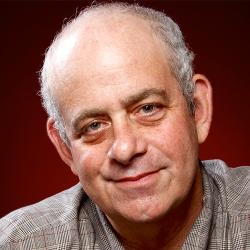

In 1940, a 12-year-old Jewish boy and his parents flee Nazi Germany to start a new life in the United States.

Seventy-seven years later, his son applies for dual citizenship with Germany, so he’ll have somewhere to go if he has to flee Nazis in the United States. Crazy stuff, but crazy is what you get when you install a criminal psychotic into the most important job on the planet.

By now you’ve no doubt figured out who the applicant for German citizenship is. Ist ich!

And, no, this isn’t another of my larks. I’ve already contacted the German consulate in Boston. I’m not worried. The Syracuse football team has a better chance of defeating Clemson than I do of having my petition for German citizenship denied.

A German repatriation law for Jews who fled Hitler — and their direct descendants — makes me a virtual Jew-in. Same for the wife and kids. Mein papers are in order. Sieg Heil that, baby.

The back story: If history had been allowed to meander on its natural course minus the intrusion of Hitler, my late father, Kurt, would have come of age as a German. Most likely, he would have inherited his father’s successful furniture store in Karlsruhe, Germany, which, in turn, would have been inherited by his progeny.

Let me spell it out for you. If not for the Nazis, the person who would have been me — my father’s firstborn child — would likely be the furniture king of southwestern Germany, the Dunkel & Brightwurst of Baden-Württemberg, if you will.

Things turned out differently. Thanks to a brave Catholic relative who scouted ahead for Gestapo, Kurt and his parents, Arthur and Johanna, escaped Germany and Austria by train and made their way to Chicago, missing out on that whole Final Solution thing.

Historical note: The Final Solution had two sides: the Undesirables (Jews, homosexuals, Gypsies, Roman Catholics, the disabled, the mentally ill) and “some very fine” Nazis who were goaded into operating the gas chambers.

How fortunate my dad and his parents were to get out with their lives. Theirs is a story of courage, hope, luck and the indomitable human spirit.

The only downside is that instead of becoming a German furniture magnate, I’m now a bitter, misunderstood white man writing for pocket change. Talk about marginalized. Even the Nazis don’t want anything to do with me.

So, Germany is looking more and more like a real possibility. I like it there. I lived in Cologne for three months in 1984 as a foreign exchange student. Almost everyone spoke English even then, which was helpful because the only German I knew upon arriving was the Chicken Dance.

I lived with a lovely German family, the Fischers. They were so suspicious of authority, even their own, that they felt compelled to explain why their young son, Bjorn, was so mouthy. “We don’t discourage our children from talking back because we want them to learn to stand up to authority,” Mr. Fischer told me. My kind of place.

A few years ago I returned to Germany, this time to Berlin, where I learned an important lesson: Absinthe is a powerful intoxicant and demands a stronger presence in this country. Also, I got to see the future of Donald Trump’s border wall. The infamous Berlin Wall, which once cruelly cleaved the city, now consists of a few slabs for tourists.

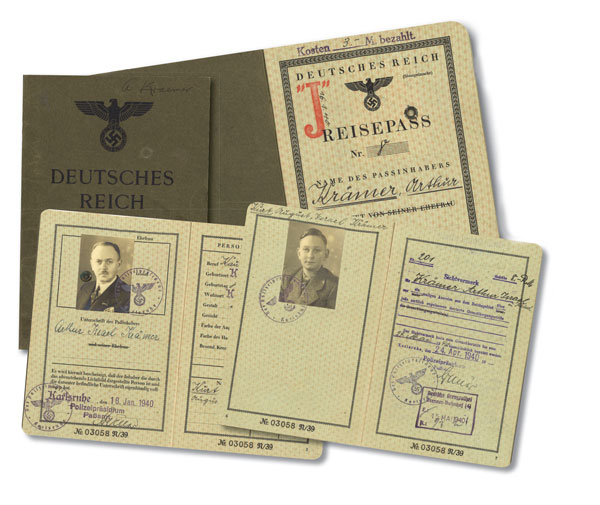

This won’t be easy for me. I realize that some aspects of life in the United States cannot be duplicated, like Buffalo wings and NFL Commissioner Roger Goodell lying through his teeth. I’d miss that, but this is no time to get sentimental. I’m gonna get me some German passport, one that doesn’t have a red letter “J” stamped on it like the Nazi-issued Reisepass that my grandfather and father had to carry.

I can’t help but wonder if this was all meant to be. Arthur, my grandfather, was awarded the Iron Cross for bravery in World War I for stringing telegraph wire over a live battlefield. That didn’t help him 23 years later when he was rounded up at Kristallnacht and interned for weeks for the crime of being Jewish.

Once in Chicago, he sold stationery door-to-door, but the tug of the Vaterland remained strong. Despite the horrors he experienced there, he returned to Germany in the 1970s to live out his final years. Will the same tug pull me in? Do they even make lederhosen in my size?

I’ll keep you posted as the application process unfolds. Rest assured that I will continue to file humor columns for the Syracuse New Times even if I’m forced by totalitarian terror to relocate to Germany. That’s where we are, folks. Time to practice my Chicken Dance.