Sporting a purple polka-dotted smoking jacket, David Broda leaned and rocked to the beat of St. Germain’s “Rose Rouge,” playing on his classic 1200 Technics turntable. The sound system projected the jazz tune with booming clarity through his garage-converted-record-collection-shrine off his Jamesville home, a space he calls Funky Butt Hall.

“You gotta have a great, ass-kicking sound system,” says Broda, 62, who started disc jockeying in the mid-1970s. “You gotta have a booming system or else, forget about it.”

Broda pivots, walks toward one of 13 boxes brimming with 12-inch records, and extracts two. He places Mixmaster Gee’s “The Manipulator” and Grandmaster Flash and the Furious Five’s “The Message” on the turntables. “People used to go nuts when I put this on,” he says about “The Message,” positioning the needles in the grooves.

Michael Davis Photo | Syracuse New Times

Backtrack to the early 1970s, when Broda was a Syracuse University student. (He graduated in 1974 with a bachelor’s degree in photojournalism and has worked at the university since 1980, now at the Photo and Imaging Center.) He frequented his friends’ parties on Lancaster Avenue, where his passion for music, which focused mostly on jazz, expanded. He watched them spin records and quickly became interested in the deejay scene.

In 1977, he and fellow deejay David Morton dreamed up and hosted the first Cyber Funk Affairs, an annual concert they held at The Creamery in LaFayette. They spun Afro-funk, jazz, rhythm’n’blues, gospel, and Latin music, but “never, ever rock’n’roll,” Broda says. “We were all about playing an incredibly eclectic spectrum of music.”

Michael Davis Photo | Syracuse New Times

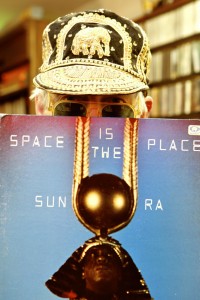

With hundreds of people on the dance floor for hours, the blowouts gained a cult following. Each Cyber Funk Affair had its own theme, and Broda and Morton their own deejay personas and costumes to match. As the Doctors of Funk, they wore hospital scrubs; as the Sonic Absorbers, egg crate foam mattress toppers were fashioned into jackets; and as the Nuclear Underwater Fishermen, the vinyl spinners sported mushroom cloud hats.

Morton impacted Broda’s interests through the years. “His parties and record collection had a big influence on me in developing my musical tastes. I could not have done it without him,” Broda says. “He is still my best friend to this day.”

They played hundreds of records at the Cyber Funk Affairs. “I tried to take the listener on a journey,” Broda recalls. “I might start way, way back and then slowly, through the course of the evening, build up to a point to peak the dancing.” Broda notes that this reflects an old-school deejay method; today’s focuses more on “drop after drop after drop,” he says.

Broda cites “The Message” and the Propellorheads’ “Take California” as peak party tracks, while and FC Barnes’ “Rough Side of the Mountain” used to “blow up the house,” he says. Tito Puente was “huge,” he adds, and James Brown a “no-brainer.”

To accumulate his collection, which includes about 5,000 records, Broda went crate digging at album stores and ordered hard-to-find vinyl from France and Japan. “It came from an addiction to finding the perfect groove,” he says.

Michael Davis Photo | Syracuse New Times

Once the Cyber Funk Affairs’ run ended, Broda spun platters for the openings of Pastabilities in 1982 and Club Zodiac in 1991. Yet an after-party at Syracuse Stage following the 1984 performance of Angel City holds a very special memory for Broda.

“The next day we were having brunch at Phoebe’s and we noticed (jazz drummer) Max Roach sitting a couple tables away,” Broda says. “Roach got out of his chair, walked over to us, and said, ‘You guys were good last night.’ We both just plotzed.”

Broda, who deejayed all his gigs for free, enjoyed the long hours at the turntables because it gave him time to build up to those peaks throughout the night. But another element made performing even easier.

“You gotta realize, you’re in a space with a hundred people and they’re drinking, smoking, doing whatever illicit drugs they want, especially Ecstacy. That was like a deejay’s best friend,” he says. “I wasn’t taking Ecstacy: I wouldn’t be able to deejay. But people basically got completely screwed up, which definitely made playing a little bit easier.”

Broda owns a not-for-sale promotional radio station copy of The Winstons’ “Amen Brother,” which gave the world the six-second “Amen” break that Broda calls “the genesis for all of sampling.” He also owns “Take California,” featuring a photograph of O.J. Simpson carrying the Olympic torch before the 1984 Los Angeles Olympics, and a box of James Brown 45s, among thousands of others.

Broda feels the deejay music culture changed with the advent of CDs in the 1980s and, more recently, the boom in downloading and streaming online. “There used to be more mystique around it,” Broda says. “Downloading has removed the tactility of it all.”

Adapting to the changing scene, Broda switched from deejaying (his last gig was at Spark Art Gallery in 2011) to making mixed CDs for “anyone who is interested,” making the cover artwork in Photoshop, giving each CD a title, and printing the track list on the opposite side of the cover photo. The 80-minute limit is a drawback, but Broda makes unified CDs with songs he hears online and from his record collection. In this sense, his CD-making embodies the same goal that DJing does: “to make it cohesive, and take the listener on a journey from start to finish,” he says.

“CDs are not quite as tactile as records,” Broda says. “There’s definitely a movement to get back into vinyl. Maybe it’s just a nostalgia thing.” Even so, Broda guesses he bought his last record about seven years ago: Dap Dippin’ with Sharon Jones and the Dap-Kings.

The vibe in Broda’s office at SU represents a modern take of the music scene. He plays a station characterized by “down tempo electronica, ambient, chill-out” music on MixCloud and stores a box of his mixed CDs under his desk.

But even though he has adapted to the technological developments surrounding music, Broda still makes time for Funky Butt Hall to listen to records and to deejay—less for an audience, and more for himself.