Chances are good that theater fans who know about epic productions such as Les Miserables and Miss Saigon also know about Richard Jay-Alexander, who ran producer Cameron Mackintosh’s North American operation for 10 years. Jay-Alexander was at Le Moyne College during a whirlwind stint that included seminars and master classes with budding theater students on topics such as the business of theater.

During a chat at the Coyne Center for the Performing Arts, the energetic showman dished on the celebrities he has collaborated with in recent years, including Bette Midler and Barbra Streisand. Yet he also poignantly addressed his childhood roots as a member of the Fernandez family in Solvay, home to his loving parents — who are now deceased — as well as his subsequent education at SUNY Oswego. His dad Frank Fernandez logged a 30-year career with Le Moyne’s accounting and business departments.

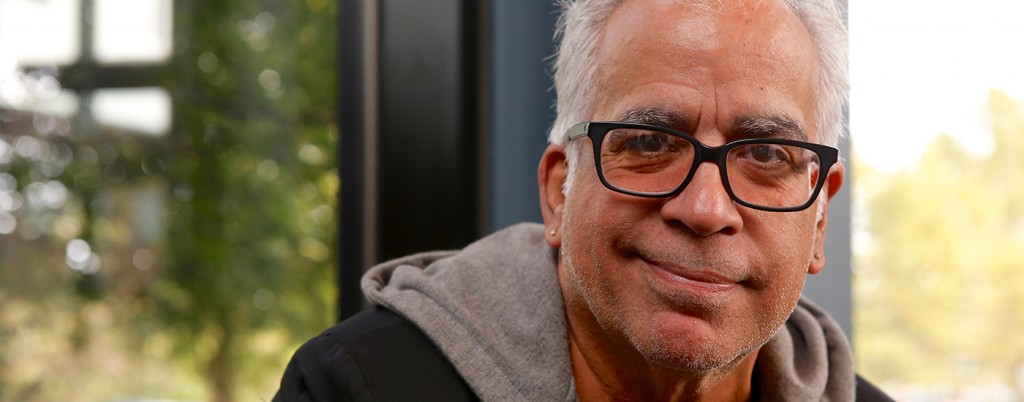

A telephone interview with Jay-Alexander, 62, at his Miami residence lasted nearly an hour, yet it seems unfair to boil the conversation down to a hit parade of sound bites. So what follows is a generous portion of his hometown memories, as well as his salad days as a Manhattan actor, with more to come in an upcoming issue.

By the way, he’s also an admirer of this publication, as well as its Syracuse Area Live Theater awards ceremony. “I’m such a Syracuse New Times fan,” he declared. “I was around during its inception — I was around in 1969, I’m sorry to say — and I always grab it at the airport, and that’s where I glean my info from.” End of plug.

Do you hand out advice to would-be performers?

When people go, “You know, my kid’s so talented,” or “Do you have any advice for my grandson,” Stuff like that. Most people that I know don’t give that kind of advice, because first of all you don’t know if they’re talented or not. Second of all, it’s an age of contests and people being so attracted to the red carpet or the Glee of it all. You know, it’s a calling and nothing will get in your way, but there is no easy way in. Now it’s even weirder, with the Internet and YouTube, and so you really have to find your place. But I still believe in training, and you also have to grow up; that’s what those four years of school will do. Otherwise, show business can damage you.

Michael Davis Photo | Syracuse New Times

Also, when my dad taught at Le Moyne, there was not a theater department when I was growing up, so this is a dream come true for him. He passed away a little over a year ago (at age 95), and he would have been so happy to see me speaking at Le Moyne. My father had a private practice as a certified public accountant, and he was a professor who ran Le Moyne’s department of business administration.

He was a hands-on dad. He really believed in education, first and foremost. When I was crazed and wanted to move to New York City at age 18, he said, “You’re going to get an education.” And I was really not smart, because I was obsessed with show business. I failed algebra three times, and the teacher said, “You’re not applying yourself,” and I said, “What does this have to do with show business?” My dad would drive down to that school and he would hammer her: “Don’t you make fun of my son.”

I still don’t know whether I cheated or what, but I passed algebra and my dad called the vice chairman at the theater department at SUNY Oswego to come see me in my senior musical at Solvay High. They took me for one semester on my enthusiasm, because I was turned down by every college in the country. And then, of course, once you start studying Greek theater and music and piano and voice, I became mental and made the dean’s list and got scholarships and I got out of school in three years.

Also, I grew up in Solvay and I never met Jewish people (until I went to college). “What’s Rosh Hoshanah?” I asked. Or people smoking pot who came up from Long Island: “Oh, I could never do that because of my parents.” But you get a sense of community. I couldn’t have gone from Solvay to New York City; it would have eaten me up alive. So my dad was very, very wise and he took what he knew and applied it to me. A lot of people hate their parents and have unresolved issues, but that’s just not me.

