they waxed Way Down East, Glaister was gone and not one but two drummers, Danny Coward and Kevin Shwaryk, took his place. “Tom was a monster drummer,” Whiting recalled, “and we thought the best way to replace him was with double drummers.”

This time producer Lewis Merenstein and the band, now working at RCA Studios, were better focused, and the result was a decidedly more polished recording.

“I actually prefer the second record,” Whiting said. “We performed better.”

“We were straighter,” Doyle pointed out.

But even more than moderation, Way Down East benefited from a renewed approach embracing the benefits of studio technology. “The second album was a studio record: no live audience, no running through all the songs each night,” Whiting said. “Instead we recorded song by song, so it was more of a studio effort,” complete with overdubs.

“Joe sounded better,” Doyle said, “and the record sold better.”

RCA released the soaring, sexy “Cara Lynn” as a single, and the album’s other nine tracks displayed the band’s strengths. For instance, Doyle lays a biting slide guitar over a funky bass groove on “Nightcrawler,” adds a swampy electric piano on “Mojo Conqueroo,” and Whiting leads a nasty, shout-along version of “See See Rider.” The band also bravely belied its hard-edged image with an acoustic tune, “Yes Is Yes”

Following the 1972 release of Way Down East, Jukin’ Bone toured with ZZ Top, Freddie King, the Allman Brothers, The Kinks, John Mayall and Three Dog Night, among others.

“Jukin’ Bone was one of the most electrifying live bands you will ever see,” said Syracuse music authority Ron Wray. “They went on tour but never received enough promotion across the country, although they perhaps came very close to national stardom.”

On July 14, 1973, drummer Danny Coward departed, leaving Jukin’ Bone as a four-man group: Doyle, Whiting, DeMaso and Shwaryk.

“We were dealing with lots of internal friction,” Whiting recalled. He and Doyle tended to blame each other for the band’s many missteps. “Management left, and others we wanted gone. We realized it was over.”

When they had signed with RCA, they were bluntly informed that if their records tanked in the market, the band would be released from their contract. “It never occurred to us that we wouldn’t sell,” Whiting said with a laugh. But after Way Down East came out, the band was dissolving and RCA canceled plans for a third disc.

“Things had not worked out the way we’d hoped they would,” Whiting said. “Some of it was our own fault, but it wasn’t all our own doing.”

Of the $35K that the company poured into Jukin’ Bone, Doyle said the musicians only pocketed about $250 each. “But we didn’t care, as long as they kept us high.”

The primary problem, as Doyle saw it, was that “Nobody was looking out for you. People wanted to hang out and party with the band, but they should have been taking care of the band.”

Whiting thinks Jukin’ Bone fell victim to a rock’n’roll Murphy’s Law: “The truth is, and this is what I always say about Jukin’ Bone, that everything that could go wrong did go wrong.”

Sammys Events

Three Jukin’ Bone members — Joe Whiting, Mark Doyle and John DeMaso — plan to attend the Syracuse Area Music Awards (Sammys) Hall of Fame induction ceremony on Thursday, March 2, 7 to 10 p.m., at the upstairs room of the Dinosaur Bar-B-Que, 246 W. Willow St. Syracuse University instructor David Rezak will introduce the trio. Whiting and Doyle were previously inducted into the Sammys Hall of Fame in 1996. And Free Will reunited to perform at the inaugural Sammys Awards show at the Landmark Theatre in 1993.

Other 2017 inductees include guitarist-songwriter Meegan Voss, the Oneida County jam-band moe. and guitarist-bandleader Paul Case. Music Educators of the Year Anthony and Patricia DeAngelis will also be honored. And the Sammys Lifetime Achievement Award will be presented to Vincent Falcone, the longtime Las Vegas pianist and former music director for Frank Sinatra, Robert Goulet and Pia Zadora.

Tickets for the ceremony cost $25, available at SyracuseAreaMusic.com.

The Sammys Awards ceremony will be staged Friday, March 3, 7 p.m., at Eastwood’s Palace Theatre, 2384 James St. Performers include moe., the Spring Street Family Band, Curtis “Tallbucks” McDowell and the Brownskin Band with Bobby Green, Chris Taylor and the Custom Taylor Band and The Ripcords with the Boneyard Horns. Tickets cost $20, and are available at the Sound Garden, 310 Jefferson St., and SyracuseAreaMusic.com.

Sammys Nominees

- Best Pop: Sir Magnus, Ben Mauro, Jenna Cunningham, Dave Novak, The Jess Novak Band

- Best Jazz: The Carol Bryant Trio, Bob Holz, Second Line Syracuse, Edgar Pagan, Peter Maciulewicz

- Best Hip-Hop or Rap: Steve Cook & Cyph, Oxburg, World Be Free, OHSO Loud

- Best Americana: Stephen Douglas Wolfe, Shane Pas’cal, Driftwood, The Easy Ramblers, Mary Ann Casale

- Best Alternative: Townhouse Warrior, Anthony and the Mountain, The Stacy White Suite, Bell & Sgroi, The Alpha Fire

- Best Rock: Dom Cambareri, New York Flyers, Son Bully, King Chro and the Talismen, Irv Lyons Jr.

- Best Hard Rock: Bruce Campbell, Spire, Breaking Solace, Level VII, Murder in the Rue Morgue

- Best Other Style: The Spirit of Syracuse Chorus, Syracuse Society for New Music

- Best Jam Band: Count Blastula, Joe Driscoll & Sekou Kouyate, Baked Potatoes, Root Shock

- Best Folk: Lauren Mettler, Falling Waters Trio, Sheralyn Jeanne

- Best Singer-Songwriter: Lauren Mettler, Savannah Harmon, Byron Lee, Alanna Boudreu

- Best Blues: Mike DeLaney & the Delinquents, Tas Cru, Skip Murphy & His Merry Pranksters, Funky Blu Roots

- Best R&B: Sean McLeod, Alani Skye, Mark Macri