Four Christian churches stand on the Onondaga Nation: Wesleyan, United Methodist, Episcopal and Seventh-day Adventist. But there’s no Roman Catholic Church on the territory near where Catholic missionaries, including French Jesuit priest Simon Le Moyne, visited in the 1650s.

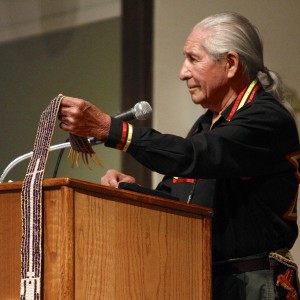

The Catholic Church is not welcome on the Nation because of the disrespect Jesuit missionaries showed when they tried to convert Haudenosaunee to Christianity, Onondaga faith keeper Oren Lyons said Friday, Nov. 15. The 20 months the Jesuits lived at St. Marie among the Iroquois, from 1656 to 1658, did not represent a peaceful mission. It was an attempt to colonize and destroy the culture of the Haudenoaunee, the original inhabitants of the area, Lyons says.

“No one could withstand the organized power of the Roman Catholic Church,” he says.

Lyons’ comments came during a sometimes tense two-hour event at Le Moyne College (named after the Jesuit missionary) that was part of a two-day symposium called Listening to the Wampum. The symposium, organized by groups including the Onondaga Historical Association and Ska-nonh – the Great Law of Peace Center, aimed to challenge the dominant historic interpretation of the contact between the French Jesuits and the Onondaga in the 1650s.

The written record of the Jesuit Relations, letters the missionaries sent to their superiors, has long been the only source of the story. The Haudenosaunee record their history in wampum belts, made of purple and white beads. One wampum, known as the Jesuit Belt, or the Remembrance Belt, refers to the period when the Jesuits visited Haudenosaunee and built a mission at the edge of Onondaga Lake.

“Our interpretation {of the belt} is, ‘Don’t ever forget what they were going to do,’” Lyons says.

The symposium and Ska-nonh (at the site of the former St. Marie mission known to generations of Central New Yorkers as the “French Fort”) seek to include the Haudenosaunee view to offer a broader historic context and assist in a reconciliation process.

“There’s no question from the Jesuits’ perspective the central motive was mission activity,” says the Rev. Robert Scully, a Jesuit who teaches history at Le Moyne.

But, he added, the 17th-century Christian attitude about evangelization has changed, as have views of slavery and women’s rights.

“At least on a relative scale, the Jesuits tended to be somewhat more open to other cultures,” he says. “By no means did all Jesuits have those views, but those were the ideal.”

Further, he says, in some sections of the Jesuit Relations, “a Native voice breaks through.”

Before the Europeans came to what they considered the new world, indigenous people treated each other with respect, Lyons says. “That wasn’t shown to us very well by our brothers across the sea,” he says.

The Jesuits criticized the Haudenosaunee as heathens who worshipped nature, he adds. “We said we respect nature,” Lyons says. “We know what it does.”

The main concern of the Haudenosaunee is to protect the Earth, Lyons says, pointing to the historic damage the recent typhoon caused in the Philippines.

“It’s going to get worse until we change our ways,” he says.

Audience members shared several ways the Jesuits could heal relations with Native Americans. They include helping to convince the Vatican to repudiate 15th-century Doctrine of Discovery, which justifies the takeover of land by Christians from non-Christians; the return of wampum belts thought to be at the Vatican; and reparations for mistreatment of Native Americans in boarding schools.

Lyons acknowledged that the discussion was an important step toward reconciliation. “I’m not angry,” he says. “It’s a real waste of energy to be angry. It’s up to them {the church} to do more than apologize.”

President Obama’s Comments

President Barack Obama referred to Haudenosaunee tradition Nov. 13 in a speech during the White House Tribal Nations Conference.

“I know we’ve got members of the Iroquois nation here today,” Obama said. “And I think we could learn from the Iroquois Confederacy, just as our Founding Fathers did when they laid the groundwork for our democracy. The Iroquois called their network of alliances with other tribes and European nations a ‘covenant chain.’ Each link represented a bond of peace and friendship. But that covenant chain didn’t sustain itself. It needed constant care, so that it would stay strong. And that’s what we’re called to do, to keep the covenant between us for this generation and for future generations.”

Onondaga spiritual leader Tadodaho Sid Hill and Onondaga faith keeper Oren Lyons were among hundreds of Native leaders at the event in Washington, D.C.

Obama pledged to focus on four areas to improve life for Native Americans:

- Strengthening justice and tribal sovereignty.

- Expanding opportunity for Native Americans.

- Ensure access to quality, affordable health care.

- Being good stewards of Native homelands.

Watch Obama’s speech