Christopher Sinatra lives in Syracuse, NY, where he studies early American history at SUNY Oswego. He is working toward earning his MA in December ’15. Read Sinatra’s twice monthly blog, “Sleepwalking Through History,” on SyracuseNewTimes.com.

_________________________________

Resembling a bustling Coney Island or even an elegant Saratoga, the images of middle-class luxury on the shores of Onondaga Lake during its golden age are truly breathtaking. It’s as if a long-lost city were unearthed — an El Dorado or Arcadia. Well, perhaps more gilded age than golden age.

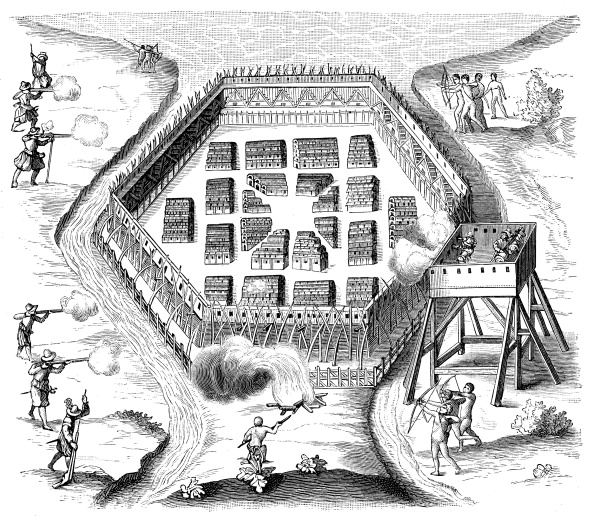

But further back, the landscape looked even more different. Four hundred years ago at the exact spot where Destiny USA now stands, there was an Onondaga Indian town. Records, however, don’t reveal how many houses there were inside. It was certainly not as large as the Huron town of Cahiague, which was said to have had 200 longhouses and between 3,000 and 6,000 people inside. Still, according to a contemporary illustration, it was quite impressive. It was surrounded by 30-foot-tall wooden fortress walls and topped by protective barriers, or parapets. Water coursed through the gutters to extinguish fires, should it threaten the wood.

Early in October in 1615, Samuel de Champlain appeared in Onondaga country, along with an interpreter and around a dozen French soldiers. Each wielded an arquebus — an ancestor of the rifle, which was not as accurate as a bow and arrow, but was faster and easier to use. While the Indians would become familiar with the exploding weapons soon enough, at the time, many were astounded at the weapon’s loud nose, which to them, resembled thunder.

Known to us today as the explorer who founded Quebec, Champlain was also an accomplished mapmaker, diplomat and artist; he provided the above-mentioned illustration of the town. His goal in North America was to found a New France, which would bring glory and riches to the mother country in the form of fish and furs. But he and his small contingent couldn’t do this alone. As the school-ditty goes, “they were already here.”

The Huron, Algonquin and Montagnais didn’t view Champlain merely as a threat. The French could also be used as allies against their powerful enemies to the south, the Iroquois, who had a habit of raiding their lucrative northern fur trade route. It was lucky for them that for all the resume-padding Champlain could have taken advantage of, he most often referred to himself as a soldier.

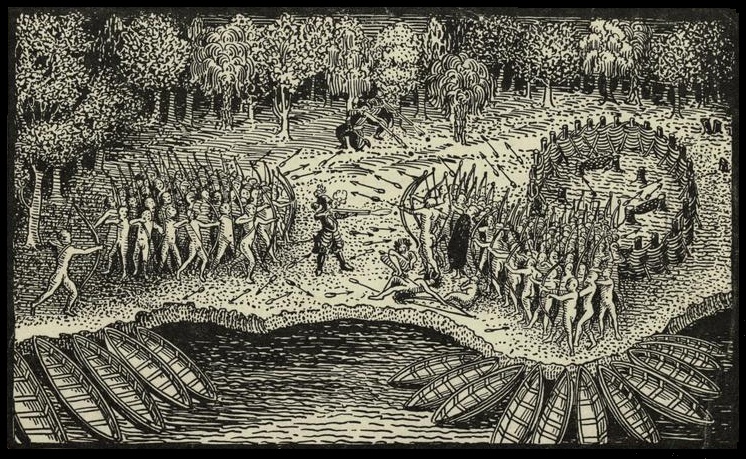

In 1609, the French and Indian force had attacked the Mohawks near Ticonderoga. The battle was nothing like what we are used to imagining Indian wars to look like. Clad in wooden armor, they used cotton-woven shields to deflect enemy arrows. The warriors approached each other in phalanx, or line formation, much like the Europeans did.

Photo provided by Wikimedia

But this time was different. To the surprise of the 200 Mohawk warriors, the Huron stepped aside to reveal Champlain dressed in armor and an elaborate feather-peaked helmet. When one or more of the Mohawk chiefs aimed their bows at Champlain, he fired his arquebus.

