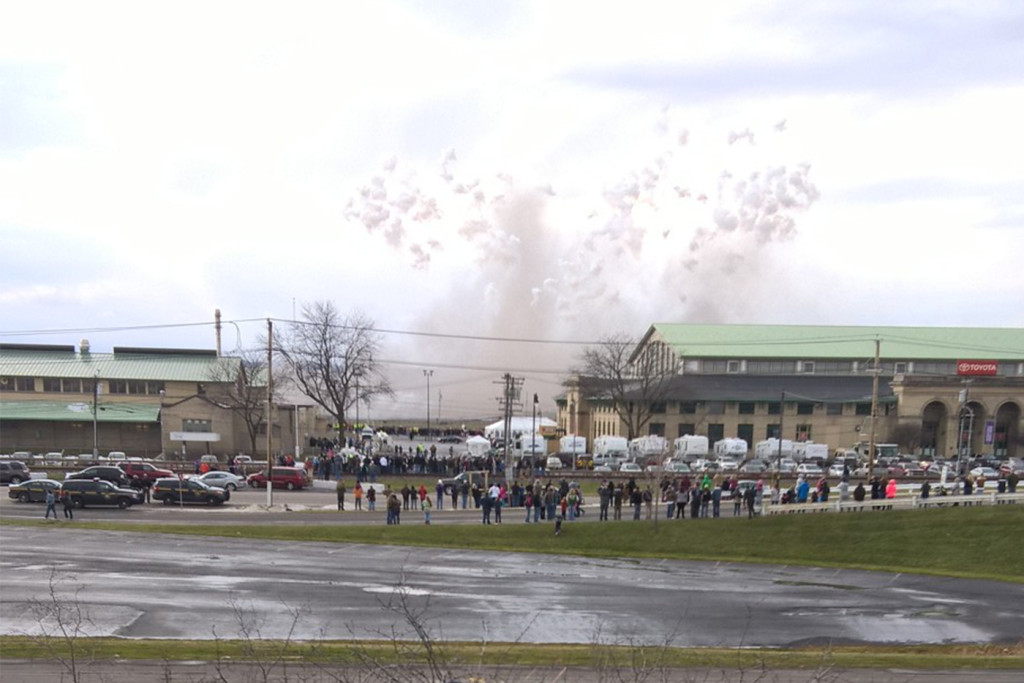

Anytime a building implodes in Syracuse and civic leaders are expecting it to happen, it should be cause for celebration. To a select few, the demolition of the fabled New York State Fair Grandstand was exactly that.

To the Maryland contractor (What’s the deal? No one in upstate New York knows how to blow stuff up?), it was a handsome payday. To the monied equestrian class, it was a jolly hoof to the groin of those grubby dirt racers, whose hallowed mile oval lies in ruins. To Gov. Andrew Cuomo and his upstate lady friend Joanie Mahoney — their hands cupped lovingly over the plunger — the blast was a romantic metaphor worthy of Shakespeare.

“These violent delights have violent ends

And in their triumph die, like fire and powder

Which, as they kiss, consume.”

To borrow the county exec’s insult, what an “emotional” moment it was. Under threatening skies on Saturday, Jan. 9, gawkers, malingerers, sentimentalists and the otherwise politically unimportant were herded into the muddy Brown Lot with their phone cameras and memories, far from the VIP tent below.

“They’re not going to be up here with the voters,” a man shouted, drawing a laugh.

How telling that the powerful Cuo-Honey alliance, entrusted with a $50 million makeover of the State Fairgrounds, couldn’t “grow” a single portable toilet for the hundreds of mourners.

Speaking of which, you don’t need to be a wiz to realize that at least some of those Grandstand seats — which meant so much to so many — could have been sold as mementos. Even I might have bought one. I didn’t come of age in Central New York, but I’m starting to understand something about the Grandstand: Not all the action happened on the stage or on the track.

“Do you have any fond memories of the Grandstand?” I asked City Court Judge James Cecile after the debris settled.

“Yes,” he replied. He refused to elaborate.

As it was, my only Grandstand experience consisted of people booing me from there. During a demolition derby at the fair in 2008, I missed the initial impact because I believed I was stuck in Park. In fact, all I needed to do was move this mechanical thingee called a shifter and put the car in Reverse.

Racing is complicated that way. Fans assumed I was sandbagging and, according to my wife and then-young children who were in the stands, much vitriol was hurled upon my person and my donated Ford. I heard none of it and finished in third place. It was the most fun I’ve had in my life.

Now, the only collisions we’ll see at the fair that don’t involve malfunctioning thrill rides will pit progress against politics. If you’re not sure who’s winning that race, ask yourself this: How often will you attend a concert at the new Lakeview Amphitheater, and then — for a night cap — walk a mile to watch a 1,300-pound Holstein relieve itself while you eat a corn dog?

Nor does it make sense, if the goal is to recreate the fair as a multipurpose, year-round venue that will attract people from throughout the Northeast and beyond (Hmmm, where have we heard that before?) to blast into oblivion Super DIRT Week, which drew 70,000 people and as much as $10 million annually into the local economy.

“In Arizona, a kid came up to me and said, ‘It sucks that they’re closing the track. I always wanted to go to Syracuse,” said Mike Mallet of dirttrackdigest.com as he waited for the end.

Let’s rewind that: “I always wanted to go to Syracuse.” Who ever says that other than top-ranked high school basketball recruits who can’t get into Duke?

I don’t have space to recount the nearly 40 years of memories shared with me in the Brown Lot. From Steve Martin when he was “wild and crazy” to Joie Chitwood careening around the mile oval on two wheels to the last concert by Patti LaBelle.

Perhaps the crowd’s sentiments were best captured by Janice Pliszczak (don’t ask). She worked in the box office for years and sometimes had to traverse the walkway behind the Grandstand. She soon learned that big Southern rock bands such as Lynryd Skynyrd attracted serious beer drinkers.

“I’d always carry an umbrella,” she said.

So should taxpayers.