What was it like growing up in Central New York?

Syracuse was idyllic for me; it was an adventure. When I was in high school, I was riding a bus downtown and working for The Me Nobody Knows at Salt City Playhouse. Syracuse Musical Theater, the Pompeian Players, people like (Salt City executive director) Joe Lotito: There was just so much theater, and they really formed me. Things like timing are what you learn in community theater, and I totally believe in it. That’s what I give my time to, and all that stuff about paying it forward and giving back, it all sounds nice and I’m not big on words like arcs and journeys. But you do understand that when you can actually help somebody, it’s not a false mission.

There are times when you get paid for a lecture series, and there are times when you commit and then you can’t be held hostage from the truth. It’s not like when you’re getting paid so you have to be nice and kind. It’s a tough business and it’s tougher now because you have so many people who want to do it. When I went to New York City there was hundreds of people (attempting to break into show biz). Now there are thousands and there’s not even room for stars to have shows on Broadway.

But I love it! The interesting thing about me is that I still love what I do and I’m not jaded. I definitely have opinions. Definitely. But I can back ’em up with years of experience. This fall marks my 40th year in the business, which is sort of astonishing. I just got a new assistant and we’ve been transferring my career from VHS tapes to DVDs, and I’m sitting there and getting dizzy while watching them.

You had some bit parts in big movies.

They were screening (film director Walter Hill’s 1979 action drama) The Warriors somewhere and I was in that movie, so everybody starts posting on Facebook (the movie’s popular line of dialogue), “Come out, come out and play.” I was in the Orphans gang and I used to come home to my apartment on 300 W. 55th St. in the morning after getting rolled through the mud in Central Park. But who knew it was going to be a cult movie.

I was in (director John Badham’s 1977 musical drama) Saturday Night Fever as a dancer for six weeks, and when we saw the screening we thought it was terrible. And also when we danced, we didn’t dance to the BeeGees’ tracks, we were dancing to tracks of beats because the score wasn’t done yet. We had no idea; we thought it was stupid. Going to the 2001 Odyssey disco and being picked up every morning at 57th and Seventh Avenue on a bus, and then the dry cleaning would come out of your pants because of the disco’s dry ice … the whole thing was fascinating, especially in hindsight.

I benefited hugely from the British invasion of theater, everything from Amadeus to Song and Dance to (Broadway producer) Cameron Mackintosh. I benefited greatly from the crossing of the pond by the Brits. I was lucky, but I was also talented. But back in college, if I never studied music, I never could have been a stage manager, or an assistant director on Song and Dance. I do have to pinch myself a little because it happened to me so it’s not boasting, but I just can’t believe everything that I’ve done. It’s ridiculous, it’s insane.

When I made my Broadway debut in 1979 in Zoot Suit, my parents came to the Winter Garden, where I saw my first Broadway show Mame and where Barbra Streisand did Funny Girl. And my parents said, “You can die now.” Of course they didn’t mean that, I was only 22 or 23. So you’re talking to someone whose dreams have come true and more.

I had a whole Barbra Streisand wall in my (Solvay) bedroom. It was like a playroom, and there were (images of) Bernadette Peters, Bette Midler, Lauren Bacall and Liza Minnelli. How was it possible that I would be working with these people? I’m from Solvay, where everybody made fun of me: “Oooh, little Dickie wants to be on Broadway.”

And I learned about musicals from, thank god, the Solvay Public Library. They would call me and say, “Dickie, we got a new cast album. It’s called Rainbow with Steve Lawrence and Eydie Gorme.” And I would run down to the library and slap on those big headphones. I know every word to every score because of the Solvay Library. Back in those days, cast albums told the story. You didn’t need the dialogue because the songs moved the action, and you imagined what the show looked like. Everyone had cast albums of Man of La Mancha or Mary Martin’s Sound of Music in their home.

My parents would go to see (Broadway shows) like South Pacific and my mother would say, “Dickie, it was so romantic and your father and I cried,” and I was hanging on their every word. And when I was 10, my dad started buying the Sunday New York Times and I would pore over the (theater) pages. It was beyond glamorous, and I knew there was a world outside of Syracuse and I had to face it.

As an educator, my dad recognized that you had to be passionate about something. I didn’t want to be an accountant or a lawyer or a doctor. My dad was a nervous wreck, so he applied his knowledge skills to my particular desires, but he wanted to make sure that I could make a living. When the money started flowing, he knew I was gonna be OK.