He shot four balls simultaneously, killing two of the three chiefs. Two French soldiers shot from under the cover of nearby trees and the third chief dropped, causing the Mohawk to flee. Perhaps simplifying things, warfare in North America would never be the same. The stealth and ambush strategy familiar from books and film was actually an adaptation to new circumstances. It would be foolish to rush in against the guns.

The French and Indian alliance attacked the Mohawk once more in 1610, and using the same strategy, they won. Yet, four years later, Champlain and around 500 Indian warriors marched toward “Iroquoia” again — this time to Onondaga Lake.

It took them more than a month to reach. Besides the unwieldiness of the large group, hunting for food was crucial and time-consuming. Creating their own supply line as they walked, they “advanced by short stages, hunting continually,” Champlain wrote. He was impressed at the Indians’ expertise in corralling deer into the water and killing them with large spears. The Indians were less than enthused when an arquebus accidentally fired and wounded a warrior. This required the French to give a gift of reparation.

After reaching Lake Ontario, the army island-hopped across by canoe and landed on the eastern shore of the lake. Now in enemy territory, they hid their vessels to enable a safe escape and over final four days trekked south toward the Onondaga by way of the path roughly followed today by Interstate 81. Along the way, Champlain admired the sandy shores, bountiful trees and the many fish provided by the Salmon River.

But as they neared their destination, an incident occurred which made it clear that this was not a sight-seeing expedition. The party came upon a small group of Onondaga — men, women and children — and took them prisoner. One of the northern Indians severed the finger of a female captive and an angry Champlain vainly objected that this “was not the act of a warrior.” A Jesuit priest would later write that this chastisement was not appreciated by another Indian, who promptly killed an infant to spite the French. Champlain was also informed that, despite his qualms, this was how they expected to be treated by their enemies.

As the large force reached the fortified town at the southern end of the lake, they expected to engage the enemy the same way that had succeeded against the Mohawk. The arquebusiers would shoot from the flanks as the Onondaga streamed out of the gates toward them. Unfortunately for Champlain’s plans, things went wrong from the start.

Photo provided by Wikimedia

Spotted before they were ready, it was the French and Indian army who were surprised, as they were attacked before they were in place. Small, unorganized skirmishes were the result and before long, the two sides regrouped to care for their wounded.

With the Onondaga behind such high walls, the circumstances now resembled a European battle, and accordingly, Champlain planned a siege. The Indians built a cavalier, or siege-engine, which towered over the fort walls and enabled them to re-capture high ground. They also constructed long wooden shields called mantalets, which would protect them against Onondaga arrows.

The French soldiers’ shot into the fort from their wooden platforms for a long time, perhaps even three hours. Secure under their mantalets, the attacking Indians tried to set fire to the fort. However, the wind was not in their favor, and water which fell from the fort’s gutters and doused the flames before any substantial damage was done.

Left to improvise, the attackers began to shoot arrows over the walls, but to no avail, and Champlain himself was hit in his knee and leg. He wrote that the Onondaga arrows “fell upon us like hail.” Soon, his allies began to refuse Champlain’s orders to continue the assault. “We are winning,” he insisted. They wanted to wait, however, until a group of Susquehannocks, who had promised to come and help defeat their mutual Iroquois enemies, had arrived.

The allied force waited for days, yet no one came. Finally, they retreated back up the path toward Lake Ontario and to their safely hidden canoes. Champlain would later write that the Indian warriors had not listened to his direction and, in any case, were not really soldiers. One wonders if they thought the man in the funny hat was a bit mad for not realizing that the battle was over and that they had not won. The fact that the French and northern Indians had defeated the Mohawks earlier must have made this especially frustrating, but in this case, earlier victory did not mean destiny.

It didn’t necessarily mean victory either, as many historians now argue. Not only did the attackers reach far into Onondaga country and inflict many casualties, but they suffered many less killed and wounded themselves. The warriors ferried their injured comrades away from the pursuing Onondaga in large baskets tied to their backs and no captives were taken.

Still, I would argue that the battle is an important part of the history of Syracuse for at least two reasons. As Champlain wrote, the goal of the mission was to take the fort, which the French and Indian alliance decidedly failed to do. For those who survived the onslaught, it was victory of a kind. As the historian Colin G. Calloway points out in his new book, The Victory With No Name: The Native American Defeat of the First American Army, defeat at the hands of Indians goes largely unrecognized today, even though it was considered vastly important at the time.

More recently, the debate over the cleanliness of Onondaga Lake asks us to question whether new technology is as dependable as we hope. As an Onondaga Nation youth group tried to remind us last week, the lake has been dredged, but its southern end is still too polluted for fishing or swimming. The clean-up, surely a great thing, can only be seen for now as — of a kind.